John Wilkes Booth: history's most charming assassin?

Loading...

There may have never been a more charming assassin than John Wilkes Booth, who took the life of President Abraham Lincoln in a theater 150 years ago this week.

“He was a man with something to lose, not a born loser,” says Terry Alford, professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College. “He was somebody.”

As one of his era’s top actors, Booth had legions of fans, including at least two White House residents named Lincoln. His masculine energy and sexiness captivated women, and men found him to be a fine companion for evenings out on the town. When I asked if Booth had enemies, Alford – now his sole biographer – couldn’t think of one.

The reverse was hardly true. Booth hated the North with an uncommon rage, one that exploded in blood and ruined lives.

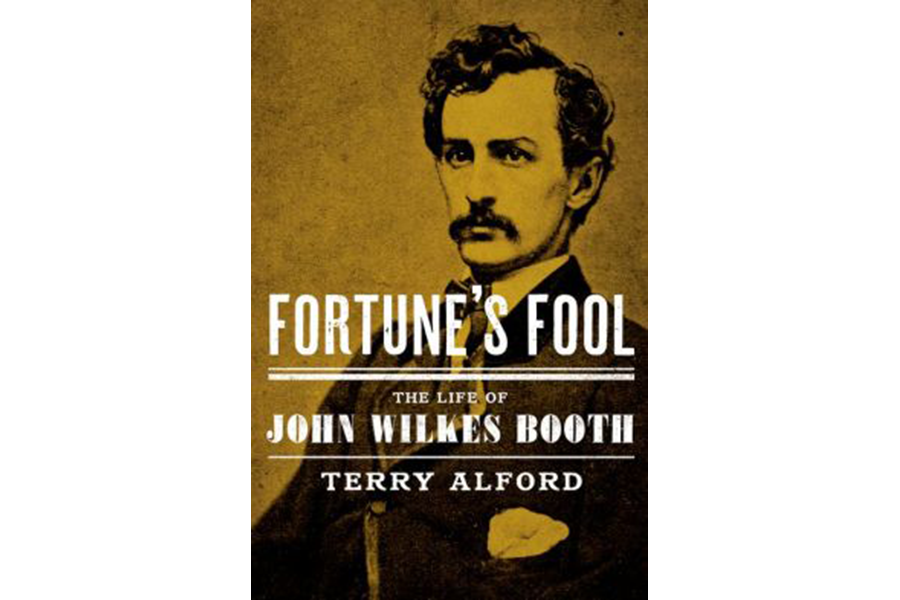

This assassin like no other deserves to be understood by history. What drove this beloved celebrity to murder? Alford seeks the answer in his extraordinary new book Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth.

We all know what happened on the night of April 14, 1865. Thanks to the gripping and deeply perceptive “Fortune’s Fool,” we know much more about why.

In our interview, I asked Alford to ponder what he learned about this extraordinary man’s life and his lust for revolution and revenge.

Q: What was John Wilkes Booth like in person?

He had drop-dead good looks, perfect teeth, great complexion. Physically, he was a marvel, a gym rat, an exercise fanatic.

A lot of people found him charming to be around with great personal appeal. He could be very sympathetic, he could put his face up next to yours and listen.

He was brave on occasion. When an actress’s dress caught fire, he put it out. And when a horse bolted with a young girl riding down the street, he ran the horse down and saved the girl.

It’s amazing how many friends he had, an army of friends of both sexes. He did a terrible thing, but as time passed and people felt safe to speak they mind, there’s a surprisingly positive amount of things said about him.

Q: You focus in the book on Booth’s incredible acting talents, which tend to be forgotten today. What was he like as a performer?

He was an exceptionally good actor. He excelled at physicality on stage – leaping, swordplay, dramatic conclusions. He’d seem a little bit over the top and melodramatic to us now, but that was pretty much what the audience wanted. He could also be tender and play parts like Romeo that required openness and sincerity.

I wonder if he would have burned out given his acting style. Once the curtain fell, he would lie on the floor for 5-10 minutes because he was so exhausted. I don’t know how he would have lasted or held up.

Q: What did he care about the most?

His main obsession was the opposite sex, and he had a two-volume little black book. He’d have his respectable upper-middle class girlfriends and romances, but their life was so restricted they had no idea of the world he lived in. He could be engaged to a high-born lady and be with prostitutes at the same time.

Q: What were the roots of his racism, which led him to deeply hate the North and Lincoln?

I thought a lot about that. He could be kind to individual African Americans, but the basic problem to him was that they didn’t belong in the United States. When the war came along, they were the most obvious beneficiaries, It was almost like for him, they couldn’t win freedom without him losing his. It wasn’t just that they would get something. He would lose something.

He identified all these changes with Lincoln. In fact, he seemed less focused on the war than Lincoln. I think he personalized Lincoln to represent everything bad that was happening around him.

Q: One of the amazing things about Booth, which is unique among assassins, is that he knew his victim, and his victim knew him and liked him. Booth was so famous that even Lincoln’s young son Tad was a fan. What did you learn about the connections between and his fan in the White House?

Lincoln had seen him act and applauded his efforts, and according to several people, Lincoln wanted to meet him. He was a star.

Q: As you write, shortly before the assassination, Booth tried to kidnap Lincoln, and he created public scenes by getting inappropriately close to the president. What was going on there?

At the end, Booth was starting to get desperate. It’s possible he could have shot Lincoln before he did.

Q: Why do you think he didn’t? Did he want to make sure he could escape?

As crazy as he became, he always showed a firm regard for not only doing his dirty work, but also getting out of it.

Q: Some people don’t realize that there was a wider assassination plot among Booth and his conspirators. The plot succeeded in killing Lincoln and severely wounding the secretary of state, although the vice president escaped unharmed. What did Booth think would happen next?

He realized he may gain some benefit by cutting the head of the government. If the South couldn’t kill the Northern army, why not kill the head?

Based on what he had to say, he hoped that the North might fall into revolution or confusion about who should govern, and it would be distracted enough for the South to win.

He knew this was desperate stuff, a major difference from plotting a kidnapping. He knew all that. Things that meant a lot to him like money, women, and family got swept aside by this fanaticism.

Q: If he’d ever faced trial, should Booth have gotten off on an insanity plea?

He’s not in crazy in the sense that we’re having lunch at the mall and we say, “Hey, look at that guy” because we’d both know something was wrong.

But he’s crazy in the sense of fanaticism: He’s perfectly OK on 9 out of 10 things, but don’t bring up the 10th thing. Fanaticism overwhelmed all of his good instincts – and he had many – and his good sense.

Q: How did you pick the book title “Fortune’s Fool,” which comes from Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet”?

It’s said when Romeo kills Juliet’s cousin and realizes what he done. Shakespeare was very invested in this idea of fate, that there are things impelling you forward that are out of your control.

Booth did say late in life to his mother that “I think there’s a hand on me that’s pushing me in a direction.” I think that’s exactly what was happening: He wasn’t in control of what he was doing. What he was doing in control of him. He was overwhelmed by his desire to help the South and for personal redemption for not having been a Confederate soldier.

Q: Booth lives for days after the assassination as he tries to escape, and he’s stunned by the universal horror at the assassination. How did he miss reality so completely?

He totally misread how people would see the assassination, and that makes you wonder how sane he is. But he had to be sane since he knew when to attack Lincoln and how to get out of Ford’s Theater.

He also said he wanted revenge for the South. He’d been exceedingly distressed by the Confederate surrender, and he’d seen prisoners being mistreated in the streets.

Revenge is not a very noble motive, but it’s a very human motive: “I’m hurting, and I want to share this hurt with you.” I think that was certainly in his mind.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.