Trio of authors recall how they investigated dark family secrets

Emma Brockes's mother stood up against family abuse as a child in South Africa. Michael Hainey's father died mysteriously, and a code of silence obscured the truth for decades. A hitman robbed David Berg's brother of his life, leaving a legacy of guilt, fury, and regret.

These tales of mother, father, and brother are littered with secrets and shame. But in the hands of the survivors they've left behind, storytellers all, heartbreak gives way way to heft and meaning, healing, and humor.

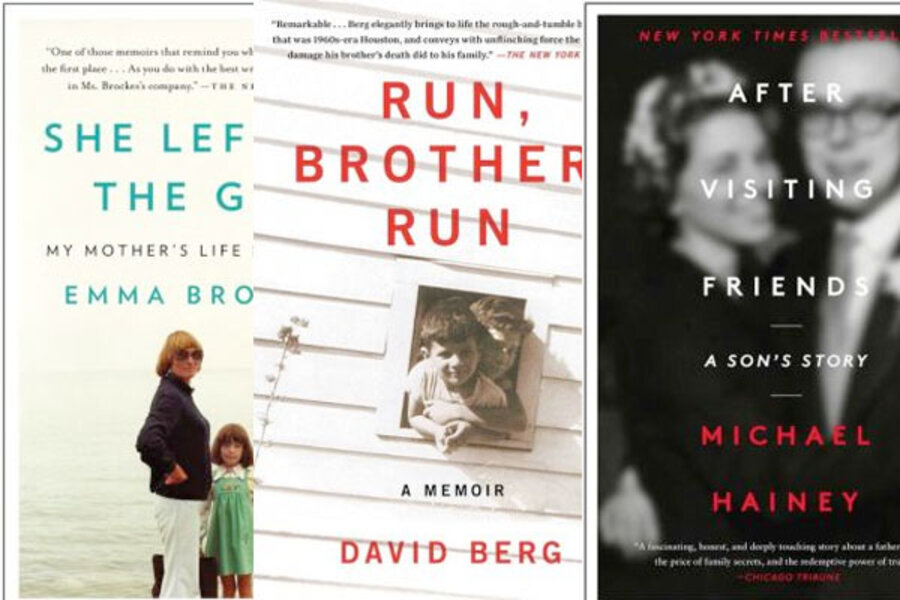

The family memoirs written by Brockes, Hainey and Berg – all published last year – are among the most remarkable books of the decade, full of deep voyages to times and places. Texas, South Africa, Chicago, Arkansas, England. The 1950s, the 1960s, and everything between then and now.

"Nobody gets through this life without tragedy," Berg says. "The question is: Does the tragedy define you? Or do you define the tragedy and get through it and wring all the self-pity out of it?"

I separately interviewed Hainey, Berg, and Brockes last year for author Q&A features in the Monitor. Late last month, I brought them together in person for a panel discussion at the annual conference of the American Society of Journalists & Authors. (As of July, I'll be the president of this non-profit association of independent writers.)

The title of the panel was "The Redemptive Power of Story." It turned out that the authors didn't necessarily find redemption, but they did work their way closer to peace, resolution and the truth.

Here are some excerpts from the panel discussion.

On hiding a deep family secret

Attorney David Berg's brother was murdered by a hit man in the 1960s. He felt guilt and regret ever since but found a way to deal with his pain by writing "Run, Brother, Run: A Memoir of a Murder in My Family."

Berg: "It's a story I needed to tell.

What triggered this for me was 'A River Runs Through It,' a novella that's very close to the murder of author Norman Maclean's brother over a gambling debt.

I'd never known anyone who had lost a brother. I went 40 years without talking about my brother's murder or talking about my brother. My children were left in the dark, and some of my friends didn't know I'd ever even had a brother.

I felt it was important that my children know not just the single thread of my brother's horrible end, but how our family life began in Arkansas, moving to Texas, and how there was that incredibly complex family dynamic led to Alan's murder.

My father had nothing to do with my brother's murder, but he pointed him in a direction in which he could never have missed that bullet."

On living in denial

Journalist Emma Brockes knew her late mother had endured intense horrors as a child in South Africa. But she didn't know the full story until she did the research that produced "She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me."

Brockes: "I'd resisted writing and talking about it for a very long time.

The events that constitute the material of my book were never spoken in my family. I had that taboo to deal with and sheepishness about writing this kind of memoir.

I'm a big fan of denial, and I think it gets a bad rap. If I could have been able to get away without doing this, I would have.

But there were two problems. First, if you know you're in denial, you're not in denial. You're faking it.

And secondly, when a parent dies, irrespective of how racy their background has been, your relationship with their history changes. You need to decide whether to take it on or let it vanish into oblivion."

On realizing they'd left themselves out of their books

Michael Hainey, a journalist at GQ Magazine, never knew why his father died suddenly in 1970. His dogged investigation reveals the truth in "After Visiting Friends: A Son's Story."

Hainey: "I was five years into it. I'd written a draft, and I took it to a friend. Three weeks later, I sat down with him, and he said, 'I have to tell you something: I don't see any of you in this book. You came back from all these reporting trips, you told me these amazing stories, but there's nothing of you.'

This light went off over my head. I was telling my father's story, and he was in the foreground, but I was in the background. It was both our stories."

Berg: "An editor told him that 'You're a storyteller, but this story is about you, too.' What's missing was how I was reacting to this story I'm telling."

On self-pity via memoir

Berg: "I didn't write it, honestly, to help others. I'm about the farthest thing from Dr. Phil, being a trial lawyer and a narcissist. I wrote it to give my brother a life, to explain what he was about.

I loathe self-pity and think that's at the heart of too many memoirs. What I tried to wring from this book was any semblance of self-pity. One of the reasons I didn't write the book for so long was that I didn't want to invoke 'I'm sorry.'"

On finding peace through memoir

Berg: "This book did more for me than all the therapy I ever had.

I didn't have trouble writing about my mother or father. They were dead. But I was very angry at them.

When I was done, I left almost all of that on the page. I've left most of my anger on those pages.

When you write memoir, it strips away all the years, all the layers of denial, layers of shame, and leaves you very vulnerable, and in touch with your feelings."

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.

Check out Randy Dotinga's previous interviews with Berg, Brockes, and Hainey.