'My First Novel' editor Alan Watt aims to demystify the creative process

Loading...

In Stephen King’s classic horror novel “The Shining,” an aspiring writer named Jack Torrance holes up inside a hotel to write his debut novel. Things don’t turn out so well.

Not many authors end up criminally insane like Torrance, but writers the world over can to relate to the maddening inner solitude of hunching over a blank page. To outsiders, it’s a mysterious occupation.

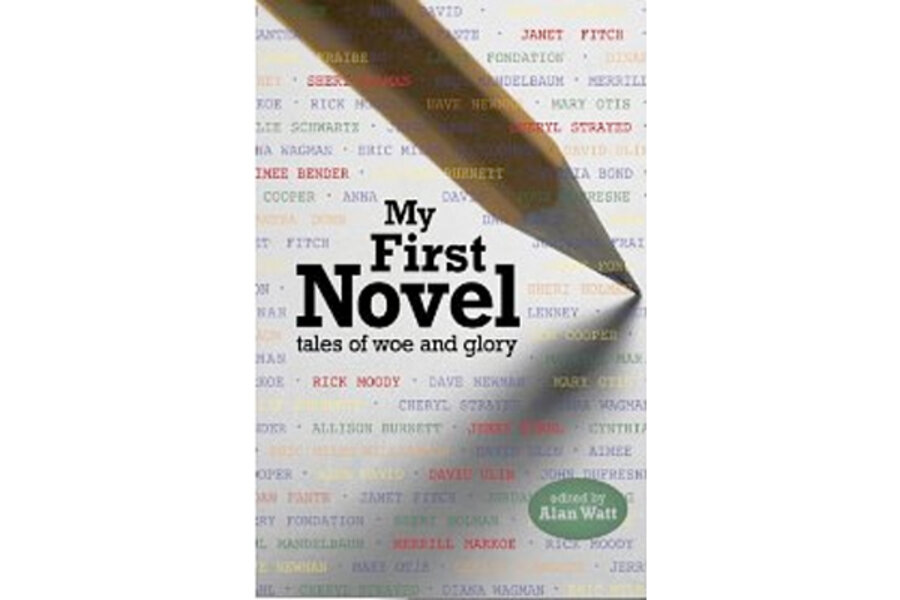

Alan Watt, the author “Diamond Dogs,” seeks to demystify the creative process in an anthology titled "My First Novel: Tales of Woe and Glory." To that end, he invited 25 published authors to share recollections about their formative writing experiences.

The notable essayists include Cheryl Strayed (“Wild”), Aimee Bender (“The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake”), Janet Fitch (“White Oleander”), and Rick Moody (“The Ice Storm”). In addition to editing the collection, Watt includes a fascinating account of how he wrote “Diamond Dogs.” Watt, a stand-up comic who once landed a cameo on “Seinfeld,” followed a similar modus operandi to the character in “The Shining.” During a six-week tour of comedy clubs, Watt locked himself in hotel rooms to write during daylight hours. Fortunately, the only person Watt killed during that time was a fictional character in “Diamond Dogs,” a story about a teenager who accidentally runs over a classmate and hides his body in the trunk of his car.

The success of “Diamond Dogs,” which sold to Little, Brown for over $500,000 and went on to win France’s Prix Printemps (Best Foreign Novel), allowed Watt to give up his night job. More importantly, the process of writing the book gave him a new insight on his fraught relationship with his father.

Almost all the authors in “My First Novel” underwent a transformational experience of some sort, many of them extraordinary. This isn't a "how to write" book as much as it is a collection of essays in which authors reveal how they overcome internal and external obstacles to complete their books.

Watt knows a thing or two about the trials and triumphs of writers. He’s written several bestselling books about how to write books, including “The 90 Day Novel,” and he also teaches in-person and telecourses through the LA Writers Lab, which he founded in 2002. The Monitor conducted an e-mail interview with Watt to ask him about his inspiration to compile “My First Novel” and what advice he’d offer to aspiring writers.

Q: How did you first get the idea for “My First Novel: Tales of Woe and Glory”?

A: The idea came to me while I was teaching. It is one thing to teach craft, but it’s another for the writer to understand that when getting published becomes the goal, the process gets corrupted. Of course it seems like it should be the goal, but really our goal is to make the story live. Publication is a byproduct of having created something other people want to read.

Q: You have the best-selling book on Amazon about how to write a novel and you teach in-person and teleconference workshops, too. Was “My First Novel” inspired as a supplementary guide to aspiring writers to provide them with inspiration and succor to get through writing their first novel?

A: Yes, that is exactly why I pursued this. I’ve been teaching the 90-Day Novel workshops for years, and the focus is purely on the craft of building a story, be it novel or memoir. But there is a misconception for many novice writers that until they are published, they are not allowed to think of themselves as writers, or that when the publishing gods finally anoint them, the writing will magically become easier. I wanted to put out a book of essays from published authors as a way of leveling the playing field by demystifying the process. In recounting their experience of creating their first book, the thing that stood out most is that this job requires hard work and persistence.

And there was the curiosity aspect as well. I wanted to know what other writers went through. We are an insular lot, and it was amazing to see how differently writers think about writing. As much as our desires are universal, our values vary wildly. I still have the romantic notion of artists being the moral force of society, but after reading this book, I realize that artists struggle with the same hang-ups as everyone else, we just have more free time to explore them.

Q: When you began to compile the essay submissions, did you notice common themes about the authors' experiences and some of the common personality traits of authors?

A: The common thread is that we all want to get published. We all want to be famous. We all want to be as widely read as Stephen King. I would say the single personality trait that stood out is obsession. We sit alone in a room imagining fictive worlds in microscopic detail. It’s a weird job, especially when no one is paying you, and when the likelihood of ever making more than minimum wage is a distant dream.

What compels us? Writing is a compulsion that I think will eventually be recognized as a disorder in the DSM. A woman once moved in with Charles Bukowski and asked him if her vacuuming would disrupt his writing. He said, “Nothing can disrupt it. For me, writing is a disease.”

The irony, at least for me, is that the disease saved my life.

Q: Which stories surprised you the most, and why?

A: Again, what surprised me was how hard every single one of them had to work in order to create that first book. I used to joke that I am the opposite of a prodigy, but one of the authors told me that other than Rimbaud and the Brontë sisters, the writing racket is filled with precious few prodigies. I wonder how many great writers out there quit three weeks before it all came together. The sentiment that writing is our salvation didn’t surprise me, but what did is that every writer expressed this in some way.

Q: The essays range from the recollections of Jerry Stahl, a homeless heroin addict-turned-author, to how Cynthia Bond spent 14 years writing her book amid a divorce, a miscarriage, a foreclosure, and years of working with at-risk youth. What can novice writers learn from “My First Novel” about the dedication and determination of writing a book?

A: The message I take away from it is that why we write is far more important than what we write. There are few experiences greater than the feeling of having expressed something in precisely the way you had imagined it, or the surprise that comes in saying something that you didn’t know you knew. Writing is magic. People are drawn to the act because it is a way of accessing the unconscious, of meeting God, of visiting the afterlife, of communing with the angels, and sometimes the devil.

It is thrilling and subversive. It is a drug. And once you take it, you are hooked for life, and if you ever quit, you never stop feeling guilty about it. The only cure is to write, and as hard as it is, it only feels worse when you don’t do it.

Q: Did any of the essays by the other novelists parallel your own experience in writing your debut, “Diamond Dogs,” in any way?

A: I related to Cynthia’s story in that the gestation period was long, although when I finally sat down to write it, it was like an exorcism. It came out fast and violent. Writing that book was like putting all of my forbidden thoughts down on paper as quickly as I could before I got called to the principal’s office.

Q: I think we've all met people who dream and talk about writing a book some day. What advice would you give those would-be writers about how to make it happen rather than continually putting it off?

A: There is no magic pill, and I don’t think there is anything you can say to get someone to write. I’ve been teaching writing for 15 years and a number of my students have gone on to successful careers as novelists, memoirists, and screenwriters – but I’ll be damned if I can predict who they will be. There are people with middling talent who work really hard and find their voice and have a career, while there are others who you would think are born writers and they can’t finish anything.

The irony of becoming an artist is that when you let go of the result, and lose yourself in the process, you are going to create something special. The other thing I would say, and it might sound esoteric, is that the universe does not want you to fail. When we commit to something with our whole heart, it is amazing how events conspire to bring that thing to life.

Q: All net proceeds from “My First Novel” are being donated to PEN Center USA’s Emerging Voices Fellowship. Tell us a bit about it.

A: PEN Center USA was founded in 1943 and is a non-profit organization committed to fostering a vital literary culture. They provide outreach programs for writers in the U.S. and support oppressed writers around the world through letter-writing campaigns among many other programs. The Emerging Voices Fellowship is a mentorship program that helps writers develop their craft.

Last year I taught a workshop for PEN called The Mark, which is a finishing school for a selected group of writers. That is where the idea for the book really took root. The 90-Day Novel workshop focuses solely on completing a first draft. We never talk about publication – in fact, that is verboten. But the PEN workshop was designed specifically to bring these writers to publication and I realized that there needed to be a paradigm shift. It made sense that I would put this book together as a way to support their cause.

Q: Will there be a sequel at some point – and, if so, do you have any writers on your wish list of contributors?

A: We just had a baby and bought a house and I need to get back to my own writing so that I can practice what I preach. If there is another book, it’ll be down the line. Of course, the list of authors is endless. I would love for Chad Harbach to write an essay. He has quite a story in bringing “The Art of Fielding” into the world. Michael Chabon, Alice Sebold, Russell Banks, Cormac McCarthy.

I would love to hear about Leonard Cohen’s experience in writing “Beautiful Losers.” A neighbor just told me he lives at the end of our block.

Q: You started a publishing company for literary fiction called Writers Tribe and you also have The 90 Day Novel press. What are some of the imminent books you’re about to publish?

A: We’re putting out a book called “The 90 Day Play” in 2014. It’s written by Linda Jenkins, who was the top playwright at Northwestern and was the teacher of John Logan – who won the Tony for “Red” – and Bruce Norris, who won the Pulitzer for “Clybourne Park.” It’s going to be a really good book. She teaches the 90 Day Play workshop for the LA Writers Lab.

Q: Who are some of the notable alumni who have taken courses through the LA Writers Lab?

A: Jennifer Scott wrote a book called “Lessons from Madame Chic” and she just last week sold her second book. Allen Zadoff, who wrote his first two novels in the workshop that were published by EgmontUSA. He just sold a thriller series to Little, Brown called “Boy Nobody.” Lucinda Clare wrote a bestseller in the workshop called “An English Psychic in Hollywood.”

Frank Wilderson, who won the American Book Award for his memoir “Incognegro,” wrote is first novel in the workshop. Jessica Sharzer has taken the screenplay workshop three times. In August, I helped her with her screenplay “Nerve,” which she sold to Lionsgate and then, immediately following that, helped her with her pilot “No Way Back” [which sold to ABC]. She’s getting very successful. She writes for “American Horror Story.” There’s a bunch more, including Jordanna Freiberg.

Q: What's your upcoming novel, “Days are Gone,” about?

A: It’s about a woman who leaves her marriage and ends up in a small town where she gets into a relationship with a guy who murdered his wife. It’s about forgiveness as a gateway to freedom. That’s all I can say.

Q: You're hoping to make “Diamond Dogs” into a movie, but it's taken a long and torturous road to get there. Tell us about the script's journey and where things stand now.

A: It’s been optioned to a producer every year for 13 years. There have been three scripts written, my own being the most recent, and hopefully the last.

I have witnessed first hand the vagaries of the film business. I have watched the movie come close to getting made so many times, and then get sidelined by ego, greed, control, perfectionism, sloth, and bankruptcy, but I continue to cash the checks. I think I’ve actually made more money not having the movie made. Whatever lawyer invented the term “film rights” ought to have a monument built for him.