A bull market plods into record-length territory. And now?

Loading...

On the surface, investing can seem a little weird. When the stock market is going gangbusters, savvy investors often sell their shares. When all is doom and gloom, they’re the ones who buy. Such contrarian thinking can be quite profitable. Had an investor bought US stocks on March 9, 2009, in the depths of the Great Recession, she would have seen her investment more than quadruple during what is now the longest bull market in modern history. But such a rational approach is also rare. Instead, most investors – even the professionals – tend to be too optimistic when times are good and too pessimistic when times are bad. These shifts in investor sentiment are not only harmful for individual portfolios, they also sway markets. A growing number of behavioral economists are trying to quantify and analyze these shifts in thought as a way to get a better handle on market risk. The authors of a new economics book, called “A Crisis of Beliefs,” put it this way: “The fragility of the financial system here comes entirely from beliefs.”

Why We Wrote This

Sentiment moves markets. That’s why those trying to get a bead on stock market stability amid a long-running boom seek to get a handle on investor expectations, which in turn drive investing behavior.

It’s been called the most hated bull market in history. Naysayers have criticized it for being too plodding, too weak.

But on Wednesday, Aug. 22, the run-up earned some newfound respect.

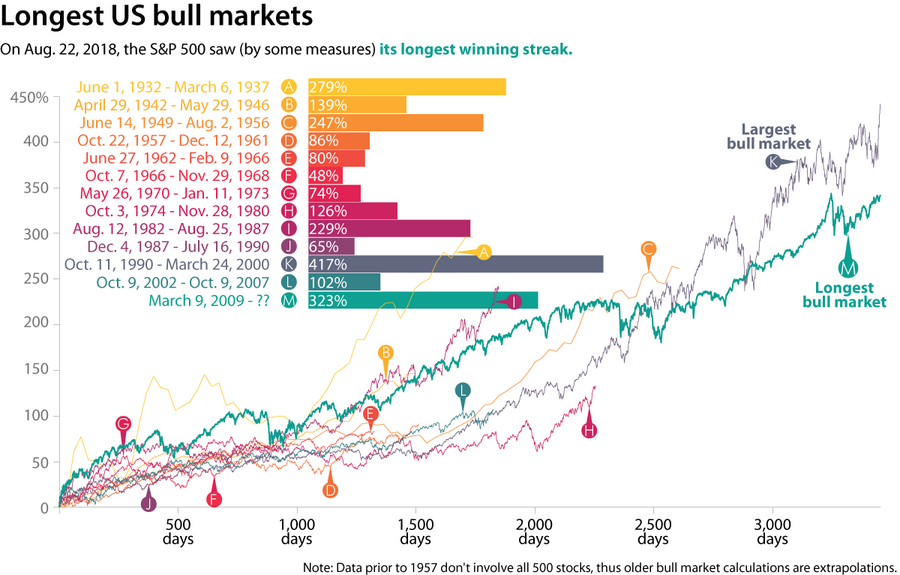

It is now the longest bull market in US stocks since modern recordkeeping began. And it is the second-biggest winning streak as well. (See chart.)

Why We Wrote This

Sentiment moves markets. That’s why those trying to get a bead on stock market stability amid a long-running boom seek to get a handle on investor expectations, which in turn drive investing behavior.

As a result, investor expectations – the majority thought patterns that underlie all markets – once again are turning positive. And a bull market that once looked fragile has gathered a new head of steam, adding to the wealth of shareowners, reinforcing the expansive confidence of businesses, bankers, and consumers, and lending a prosperous sheen to the tenure of President Trump just as it did for the Obama administration before him.

Here’s the problem: High expectations of good times are precisely the kind of danger signal that those good times may be about to end.

The correlations between investor sentiments and sea changes in the financial markets are messy – and hardly foolproof. By one measure, investor expectations were even more sky high in 2015, and yet the bull market has continued for another three years so far. And they lean heavily on how one defines bull and bear markets. (Not everyone believes this is the longest uptrend in modern history.) Nevertheless, increasingly skeptical of the long-held notion that investors act rationally, many economists are hard at work trying to figure out the connections between real-world investor expectations of future market performance and the sudden tipping points between bull and bear markets.

“There are many many people working on expectations now,” says Robin Greenwood, a behavioral economist at Harvard Business School. “That wasn’t true five years ago.”

It may sound perverse to say that confidence in good times leads to bad times and that expectations of bad times mean better times ahead. And after Wednesday, when the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index closed at 2,861.82, near a record high, it may seem downright contrarian.

Since sinking to 676.53 on March 9, 2009, in the depths of the Great Recession, the S&P has gone 3,453 days without a bear market (usually defined as a 20 percent plunge in stock prices). That eclipses by one day the 1990s boom. That runup remains the biggest bull market in history, with gains of 417 percent on the S&P, compared with the 323 percent gain so far of the current bull market.

But such cyclical thinking and contrarian logic permeate the investment world. “[B]e fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful,” investing superstar Warren Buffett famously said.

And various measures of investor sentiment reflect that contrarian thinking.

“High optimism is generally followed by underperforming markets,” says Charles Rotblut, editor of the AAII Journal, published by the American Association of Individual Investors, which tracks investor sentiment weekly. “Unusually low optimism tends to be followed by better than average markets.”

Where things get messy is if investors try to time when to get in and out of the market.

It’s not that the factors that eventually trigger a downturn are unknown. In the 1990s, for example, the sky-high valuations of the internet (or dotcom) stocks were widely acknowledged long before the bubble imploded. In 2008, the dangers of the runup in subprime mortgage debt was talked about.

The problem is that during good times investors underestimate the severity of those risks, argue Bocconi University (Italy) finance professor Nicola Gennaioli and Harvard Business School economist Andrei Shleifer in a new book, “A Crisis of Beliefs.”

Even professional investors take too exaggerated a view, the authors point out. In August 2005, for example, analysts at Lehman Brothers charted out five scenarios for home prices, including a “meltdown” in which they would decline by 5 percent for each of the following three years and then begin to rise again. The analysts assigned only a 5 percent probability to that scenario.

Instead, housing prices peaked less than a year later and dropped more than 30 percent. In 2008, Lehman collapsed, triggering an even more severe meltdown in the stock market.

“The fragility of the financial system here comes entirely from beliefs,” the authors write. Good economic news “leads investors to both overestimate average future conditions and to neglect the unrepresentative downside risk.” When good news stops coming, investors revise their expectations downward and, if the news is sufficiently bad, the sentiment tends to turn too pessimistic.

Currently, despite the S&P 500 being just a few points shy of its all-time high, investors don’t appear too overconfident. The share of bullish investors stands at 36.2 percent, according to the latest AAII reading, which is below the long-term average of 38.5 percent.

And the main threats facing the markets are well-known and not unlike those facing the 1990s boom: rising inflation, high stock valuations, and concerns about weakness in emerging markets, says Sara Johnson, executive director of global economics at IHS Markit, an economic research firm based in Andover, Mass.

And now that tax cuts have been priced into the market, “the opportunity for further gains has likely disappeared,” she says. “So the bottom line for corporate earnings is that margins could be squeezed and we’re likely to see either a leveling off of stock prices for the next several years or some correction.”

Unknown, of course, is whether inflation or some other unexpected development – a shift in oil prices, North Korean nuclear development, tariffs, a war in the Middle East – will trigger a downturn. And when investors’ perceptions shift again is anybody’s guess.