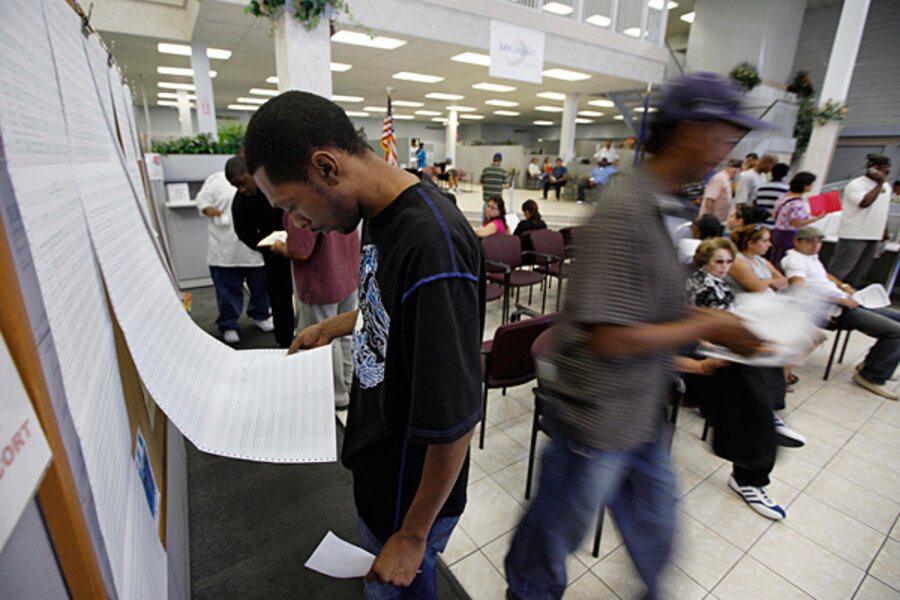

Unemployment rate up to 9.6 percent, but private sector gains jobs

Loading...

The number of jobs in the US economy fell by 54,000 in August, as declines in public-sector employment offset a small gain in private-sector jobs.

America's unemployment rate ticked up to 9.6 percent from 9.5 percent, in part because more people came back into the labor force to look for work.

Despite the economy's overall loss of jobs, these numbers from the Labor Department were better than many forecasters had expected. The jobs news included positive revisions to prior months' data. The economy lost 229,000 jobs in June and July combined, 123,000 fewer than had been reported previously.

Another positive sign: Although government employment has been declining because of the end of temporary census jobs, the private sector has posted positive job growth for eight straight months. The private sector is averaging 95,000 new jobs per month this year.

In August, the private-sector gains totaled 67,000 jobs.

All this prompted investors to greet the Friday jobs report as positive. The report buoyed hopes that the economy will escape a relapse into recession later this year.

But the question remains: With the economy posting growth for more than a year now, why isn't job growth stronger?

Even if the whole economy, including public and private sectors, were to post gains of 100,000 jobs per month, that's not enough to bring the unemployment rate down, many economists say. The reason is twofold: Population growth means new people are arriving in the labor force, and many older workers who have become discouraged may reenter the labor force over time.

An alternative unemployment rate, which includes discouraged Americans who have dropped out of the workforce and people who are working part time because they can't find full-time work, rose to 16.7 percent in August, its highest level since April.

One simple reason for slow job creation: Although the economy is growing, it isn't expanding very fast. Consumers, who are a key driver of the economy, are still digging out from the recession and trying to repair their finances after the housing bust.

In an economy with tepid growth, many employers can boost output by having their current workers put in longer hours, instead of hiring more people.

Add in uncertainty about the costs of health-care reform and about future federal tax policies, and many employers are hiring only if they absolutely have to.

Still, some recent news suggests that employers will have to do more hiring fairly soon.

In another Labor Department report this week, productivity in the private sector fell for the second quarter. That may be a sign that employers are reaching some limits in their efforts to do more with as few workers as possible.