Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr – teaming up on a court case?

If many Americans know about founding fathers Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr at all, it may be courtesy of a famous milk commercial from the early 1990s.

Yes, a bullet did indeed end the rivalry of these two men who helped the United States come to life. (And yes, peanut butter is better with milk.) But these two enemies – or frenemies, if you want to be all modern about it – had been partners before. They'd worked together to represent an accused murderer of a young woman in one of the most sensational criminal cases of the colonial era.

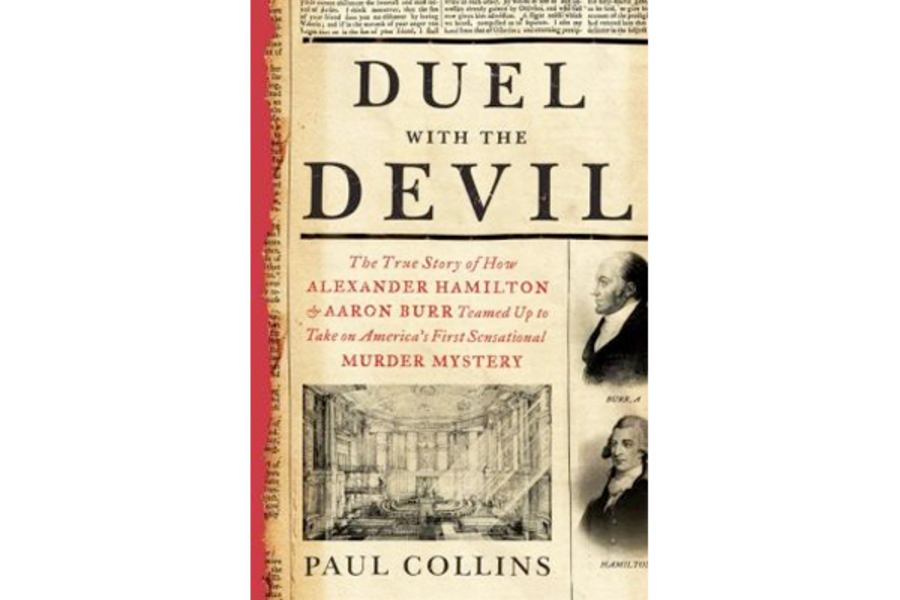

A sensational crime, that is, that's been utterly forgotten until now. Paul Collins, a Portland State University professor of English and one of America's premier historical true-crime writers, reopens the case in his new book Duel with the Devil: The True Story of How Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr Teamed Up to Take on America's First Sensational Murder Mystery".

Collins previously wrote several books, including 2011's "The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime that Scandalized a City and Sparked the Tabloid." In a Monitor review, I called it a page-turner enlivened by "a novelist's touch and an eye for the absurd."

There's more where that came from in "Duel with the Devil," a captivating blend of real-life police procedural and courthouse thriller with tons of vivid historical detail.

I reached Collins in Portland, Ore., and asked him to paint a picture of the political tensions of 1799, describe the tense relationship between these two men, and explain why a young woman's murder inflamed New York City.

Q: What drew you to this case?

The sheer unlikelihood of it. I came across this case in a collection of celebrated criminal trials that came out in 1900. I had never heard of the case and when they talked about Hamilton and Burr being the defense team, it sounded like a buddy movie. I couldn't believe it.

It was such an unlikely combination that I had to look it up.

Q: Tell us about the political world that Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr inhabited, not too long after the Revolutionary War. What sides existed, and which were they on?

A: They came from opposing political parties.

Hamilton was very much part of the Federalist Party, a political movement aligned with merchant class and bankers and pushing toward working more closely with Great Britain. That's where they saw the country's prosperity coming from.

Burr, who wound up being Jefferson's vice president, was more closely aligned with the rural, farming, agrarian economy, had more of a progressive view on things like women's rights and slavery, even though he had a slave.

Burr and other Republicans would claim that people like Hamilton wanted to turn the US into a British colony. Hamilton would fire back that Burr and the Republicans wanted to turn to the godless French.

Q: Hamilton's face is on the $10 bill. How was he connected to money?

He was really essential in setting up a stable financial system for the country. He did a great deal toward stabilizing the country fiscally.

Q: Hamilton and Burr clearly didn't like each other, but they'd still have meals together. Were they what we'd call frenemies today?

A: Yes.

They were not what you called close friends exactly, but they necessarily crossed each other's paths all the time. That's partly because of politics but also because they were both working lawyers. Even if they hadn't been involved in politics at all, they would have been running into each other.

Q: What did Hamilton think of Burr?

A: He described Burr as this unprincipled monster. Hamilton felt that Burr was very clever, very adept, clearly skilled at manipulating people and essentially had no morals, would do whatever he needed to do to get power.

He wasn't entirely wrong. Burr had a lot of admirable quantities, and he espoused a lot of positions that look good from a modern perspective. But he could be a pretty ruthless politician as well.

Q: What did Burr think of Hamilton?

A: We think of Burr now as the one who gunned down Hamilton. But in the way they actually carried themselves, it was Hamilton who tended to be a bit more intemperate in his speech and would get carried away with things.

Hamilton was easier for people to read. He was pretty plain about where his allegiances were. Burr was disturbingly quiet.

Q: Hamilton sounds like a bit of a heel, and he owed people money to boot. How did that happen?

A: While he was pretty brilliant about his fiscal policy, he was a disaster with his own. When he died, he died pretty deeply in debt: He'd carried on a bunch of romantic affairs that cost quite a bit of money.

What's interesting about both of them is that they're immensely talented and deeply flawed people, as many of the founding fathers seem to have been. They carried flaws that didn't overwhelm their abilities but did undermine them and made their lives more difficult than they needed to be.

Q: Other women were murdered in this era in New York City. What made this case so sensational?

A: The simplest way to put it is that it was a mystery.

With most cases of the other murders, it was fairly clear who did it. A number of times it was spouses. That was appalling to people, but that wasn't dramatic and it wasn't a surprise.

And then there was the way the body was discovered. It wasn't the ordinary madness of a domestic crime. It was found in the city well out in a meadow where she'd been hidden for weeks. It immediately had a mystery around it and it was shocking, too.

And she was young and beautiful, and the newspaper accounts all empathized that fact, adding this additional element of drama. It had all the hot buttons that tend to set people off.

Q: What's the legacy of this trial?

It was the first fully reported murder trial, where they had a full transcript where people could read for themselves actually what happened. It was a pretty important precedent for people to have access to those records.

It's also an impressive case because it presented a lot of modern techniques like laying out a timeline of how everyone would have been. Hamilton and Burr come out looking like the most modern people in the courtroom, really looking at evidence and trying to not get caught up in the crowd.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.