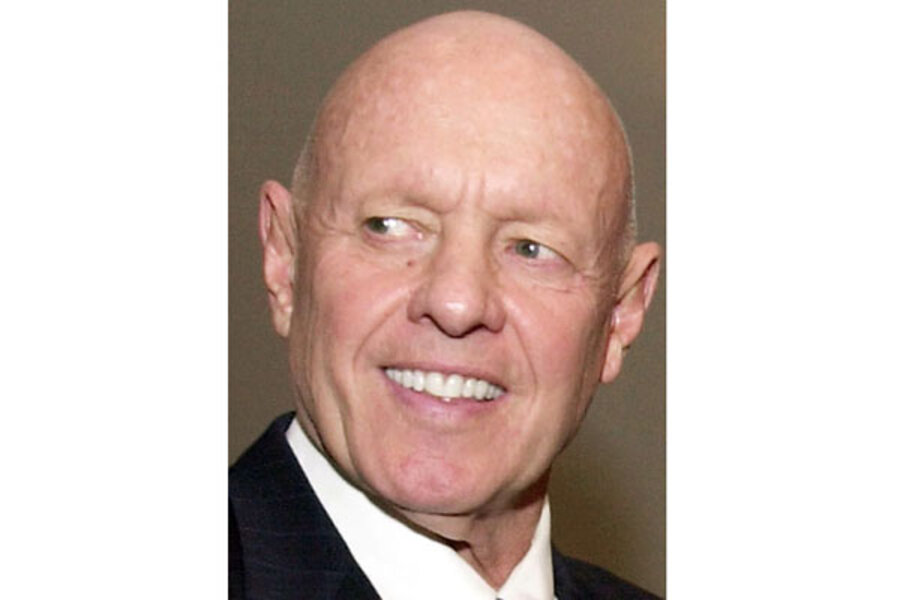

Stephen Covey, '7 Habits' author, dies at 79

Loading...

Stephen R. Covey, a former Brigham Young University business professor who blended personal self-help and management theory in a massive best-seller, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” died Monday at a hospital in Idaho Falls, Idaho. He was 79.

The cause was complications from injuries sustained in a bicycle accident, said Debra Lund, a spokeswoman for the Utah-based FranklinCovey leadership training and consulting company he co-founded.

In April, Covey lost control of his bike while riding down a hill in Provo, Utah. He was hospitalized for two months with a head injury, cracked ribs and a partly collapsed lung but “never fully recovered,” Lund said Monday.

Covey became a household name when “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People” was published in 1989. On best-seller lists for four years, it has sold in excess of 20 million copies in 40 languages and spawned a multimillion-dollar business empire that markets audiotapes, training seminars and organizing aids aimed at improving personal productivity and professional success.

“His timing was perfect. He really caught the wave ... as people were becoming increasingly fascinated with leadership. He addressed ordinary people’s desire to succeed through leadership and management,” said Barbara Kellerman, a lecturer on leadership at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Covey’s clients included three-quarters of Fortune 500 companies and scores of schools and government entities. He also trained three dozen heads of state, including the presidents of Colombia and South Korea and their cabinets. Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich were among his fans.

Part Peter Drucker and part Norman Vincent Peale, Covey summed up his philosophy in seven “unchanging principles” or habits that emphasize traits such as taking personal responsibility (“Be proactive”), having a road map or mission (“Begin with the end in mind”) and defining one’s priorities (“Put first things first”). His lectures were peppered with terms such as “synergy” and “paradigm shift,” but he also urged businesses to consider how employees feel.

“Coveyism is total quality management for the character, re-engineering for the soul — a tempting product in an age when the organizational versions of these disciplines have often pushed employee morale to rock bottom,” the Economist wrote in 1996.

“We believe that organizational behavior is individual behavior collectivized,” Covey told Fortune magazine in 1994.

Covey said the idea for “7 Habits” came partly from Drucker, the management guru who claimed that “effectiveness is a habit.” He agreed with his critics that his principles were gleaned from many sources, including the major world religions and classic psychology and philosophy. Some critics said Covey’s Mormon beliefs were a particularly strong influence.

Born in Salt Lake City on Oct. 24, 1932, he grew up on a farm just outside town. During his teens he developed a bone condition that forced him to give up sports and focus on academics. He often credited his parents with instilling a positive attitude in him — especially his mother, who would stand over his bed and tell him, “You can do anything you want.”

At 16 he entered the University of Utah, earning a degree in business administration in 1952. Five years later he received an MBA from Harvard.

Covey went on Mormon missions in England and Ireland. Part of his work involved training provincial heads of the church across Britain, an experience that altered his parents’ plans for him to take over the family hotel business. “I got so turned on by the idea of training leaders that it became my whole life’s mission,” he told the Ottawa Citizen in 2004.

After he returned to Salt Lake City, he worked as an assistant to the president of Brigham Young University. In 1969 he began studying for a doctorate in business and education, writing his dissertation on American success literature since 1776. He earned his doctorate in 1976.

Covey is survived by his wife of 55 years, Sandra; daughters Cynthia Haller, Maria Cole, Catherine Sagers, Colleen Brown and Jenny Pitt; sons Stephen, Sean, David and Joshua; two sisters; a brother; 52 grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Covey taught at Brigham Young until 1983, when he left to establish the Covey Leadership Center in Provo. In 1997 the center merged with rival Franklin Quest to form FranklinCovey.

He wrote several other best-selling books, including “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families” (1997). In a chapter on family rituals, he gave an example of what happened when he spent too long on a business call.

As the minutes ticked by, one of his sons grew impatient and started spreading peanut butter on Covey’s bald head. Covey stayed on the phone, so his son added a layer of jam and a piece of bread. Covey kept calm, which enabled him to continue conducting business while indulging his son. The lesson, Covey said, was Habit No. 4: “Think win-win.”