Obama and Medvedev: Does Russia have the courage to change?

Loading...

| Vineyard Haven, Mass.

President Obama met with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev today. In their press conference, they talked about Afghanistan, an upcoming G-20 summit, and the World Trade Organization. What they should have discussed also is whether Moscow has the courage to lead Russia into a truly prosperous and democratic future.

Based on a recent meeting I had with Mr. Medvedev, I’m not sure it is.

In Moscow last month, I participated in a symposium on cultural values, cultural change, and economic development dedicated to the memory of Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington. I left with a strong sense that Russia is at a crossroads. Will it accept the mediocrity of continuing as a Second-World nation, or will it adopt the conditions to become a First-World power?

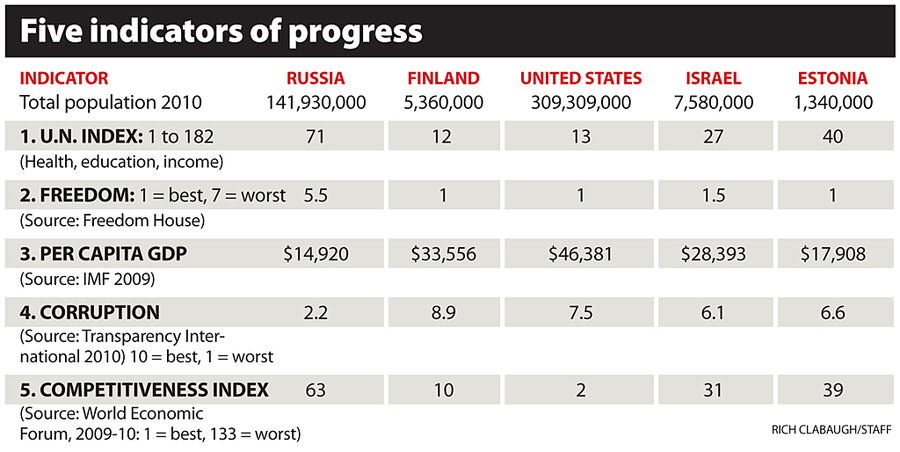

I essentially put that question directly to Medvedev at his residence. I distributed a chart about Russia (click on the graphic titled "Where Russia lags" at left) and expressed my belief that the indicators were rooted in cultural factors.

The table consists of five indicators of progress that cover political, social, and economic development. I had chosen the four countries to contrast with Russia for the following reasons:

•Finland, because it is among the Nordic countries, which, by these five indicators as well as many more that I have reviewed, are the champions of progress toward the goals established by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights: democratic governance, social justice, and an end to poverty.

•The USA, because it is generally regarded as the world’s leader and was Russia’s cold war superpower rival.

•Israel, because many Russians have migrated there in recent years.

•Estonia, because it was a Soviet Socialist Republic. Like Israel and Balkans development superstar Slovenia, Estonia has just been invited to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, largely a First World club. Estonia’s progress as an independent country evokes the Nordic countries, with which it has cultural connections, including the Lutheran religion.

Medvedev was not gratified by the table.

He commented first, that it was not comprehensive – there were other indicators where Russia would do better (I am not aware of any that would significantly alter the picture presented by the table); and second, that Russia’s identity was important to all Russians, and it shouldn’t have to change. I was tempted to reply that Russia’s “identity” might be the source of several obstacles to progress. But I concluded that I had expended my quota of controversy with the table.

Nobel Peace Prize winner and former Costa Rican President Oscar Arias followed with comments about his crusade to reduce spending on armaments, above all in the Third World. He pointed to Russia’s major role as an arms exporter. Once again, Medvedev appeared disquieted.

The collapse of communism has left Russia humiliated – it has lost its great power status and is on the sidelines watching as former ally and competitor China moves, apparently relentlessly, toward that status. Russia’s export profile looks like that of a Third World country, with the lion’s share of exports dependent on natural resource endowment, above all petroleum and natural gas. The country that beat the United States into space has been unable to produce an automobile of export quality – not to mention comparable shortfalls in creation of information technology.

In a period of national humiliation, one can well understand the intense concern expressed by the Russian leadership over the poor performance of Russian athletes in the recent Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

The low mark that Russia receives from Freedom House tends to confirm the frequent reports that one hears of abuse of power, corruption, absence of rule of law, and, in general, authoritarian administration of the country.

This impression is reinforced by the concentration of the media under the government. Nor can Russian democrats find any reassurance in the rumors of a Latin American-style switcheroo, with Vladimir Putin alternating – perhaps with Medvedev – between prime minister and president for the foreseeable future.

To be sure, the aura of authoritarianism that attaches to the current government is nowhere near as suffocating as was Soviet totalitarianism.

The extensive case study research of the Cultural Change Institute, which I direct at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, strongly suggests that when “identity” is a source of obstacles to progress, it must change if popular aspirations for progress are to be realized. Mikhail Gorbachev’s vision of a democratized, economically creative Russia is far more likely to bring Russia into First World abundance – and prestige – than leadership committed to recapturing Russia’s prestige through Second World authoritarianism.

Lawrence Harrison, director of the Cultural Change Institute at Tufts University's Fletcher School, is completing a new book, “Jews, Confucians, and Protestants: Cultural Capital, and the End of Multiculturalism.”