As world population heads toward a peak, Malthusian worries reemerge

Loading...

Food and people. Thomas Malthus posed them as two forces rarely in balance. Plentiful food encourages population growth. A booming population devours more food than can be produced.

Famine and other ugliness follow. Population crashes.

Students who learn of Malthus’s grim prediction usually take away two lessons. The first is the sharp contrast between arithmetic and geometric progression. Food supplies grow slowly, Malthus said. But consumers multiply like rabbits. A geometric progression outstrips an arithmetic one every time.

The second lesson is about why Malthus’s catastrophe hasn’t occurred. Most scholars think it is because the 19th-century Anglican parson didn’t have sufficient regard for technology and innovation. From the “green revolution” to global trade, from drip irrigation to entrepreneurial ingenuity, Homo sapiens learn and improve. We farm better, manage resources more carefully, and as education increases, birthrates fall.

A wise species – which is what “sapiens” means, after all – avoids a crash. That’s the story so far. But every rise in global food prices, every scene of malnutrition and starvation revives the old Malthusian fear. Malthus himself was careful not to predict when a judgment day would come. He simply noted a distinction between unlimited progress, of which he was skeptical, and “progress where the limit is merely undefined.” In other words, the jury may still be out.

Even if there hasn’t been one big catastrophe, there have been many regional ones since Malthus’s day. Famine in China, for instance, killed as many as 40 million people between 1958 and 1961. Bangladesh, Biafra, Ethiopia, and a dozen other regions suffered terrible food shortages in the 20th century. But these were not Malthusian events where a population outgrew its sustenance. Bad decisions – political incompetence, wars, brutal experiments such as Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward” – were to blame.

We have about 40 years before the jury renders its final verdict on Malthus. The population of the planet is currently 6.9 billion. By 2050, it will hit 9.2 billion, according to the US Census Bureau. Because of declining birthrates, population specialists believe that will be the peak. Whether you think more population growth is good or bad, that’s the predicted trajectory.

[Editor's note: The original version of this column said 9.2 million instead of billion.]

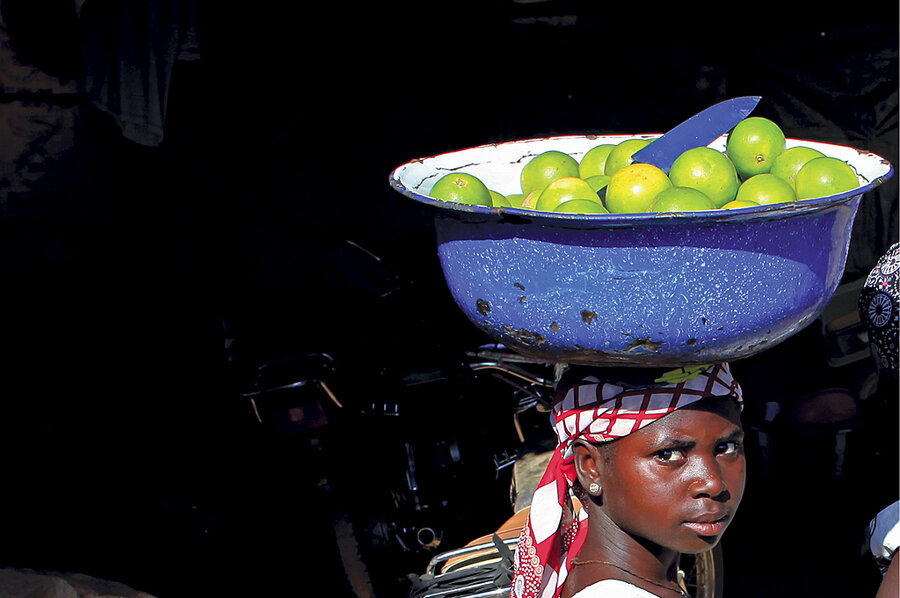

Can the planet carry another 2.3 billion people, the equivalent of another India and China? Where will the food come from? Agricultural specialists say that Africa, the subject of this week’s cover story, may be the next breadbasket. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization points to a vast savannah that spreads across 25 countries south of the Sahara as having the potential to transform the continent. The FAO calls this region, known as the Guinea Savannah, “Africa’s sleeping giant” and compares it to Brazil’s Cerrado region and northeast Thailand, both of which became important food producers over the past 30 years.

A special Monitor report describes how rich nations from China to Germany to Saudi Arabia are looking at the Guinea Savannah and other areas of Africa as a source of food and biofuel for their voracious populations. This is causing inevitable tensions, since African agriculture is made up of millions of small plots where families do subsistence farming.

Africans are rightly wary, considering their history. The 21st century could see a new form of colonial plantation displacing indigenous farms. Or, as happened in Brazil and Thailand, better farm practices could elevate African farmers so that they manage and benefit from the new global breadbasket.Our species can still prove Parson Malthus wrong. But it won’t just take wiser management of land, water, energy, and population. We’ll need a wiser form of humanity this time in Africa.

John Yemma is the editor of The Christian Science Monitor.