What does Detroit's bankruptcy mean for other cities?

Loading...

Detroit filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection yesterday, giving it the dubious distinction of being the largest municipal bankruptcy ever. By doing so, the city has put its future—and that of its citizens, employees, retirees, bondholders, and other creditors– in the hands of a federal judge. How did the Motor City get to this sad place, and what will it mean for other cities?

How did this happen?

Detroit has been in decline since the 1960s, when auto plants began to close and the city started hemorrhaging jobs. Its population declined from 2 million in 1950 to less than 700,000 today. But the city was slow to reduce its public payroll, and its retiree obligations have exploded. The city has been spending about $100 million more than it’s taken in over the last five years. It currently has an estimated $18.5 billion in long-term liabilities—nearly half of which are for retiree benefits ($3 billion for pensions and about $6 billion for health care and other benefits)

Was this bankruptcy inevitable?

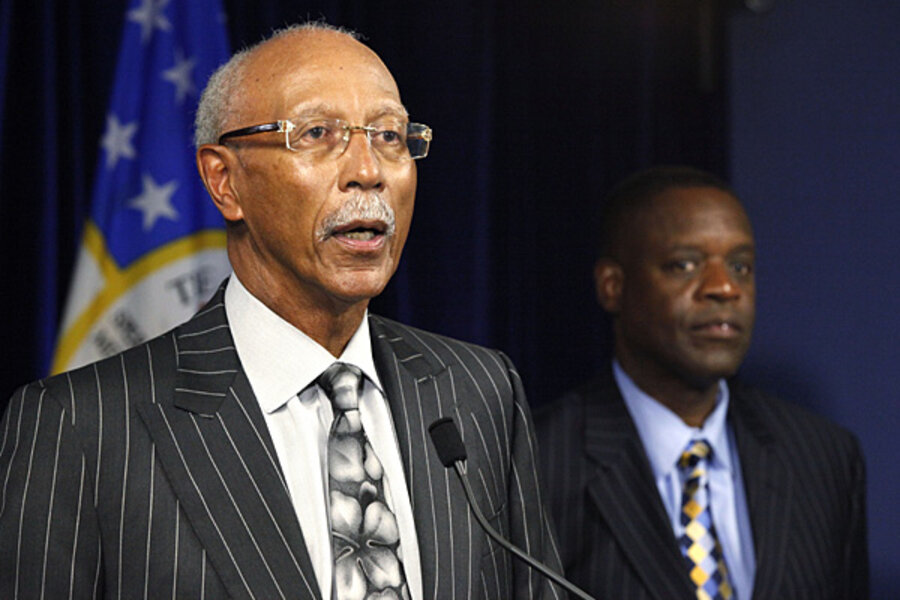

Probably. Last spring, the state appointed veteran bankruptcy lawyer Kevyn Orr to serve as the city’s emergency manager. But Orr was unable to convince creditors to work out the city’s obligations, and individual lawsuits have been piling up.

The crisis has been building for years. Not only is Detroit’s population shrinking, but those who stayed are older and poorer and thus need high levels of municipal services. The city struggled to provide those services while meeting prior obligations.

But by delaying the day of reckoning, it very likely made matters worse. Detroit borrowed to pay for both current operating costs and pension obligations. Government officials also increased retiree benefits when negotiating labor contracts for public employees, trading off future payments for current needs. They ignored an important rule of budgeting: When in a hole, first stop digging.

Will Detroit salvage its finances and move forward?

Bankruptcy is the right move for Detroit. It is the only forum where public sector unions, retirees, and debt holders can work out their competing demands. In the end, it is likely they all will have to face reductions in payments.

Despite the headlines, bankruptcy does not necessarily mean the city’s bonds will default. Indeed, Chapter 9 can be a mechanism for borrowers to avoid default. However, Detroit faces a series of stark choices. If bondholders take a haircut, the city’s cost of future debt will rise, limiting its ability to invest in a new Detroit. But if the bulk of the settlement falls on public employees and retirees, what will that do to the city’s ability to hire the police officers, firefighters, and teachers it needs to attract new residents?

In the end, it’s likely the state will have to step in to help make pension payments, guarantee future borrowing, or both. However, if its creditors are satisfied, Detroit can learn some lessons from New York and Washington, D.C.—two cities that went to the financial brink and ultimately thrived. Both recovered thanks to tough new financial controls, transparency, and hard choices.

Is this beginning of a new wave of municipal bankruptcies?

Probably not. Other Rust Belt cities face the same demographic and pension issues that hit Detroit. But because of state requirements, some, like New York, have kept up pension contributions while others, like Cincinnati and San Diego, have introduced reforms to try to stem growing obligations.

It’s also important to note that most jurisdictions that have declared bankruptcy or threatened to do so were responding to the fallout of specific ill-advised projects, not to the kind of existential threat that Detroit is confronting. For instance, Harrisburg, PA’s highly publicized troubles are largely the result of a money-losing municipal incinerator project. Fortunately, there are not a lot of Detroits out there.