'The Poisoner's Handbook' author Deborah Blum explores the history of forensic science

Loading...

Not too long ago, the keys to murder – undetected murder – lurked as close as the kitchen pantry.

Arsenic, cyanide, and strychnine were components of common household supplies and it wasn't uncommon to have them lying around. If not, a trip to the general store would produce them in a jiffy. Often colorless and tasteless, they'd be just the thing to add to a wastrel husband's oatmeal or an inconvenient grandmother's pudding.

Voilà: A perfect murder.

But the golden age of poisoning, which stretched from the 19th century into the 20th, came to an end thanks to scientists who set the standards for today's CSI crews.

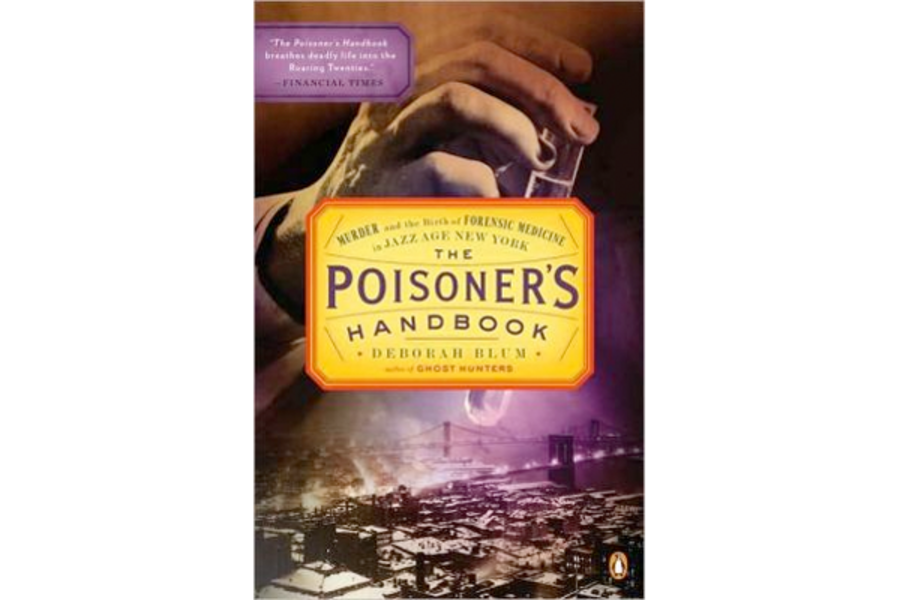

Science journalist Deborah Blum tracked the evolution of high-tech crime-fighting in 2010's best-selling The Poisoner's Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York. Tonight PBS's "American Experience" series will air a documentary based on her book.

I reached Blum this week at her home in frigid Wisconsin. We talked about the alleged femininity of poisoners, the use of killer poisons as an aid to inheritances, and the legacy of early forensic scientists.

I also mentioned the 70-degree-plus weather here in San Diego. "I'm hanging up now," she declared. Hope she doesn't send me any gifts from the pantry!

Q: Why was it so easy to poison people before the forensic scientists stepped in?

A: A lot of good poisons were easily available. You could go down to the corner store and get arsenic and cyanide was in all sorts of household products.

Strychnine was marketed as a pick-me-up tonic. And there wasn't a scientist in the known universe who could detect them in a body.

Q: If it was so easy to poison people and get away with it, why do you think there weren't even more murders?

Most murderers aren't poisoners; a huge number of murders aren't thought-out and planned. But poison murders are always premeditated. The murderers are cold, uniquely cold people: They plan and they plot and think about how they'll get away with it. We're lucky that there aren't more of them.

Q: Throughout history, poison has been described as a woman's weapon. What do you make of that?

A: Poison is an equalizer. Especially during the golden age of poisoning, they were in cosmetics, food preparations, kitchen poisons. Women had phenomenal access to poisonous things. And it's not a physically confrontational way to kill someone. You can even protect yourself and be somewhere else.

Women were really powerless – couldn't vote, couldn't own property – but they were queens of the kitchen. You almost always deliver poison in food and drink.

It's almost always in breakfast, like they're stewing about it overnight and in the morning it's in the porridge.

But the majority of poisoners are not women. The majority are men, about 60-40. The thing is that when women are picking a weapon to murder, they choose poison preferentially.

Q: Is poisoning seen as especially sneaky?

A: There's a line in "Game of Thrones" about how poison is one of the weapons of cowards, eunuchs, and women. It's weird: Let's diss women by saying they're inclined to poison.

Are women more conniving? Not to me. But I do understand that poisoners tend to be conniving.

Q: I think of poisoning as something that the wealthy do. Was that the reality?

A: Arsenic was known as "inheritor's powder." Poisoners are plotters and planners and they used poison as a shortcut to wealth.

Q: How did things change as forensic scientists developed ways to detect poison in the body?

Now you can nail these guys. They can't get away with it. That started changing everything as people started knowing they could get convicted.

Poison has never been the number one murder weapon, but you see a drop in that period in the number of poison homicides and you see serial poisoners really disappear. That just doesn't happen today with some exceptions like the Tylenol case.

Q: What did the evolution of forensic science in this period mean for crime-fighting?

A: It is much harder to get away with a crime. I look at poison, but you can make that case for many other crimes.

You go back to the 19th century and the police were not professional. During the period of Jack the Ripper, police were down there almost with street sweepers in terms of their place in society. Now forensic science is a profession.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.