Why tax breaks might not bring home prices down

Loading...

Tax preferences for housing are under fire, with mounting evidence that these preferences are inefficient, unequal, and too expensive to warrant a place in the tax code. Critics of proposed changes in the tax treatment of home ownership argue that these reforms would slash home prices at the very time they are showing signs of recovery. But in a new paper, I find that changes to the deductions for mortgage interest and property tax payments might not reduce prices much at all, and some reforms might even boost prices.

I estimate the impact on metropolitan housing prices of the higher tax rates imposed this year on high income households as well as three proposed tax changes: President Obama’s 28 percent limit on selected tax expenditures; eliminating deductions for mortgage interest and property taxes; and limiting the tax savings from the mortgage interest deduction to 20 percent while providing a flat credit for closing costs.

The president’s 28 percent limit on itemized deductions would barely move housing prices at all, causing them to fall just 0.3 percent. The higher top tax rates put in place in 2013, which drive up the value of deductions for housing for high-income taxpayers, are estimated to increase home prices by an even smaller margin.

By contrast, completely eliminating the mortgage interest and property tax deduction—a drastic change that probably would only happen if accompanied by a new tax preference for housing—would cause housing prices to fall by an average of 11.8 percent in the 23 cities studied. Estimated price declines would range from 10.3 percent in Seattle to 13.8 percent in Milwaukee.

Some proposed tax changes might even boost home prices. I estimate that limiting the mortgage interest deduction to 20 percent while offering a flat credit equal to two percent of a home’s value would raise prices an average of 3.0 percent. Price gains would vary from 1.5 percent in Pittsburgh to 4.6 percent in Portland.

Price effects could differ from my estimates, depending on how individual markets actually work. The effects could be lower, especially in the long-run, if the stock of owner-occupied housing adjusts to price changes—this can happen through either new construction or conversions between rentals and owner-occupied units. Or the price changes could be larger if metropolitan housing markets are driven by a marginal homebuyer in a high tax bracket, rather than being segmented across taxpayers in various tax brackets.

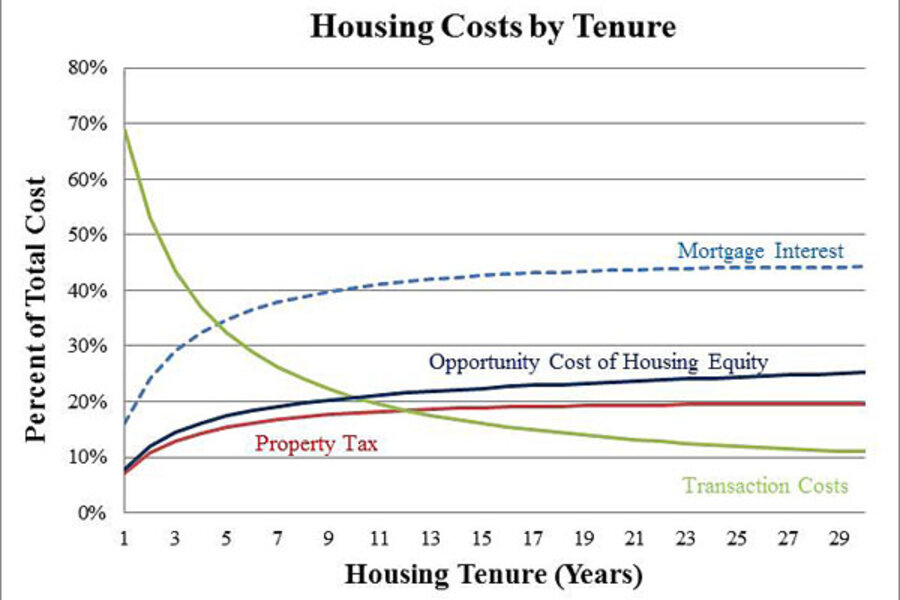

These findings diverge from prior studies, including one of my own, because they derive from a different way of thinking about housing investment. Earlier studies analyzed only the ongoing costs of homeownership—including mortgage interest, property taxes, and foregone return to housing equity. My approach adds transaction costs such as transfer taxes, title insurance, and realtor and broker fees to the costs of homeownership.

Transaction costs can dominate the cost of homeownership, especially for homes owned for short periods. For a home owned for less than four years, transaction costs are the largest expense, exceeding interest, property taxes, or foregone return to housing equity. For a home owned for 11 years—the median ownership across cities in the study—transactions costs still make up about one-fifth the total cost of homeownership (see chart).

The findings offer two important lessons for the tax expenditure debate. First, although completely eliminating the tax preferences for owner-occupied housing would reduce home prices substantially, curbing those preferences probably would not. Second, reform that limits deductions for mortgage interest while subsidizing the cost of housing transactions could actually raise home prices.

There are lots of barriers to a more efficient tax code. This research suggests that concern over lower home prices should not be one of them.