The new threat to freedom of expression

Loading...

| Washington

"In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world."

These are the first two freedoms of President Franklin Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" speech, which has special urgency today. The world economic crisis has naturally called attention to the last two freedoms he declared, freedom from want and from fear. But freedom of expression and religion got first billing for a reason. These two rights are absolutely fundamental to our humanity. And yet they've been under unceasing assault over the course of history.

These assaults continue today. On Friday, the UN Human Rights Council approved a resolution that calls on states to limit criticism of religions – specifically Islam. This is the tenth time such a resolution has passed at the UN's primary human rights body. Pakistan, on behalf of the Organization of the Islamic Conference, began introducing similar resolutions in 1999 arguing that Islam – the only religion specifically cited in the text – must be shielded from unfair associations with terrorism and human rights abuses.

These so-called "defamation of religions" resolutions also have a perfect record at the UN General Assembly, where the latest version passed in December. The resolutions contain some very appealing language, steeped in standard human rights values such as dialogue, harmony, and tolerance – all good things.

But don't be fooled; the resolutions only give clever lip service to these values. In reality they are calling for laws and actions that prohibit dialogue by declaring certain topics off limits for discussion, leading to intolerance of any view that some Muslims may find offensive. For instance, criticizing the practice of polygamy or the greater weight given to the testimony of men over women in sharia law would be forbidden. Such laws that prohibit blasphemy, defamation, or the defiling of Islam already exist in many of the countries that support the defamation of religions resolutions.

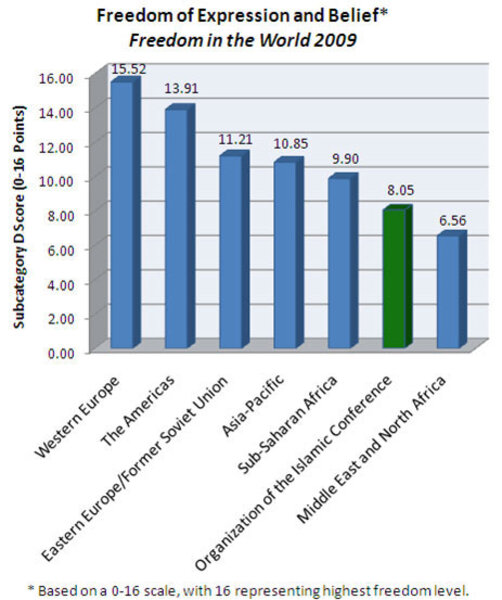

Who decides what views defame religion? Governments, of course. And the governments of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) have some of the worst records of respecting freedom of expression and belief in the world. Some of Freedom Houses's lowest-ranking countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iran, are frequent sponsors. Other countries with less-than-stellar human rights records, such as Belarus, Venezuela, and Russia, also sign on, seemingly for the purpose of opposing international norms of human rights rather than out of any real solidarity with OIC countries.

Of course, the very idea that you can defame a religion at all flies in the face of both fundamental rights of expression and belief. A religion, like all ideas and beliefs, must be open to debate, discussion, and even criticism. For this reason, religions themselves do not have rights. Rights belong exclusively to people.

Nonetheless, these resolutions present a win-win scenario for OIC countries. They serve to legitimize the repression of minority voices at home, while scoring points with religious leaders and Islamic fundamentalists by fueling views of an antagonistic and "Islamophobic" Western world. Extremists are thus tacitly encouraged to take action against any who dare to defame their religious sensibilities.

Salmon Rushdie, Flemming Rose, and Theo Van Gogh are just some of the better known individuals who have been attacked – and, in the case of Mr. Van Gogh, killed – for expressing views deemed defamatory. Thousands of lesser-known human rights activists, bloggers, academics, and journalists have been threatened, imprisoned, beaten, or killed for expressing their beliefs. Countless Muslims have been persecuted for voicing a brand of faith deemed unorthodox and therefore blasphemous or defamatory. It is impossible to know how many have not dared to raise their voices out of fear of retribution.

Moreover, the OIC is not satisfied with the legitimacy it gains from the passage of nonbinding UN resolutions. Supporters of the "defamation of religions" concept have insidiously begun using language from existing international human rights law, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to pervert international human rights norms.

One now rarely hears the term "defamation of religions" without the assertion that it leads to "incitement to hatred and violence," which is viewed as a legitimate restriction on freedom of expression under the ICCPR. Never mind that it isn't possible to defame an idea or belief. Never mind that human rights law was set up to protect the rights of human beings and not beliefs. This is the next battlefield at the UN and it is not one we should be prepared to lose.

Paula Schriefer is director of advocacy at Freedom House, a nonprofit that promotes democracy and freedom around the world.