Behind Qaddafi's death: demographics?

Loading...

The pictures emanating from Libya – young men cheering the death of Muammar Qaddafi and shooting their guns in the air – are gripping. They're also a little misleading.

Libya has not taken a dramatic step away from dictatorship because of a surge of young people agitating for change, but precisely because there are relatively fewer of them.

That, anyway, is the argument of some demographers, who assert that population shifts are a major force behind the so-called "Arab spring" that has brought change to Tunisia, Egypt, and now Libya.

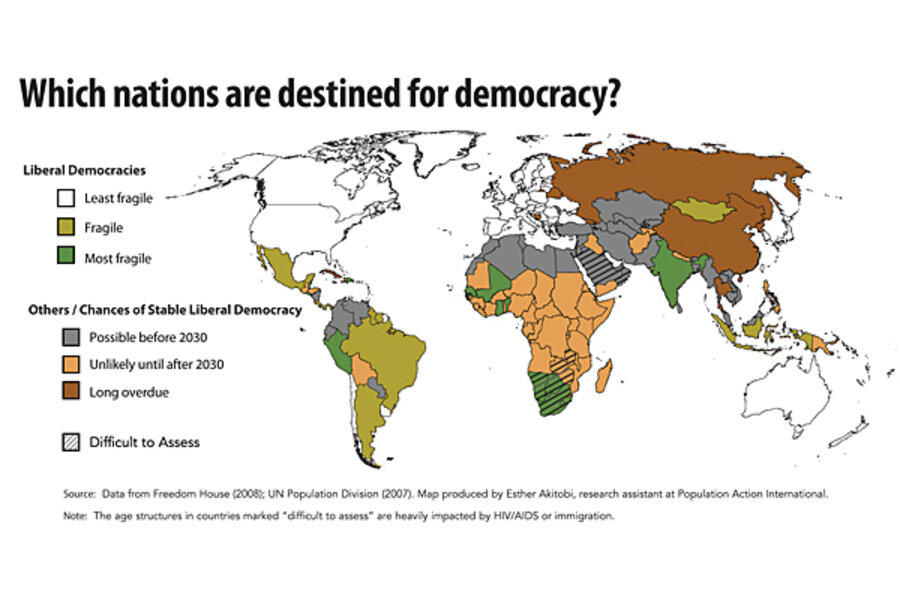

When demographer Richard Cincotta undertook three years ago to determine which nations had the best chance of becoming liberal democracies before 2030, he colored in all of North Africa, some of the Middle East, and on into central Asian countries such as Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (see map above).

IN PICTURES: Qaddafi's last stand

The reason: Fertility is falling, which is allowing these nations' youth bulges to mature. That may seem counterintuitive, but too many young people pushing for change causes other elements of society to lean toward stability. In 2008, Mr. Cincotta wrote:

"Countries with a large proportion of young adults ... are saddled with a social environment where the regime's legitimacy is strained and the political mobilization of young men is relatively easy. The resulting politics tend to be fractious and potentially violent. In this stage, regimes typically concentrate resources on preserving their position by limiting dissent and maintaining order, a focus that engenders the support of commercial elites and other propertied segments of society."

But when the bulge matures, nations are poised for dramatic economic gains, often called the "demographic dividend." With fewer children to support and the bulge now concentrated in the prime working years of 30 to 64, families save more, workers are more productive, and wages go up. That's what's happening in Asia and Latin America. It's now beginning to happen in the Arab world.

That's an ominous development for dictators, Cincotta wrote:

"With much of society's political volatility depleted, authoritarian executives tend to lose the support of the commercial elite, who find the regime's grip on communication and commerce economically stifling and privileges granted to family members and cronies of the political elite financially debilitating."

Voilà, the conditions are set for an Arab spring.

Of course, there are many examples of nations that enact democratic reforms before the youth bulge has matured, but often these democracies are fragile, Cincotta writes. "Latin American countries have tended, as a group, to embrace liberal democracy while hosting a large youth bulge, which may partly explain why 60 percent of these states have flip-flopped between a liberal democracy and a less democratic regime at least once since the early 1970s."

And there are no guarantees that nations poised to reap the demographic dividend will actually become liberal democracies. Think Putin's Russia, Lee Kwan Yew's Singapore, or Communist China.

Demographics "is overlaid with ethnic and tribal and religious differences," says Joseph Chamie, former director of the United Nations Population Division and now research director at the Center for Migration Studies in New York. Resource limitations, a lack of jobs, a poor work or savings ethic – all these can cause nations to miss the 35- to 40-year window of opportunity for dramatic change.

Will liberal democracies spring up in the rest of the Arab world? Cincotta is optimistic about the rest of North Africa as well as Lebanon. But he's not sure about the six Gulf states, because the high proportion of foreign workers there may well mask a more youthful indigenous population.

There are reasons for concern about the Middle East in the short term, Mr. Chamie agrees, but there's room for long-term optimism. "Demographics isn't destiny," he says. "But it's way ahead of anything [else] in second place."