Does the ad reference a longstanding racial stereotype historically associated with African-Americans? Does it state or suggest that President Obama is untrustworthy or prone toward criminality? Does it imply that he takes advantage of the system or is lazy?

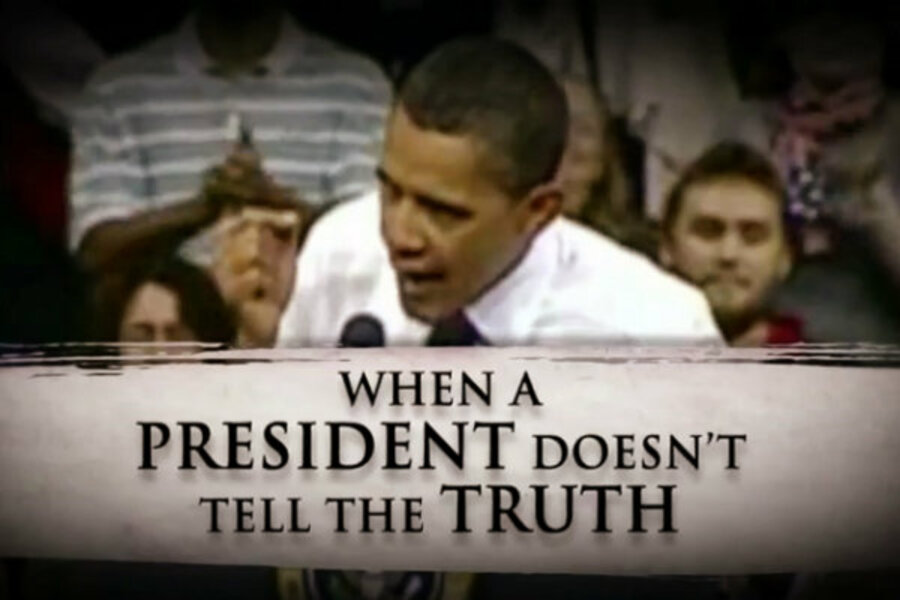

A recent ad from the Romney campaign, for instance, has the effect of presenting the untrustworthiness stereotype, calling Obama’s statements “not true,” and “misleading.” Then the ad goes a step beyond, by saying, “but that’s Barack Obama,” that is, the kind of person who misleads and says things that are not true.

The political ads we watched when compiling our index featured these kinds of racial stereotypes most frequently. But any stereotype reference increases the likelihood that the ad in question will draw out viewers’ negative associations with people of color. And while charges of criminality, untrustworthiness, and the like are standard attacks on white candidates, there is no stereotype associating whites, as a group, with criminality, untrustworthiness, freeloading, or laziness, so the potential effect is not the same.

But stereotype references in political ads can be subtle, and thus other additional features can make the stereotype more salient to viewers.