Why Mississippi's voter ID law hurts the poor

Loading...

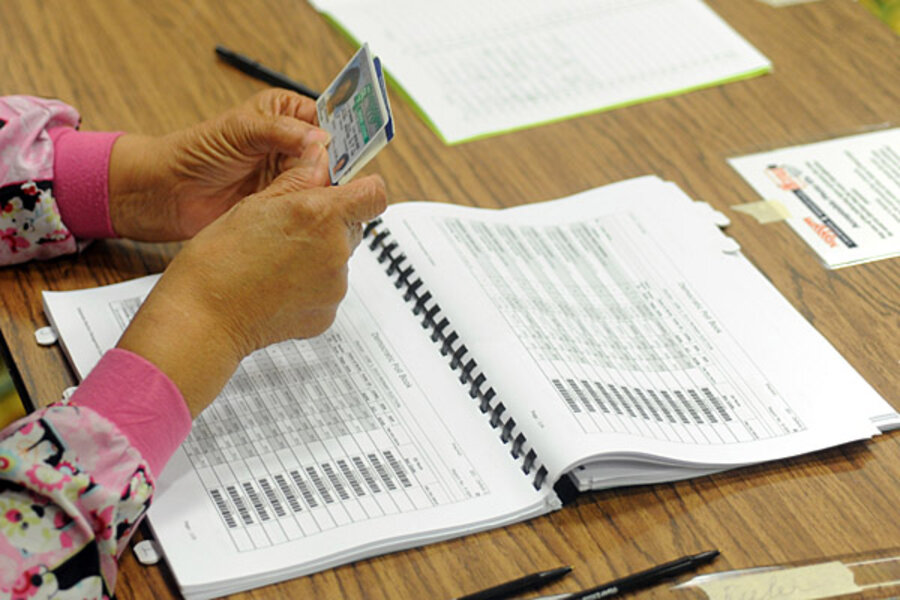

Mississippi used its new voter-identification law for the first time Tuesday — requiring voters to show a driver’s license or other government-issued photo ID at the polls.

The official reason given for the new law is alleged voter fraud, although the state hasn’t been able to provide any evidence that voter fraud is a problem.

The real reason for the law is to suppress the votes of the poor, especially African-Americans, some of whom won’t be able to afford the cost of a photo ID.

It’s a tragic irony that this law became effective almost exactly fifty years after three young civil rights workers — Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman – were tortured and murdered in Mississippi for trying to register African-Americans to vote.

They were killed outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, by a band of thugs that included the sheriff of Neshoba County. The state was deeply implicated: The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission had kept track of the three after they entered the state, and had passed on detailed information about them to the sheriff.

A year after the murders, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It was a direct response to the intransigence of Mississippi and other states with histories of racial discrimination, requiring them to get federal approval for any changes in their voting requirements — such as Mississippi’s new voter ID law.

But last June the Supreme Court’s five Republican appointees decided federal oversight was outmoded and unconstitutional, and that Congress had to set a new formula for deciding which states required federal review of voting law changes — thereby clearing the way for Mississippi’s new voter ID law.

Obviously, Congress hasn’t come up with a new formula because it’s gridlocked, and Republicans don’t want any federal review of state voting laws.

I knew Michael Schwerner. He was a kind and generous young man. And he meant a lot to me when I was growing up.

Now, fifty years after his brutal death and the deaths of his co-workers James Chaney and Andrew Goodman – fifty years after Freedom Summer — the state of Mississippi and the United States Supreme Court have turned back the clock.

Please urge your senators and representatives to pass a federal law that restores the Voting Rights Act, so Mississippi and other states with histories of repeated violations of voting rights cannot undo what Chaney, Goodman, Schwerner, and thousands of other brave Americans fought to achieve – equal voting rights.