- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- ‘Divest from Israel’: Easy slogan, challenging task for universities

- Today’s news briefs

- Iran’s official line on exchange with Israel: Deterrence restored

- Trust in media has tanked. Are we entering a ‘post-news’ era?

- India tries to balance risks and rewards of AI

- A woman of Gaza on what Gaza’s women face

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A voice from Gaza

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Like many of you, I have been reading Ghada Abdulfattah’s searing accounts from Gaza. But there’s something about hearing her voice that drives it home in a different way.

Her “Why We Wrote This” podcast today is a lament, yes, for the Gaza she once knew. But it is also an act of defiance, a demand that humanity be seen and prevail.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Divest from Israel’: Easy slogan, challenging task for universities

Universities are starting to make deals with student groups that advocate divestment from Israel-linked corporations. Yet the current activism differs from the 1980s model of divestment from South Africa.

-

Jackie Valley Staff writer

“Disclose. Divest.”

The rallying cry, echoing on many large campuses in the United States in recent weeks, represents a powerful new voice in a two-decade international movement to protest Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories. As a purely economic lever, however, divestment appears likely to disappoint.

Such grassroots economic movements have a tenuous record of success. And economists say modern Israel represents a tougher target for protesters than South Africa’s apartheid government in the 1970s and ’80s or corporate fossil fuel polluters today.

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators have notched some gains at various American campuses in recent days, reaching compromises with university administrators that begin to address their concerns about disclosure of the school’s investment holdings. For U.S. universities, these are the first and easiest steps in a long road.

“These protesters are going to be really disappointed because I think they’re going to find that there’s really nothing much to divest from,” says Dany Bahar, an Israeli economics professor at Brown University. “Let’s invest instead of divest,” he adds, suggesting investment in Palestinian schools and infrastructure.

‘Divest from Israel’: Easy slogan, challenging task for universities

“Disclose. Divest.”

The rallying cry, echoing on many large campuses in the United States in recent weeks, represents a powerful new voice in a two-decade international movement to protest Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories through economic means. As a purely economic lever, however, divestment appears likely to disappoint.

Such grassroots economic movements have a tenuous record of success. And economists say modern Israel represents a tougher target for protesters than South Africa’s apartheid government in the 1970s and 1980s or corporate fossil fuel polluters today.

Still, pro-Palestinian demonstrators have notched some gains at various American campuses in recent days. They have reached compromises with university administrators that at least begin to address their concerns about disclosure of the school’s investment holdings. The deals may also offer a hopeful alternative to the violent clashes that have occurred at universities from Columbia University in New York to the University of California, Los Angeles.

“People are witnessing the horrors of war,” says Audie Klotz, professor of international relations at Syracuse University and author of a 1995 book on the struggle against apartheid. “They’re outraged, and they want to do something.”

The protests are a way to meet that urge, she adds.

Here at an encampment on the campus of the University of Vermont, amid signs reading “Divest Now” and chants of “UVM, it ain’t funny, show us where you hide our money,” James, a junior at the school, is feeling optimistic. (He declined to have his last name published because of privacy concerns.)

“Who knows how it all ends,” he says, motioning to the encampment behind him on the Burlington, Vermont, campus. “But this right here has given me so much hope and filled me with so much love about the collective power of students to meaningfully fight back against what is happening.”

A member of Students for Justice in Palestine, he says a group of students met earlier this week with university officials to request disclosure of the school’s investment and divestment from Israeli companies.

Hopes for a peaceful settlement to campus protests were raised Monday, when officials at Northwestern University struck a deal with protesting students and faculty. Protesters agreed to remove all but one tent pitched on the suburban Chicago campus in exchange for the reactivation of an advisory committee on university investment that will include students, faculty, and staff. The school also agreed to various steps to support Palestinian faculty and its Muslim students from throughout the Middle East.

On Tuesday, administrators and students at the Evergreen State College reached a similar agreement to remove their protest tents on the Olympia, Washington, campus in return for the school publicly endorsing a cease-fire in the Israel-Hamas war and considering divestment from companies profiting from Israel’s occupation of Palestinian land.

The same day, protesters at Brown University achieved a more far-reaching deal. Administrators agreed to meet this month with a student committee to reconsider a 2020 proposal that would drop from the university portfolio Boeing, Airbus, Raytheon, and eight other companies with ties to Israel’s defense establishment. Brown committed its corporate board to a vote on divestment in the fall. Rutgers and the University of Minnesota have also struck deals with protesting students.

Why divestment from Israel is difficult

For those advocating divestment, these are the first and easiest steps in what is likely to prove a long and difficult road, economists say. From there the issues get more complicated.

Divestment is a simple idea. Individuals or institutions rid their portfolios of holdings they believe are problematic, often for moral or ethical reasons. Health advocates might drop alcohol- or tobacco-related stocks. Pacifists would shun the defense sector. But when it comes to forcing political change in a nation, a big question is whom to target economically.

The Brown proposal has the advantage that it is narrowly focused on 11 stocks. Protesters at some other schools want the administration to divest from all Israeli companies.

“These protesters are going to be really disappointed because I think they’re going to find that there’s really nothing much to divest from,” says Dany Bahar, an Israeli economics professor at Brown. By his count, of the roughly 9,000 companies traded on the major U.S. stock exchanges, only about 120 are Israeli. Thus, universities are likely to hold few, if any, Israeli stocks directly, he adds.

Some protesters want universities to divest from all companies doing business in Israel, an even more difficult proposition given the global spread of many corporations.

Another complication: Whereas schools tended to own stocks in the 1970s and ’80s, when the South Africa divestment movement was active, many now own mutual funds. These allow universities to easily diversify their holdings and, in some cases, offer donors ways to support the school in line with their principles. For example, universities might pledge to those worried about climate change that their money would be invested in a fund designed to avoid fossil fuel companies.

Here in Burlington, for example, the University of Vermont released this week a list of nearly 90 mutual funds it’s invested in. Some of these funds hold dozens, even hundreds of companies. So if a Vanguard stock fund owns shares of Alphabet (Google’s parent company), which has come under fire for supplying the Israeli government with computing services, should the university divest from the entire fund?

Another big hurdle is legal. Thirty-eight states have laws, executive orders, or resolutions banning or discouraging economic boycotts against Israel, according to the American-Israel Cooperative Enterprise. That might discourage Brown, a private university, from taking an economic stand against Israel when Rhode Island law forbids companies that engage in economic warfare against Israel from doing business with the state. It may prove doubly difficult for public universities to divest in states with similar pro-Israel laws.

To the degree that universities make moves that placate protesters, they also may risk alienating other students, alumni, and donors – many of whom oppose the anti-Zionist views of groups like Students for Justice in Palestine. Already some donors have pulled back from universities like Harvard due to an alleged failure to clamp down on antisemitism.

Israel is not South Africa

Today’s Israel divestment movement contains echoes of the South Africa divestment movement. But there are key differences, too.

For one, the anti-apartheid protests did not spark the violent clashes with police and counterprotesters the way today’s demonstrations have. For another, the issues were more cut-and-dried four decades ago. Critics called the divestment movement unfeasible, but few supported the racist ideology of the white South African government. Today’s conflict is far more fraught, with pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli supporters both able to claim they are victims in the current war.

Another difference: Israel’s advanced, high-tech economy is far more resistant to boycotts and divestment than South Africa’s was. Over the past 40 years, Israel has built itself into a high-tech hub. It makes complex products that companies would find much harder to substitute than South Africa’s more basic products were. Israel’s high-tech sector saw a severe slump in foreign direct investment last year, but that was because proposed judicial reforms, which could weaken foreigners’ property rights, and the war have made outside investors hesitant to pour money in, says Assaf Razin, an economics professor at Tel Aviv University.

The impact of the divestment movement? “I don’t think it’s a serious threat,” he says.

Even the South Africa divestment movement was not nearly as consequential as many believe, says Professor Klotz of Syracuse. Far more important to apartheid’s overthrow, in her view, was that nation’s own internal protest movement and the international finance community’s reluctance to refinance South Africa’s debt.

“Let’s invest instead of divest,” argues Professor Bahar of Brown. “Let’s ask the universities to invest in [Palestinian] schools and infrastructure, in scholarships to students and faculty to come. ... Let’s be active in trying to do something that is going to take us closer to a future of two states – Israel, next to Palestine – living side by side in peace and security, and also in economic prosperity.”

Today’s news briefs

• Haiti prime minister switch: The majority of Haiti’s transitional council, which nominated an interim prime minister earlier this week, has walked back the decision, exposing internal tension within the group.

• U.K. elections: Britain’s governing Conservative Party is facing heavy losses as local election results pour in, strengthening expectations that the Labour Party is headed for power in an upcoming general election.

• Hamas peace talks: Hamas says it is sending a delegation to Egypt as soon as possible to continue talks in the latest sign of progress in the fragile cease-fire process.

• Severing ties with Israel: Turkey announces it is suspending all imports and exports to Israel; Colombia becomes the latest Latin American country to announce it will break diplomatic relations with Israel.

• Denmark abortion decision: Denmark’s government says it is relaxing its restrictions on abortion for the first time in 50 years to make it legal for women to terminate pregnancies up to the 18th week.

Iran’s official line on exchange with Israel: Deterrence restored

Iran’s attack on Israel, and the Israeli strike that preceded it, raised fears that the war in Gaza was poised to erupt into a regional conflict. Keeping sworn enemies from war requires delicate signaling and calculated deterrent acts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Nearly three weeks after Iran launched an unprecedented missile and drone barrage against Israel, Tehran’s official interpretation is that the strike succeeded, leading to the embrace of a more overt deterrent ability, analysts say.

Never mind that only a handful of the missiles detonated in Israel. Or that critics inside Iran, quickly hushed by judicial action, derided the strike.

Iran says its “epic victory” – avenging an Israeli attack that killed several Iranian generals in Syria – has created a “new calculus” for its adversaries. The barrage “left all the enemies bewildered about Iran’s deterrent power,” Iranian army commander Abdolrahim Mousavi said last week.

Still, Iran’s priorities will still include avoiding an all-out war with Israel and the United States, which could jeopardize regime stability, analysts say. But they now also include forging a new level of deterrence, as the long-held “rules of the game” have changed during the Israel-Hamas war.

Tehran felt compelled to “do something new, something unprecedented,” says Iran expert Adnan Tabatabai. “This attack had the purpose of Iran breaking out of previously known behavioral patterns, such as hiding behind plausible deniability, or keeping operations against Israel ambiguous.”

Iran’s official line on exchange with Israel: Deterrence restored

The horn of official triumphalism still sounds unabated in Iran, nearly three weeks after the Islamic Republic launched an unprecedented barrage, from Iranian soil, of more than 300 missiles and drones at Israel.

Yet triumphalism aside, Iran’s interpretation of events is key to understanding how it plans to capitalize on its recalibrated strategic position, and that of its regional “Axis of Resistance” alliance, including the embrace of a more overt deterrent ability, analysts say.

Never mind that only a handful of the missiles detonated in Israel – after Iran telegraphed its plans and desire not to escalate further. Or that critics inside Iran, who were quickly hushed by judicial action, derided the strikes, in one case calling them “theatrical” and saying they “only further fueled worries about Iran’s true defense power.”

Iranian officials nevertheless say they avenged an April 1 Israeli attack on an Iranian consulate building in Damascus, Syria, that killed several top Revolutionary Guard generals.

The officials said their strike, billed as Operation True Promise, demonstrated a flavor of their capabilities.

The barrage “left all the enemies bewildered about Iran’s deterrent power,” Maj. Gen. Abdolrahim Mousavi, commander of the Iranian army, said last week. “If need be, the Islamic Republic would hit any target in the world, any place it sees fit.”

In reply, Israel, under pressure from the United States not to escalate, launched a single strike deep inside Iran that reportedly evaded Iranian air defenses and destroyed an S-300 air defense system in Isfahan – a city home to a key Iranian nuclear facility.

Iran says its “epic victory” against Israel and Israel’s muted response have created a “new calculus” for its adversaries, after finally bringing a yearslong shadow war between Iran and Israel into the open.

Still, Iran’s priorities will include continuing to avoid an all-out war with Israel and the U.S., which could jeopardize regime stability or neuter allied regional militias, analysts say. But they will now also include forging a new level of deterrence with its archfoes, as the long-held “rules of the game” continue to fluctuate since the Israel-Hamas war erupted last October.

“Strong signal to the Israelis”

“This attack had the purpose of Iran breaking out of previously known behavioral patterns, such as hiding behind plausible deniability, or keeping operations against Israel ambiguous,” says Adnan Tabatabai, an Iran expert and founder of the Center for Applied Research and Partnership with the Orient, in Bonn, Germany.

With Israel in recent years stepping up targeting of Iranian military assets and personnel from Syria to Lebanon and Iraq – especially since last October – Tehran felt compelled to change the deterrence equation with Israel and “do something new, something unprecedented,” says Mr. Tabatabai, who travels frequently to Iran.

At the same time, he says, Iran deliberately sought to “do no serious harm,” and informed the U.S. “through two or three channels” what it would do, aware that most of its barrage would be intercepted.

The result, says Mr. Tabatabai, is that Iran, “in its own take of that back and forth between Israel and Iran, can say, ‘We gave a very strong signal to the Israelis about our capabilities and strong will to do something new – and a warning that next time we won’t warn you, may use even more missiles and drones, and may use [more advanced] systems that may not be intercepted so smoothly.’”

So Iran’s barrage – coupled with Israel’s subdued response, which was panned by one Iranian newspaper as “the clown’s performance” – “makes for a full victory speech for Iran, in terms of its own constituents,” says Mr. Tabatabai.

Senior officials have described the attack as a “limited warning” to Israel, to explain its apparent failure to produce widespread damage.

Indeed, Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei praised the “achievements” of the armed forces, but also said the “number of missiles fired and how many actually made it to their targets is trivial and of secondary value” because the attack “infuriated the other side.”

Altering assumptions

While the scale of Iran’s strike and the fact that it was launched from Iranian soil surprised many analysts – including, reportedly, Israeli officials – expectations had been building in Tehran to counter what was seen as increasingly brazen Israeli action.

“While not as many of their missiles got through, Iran did send a message and perhaps did force Israel and the U.S. to alter their assumptions and calculations,” says Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the Chatham House think tank in London.

“That in itself is important for [Iran’s] longer game and their broader strategic objectives,” says Dr. Vakil. “I think they were trying to force Israel to think twice, in order to stop the hemorrhaging around the region of their individuals and of their position.”

Iran may see as positive its accurate reading of the Biden administration’s lack of desire for the Israel-Hamas war to expand any further into a regional war, says Dr. Vakil.

“But they haven’t been able to fully deter or anticipate what Israel is going to do next, and I think they are calculating that they have a longer-term challenge on the horizon, with Hezbollah,” she says, noting that preservation of the Lebanese Shiite militia as a threat to Israel is critical to Iran’s own defense strategy.

“Ideally for Iran this [conflict] returns to the gray zone, and they can return to the status quo ante,” of applying pressure to Israel through proxy forces, says Dr. Vakil. “I don’t think they know if Israel is comfortable with that.”

Some in the Israeli government, in fact, are pushing for Israel to now tackle Iran-backed Hezbollah, which is far more capable than Hamas – with its arsenal estimated to include more than 150,000 rockets and missiles – and has engaged in increasing exchanges of fire on Israel’s northern border.

Yet according to the official narrative from Tehran, Israel would not dare to take on Hezbollah now.

Clampdown on critics

Meanwhile, Iranians who have raised questions about the cost and consequence of Iran’s barrage against Israel have been targeted by Revolutionary Guard social media channels, which have appealed to users to snitch on critics.

One high-profile example is Hossein Dehbashi, a well-known filmmaker, historian, and former journalist who posted praise of Iran’s change in strategy from “sitting back and tolerance, to one of direct retaliation.” But he also criticized the attack as “theatrical ... inefficient and unsuccessful.”

The next day he was summoned by Iran’s judiciary for “disturbing public psychological peace,” and a legal case was opened against him.

Such a clampdown may not be a surprise in a country that frequently limits reporting on dissent and protests.

“It’s something we have to expect in an environment that’s a war ... so there is no room for alternative narratives,” says Mr. Tabatabai. “Of course, the establishment is doing all it can to make sure the prerogative of interpretation remains uncontested in their hands.”

An Iranian researcher contributed to reporting for this story.

Trust in media has tanked. Are we entering a ‘post-news’ era?

Declining trust in the news media isn’t just about how polarization affects journalists and the public. It’s also about navigating a tsunami of digital content. Do people have room for news in their lives? How do they judge quality?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Trust in the news media has been falling for decades. Four in 10 Americans today say they have “no confidence” in the media’s news reporting.

This decline in trust may have major consequences. Democracies rely on informed voters. And those who engage with news typically engage with civic life as well. For the journalism industry, this trust gap has created a death spiral. Around 3,000 newspapers have closed since 2005.

In the fragmented digital realm, where opinion, commentary, and amateur video often muscle out evidence-based journalism, expertise no longer holds weight. Content providers know that shock and sensation drive engagement, which social media algorithms reinforce.

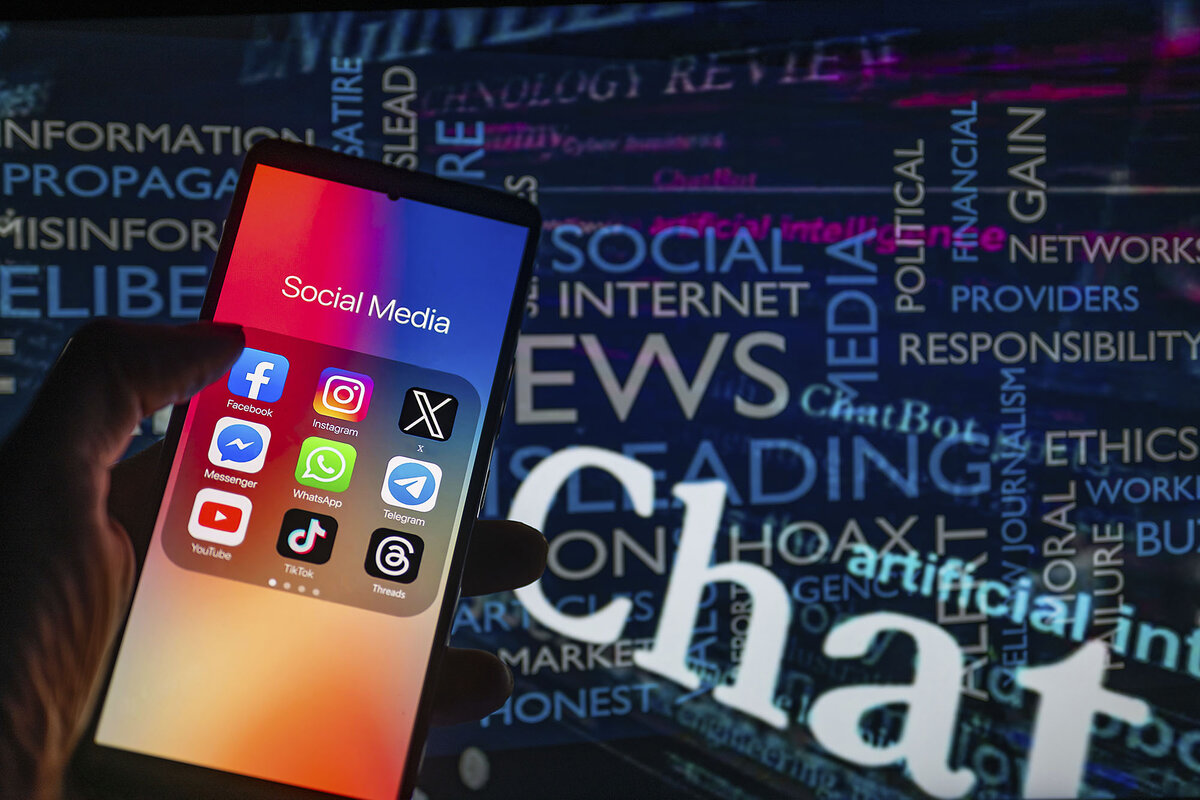

Lately, news influencers on Instagram and TikTok have been trying to reach younger audiences skeptical about traditional journalism.

One of them is Mosheh Oinounou, a former TV producer who runs a news operation called Mo News. Mr. Oinounou says he builds trust with followers by showing his work, crediting sources, and admitting the limits of his knowledge. He tells readers, “I don’t know what’s going to happen here, but here are a few ways to think about it.”

Trust in media has tanked. Are we entering a ‘post-news’ era?

Growing up in the pre-internet era, Mosheh Oinounou got his news the old-fashioned way.

“We’d wait in the morning for the [Chicago] Tribune to land on the driveway and see what happened in the world,” he says. There was also news on the radio and TV, where Mr. Oinounou built his career as a producer for CBS, Fox, and Bloomberg.

Today, that world of stable news diets – with its finite set of media sources that reached many U.S. households one way or another – has been swept away by an online tsunami of information. Half of U.S. adults now get their news, at least in part, from social media. That has sharply cut into revenues for newspapers and other publishers of news content, as digital platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Google have sucked up most of the advertising dollars that for decades had underwritten most journalism. In 2006, U.S. newspapers took in $49 billion in advertising revenues. By 2022, that amount had fallen to less than $10 billion.

These digital platforms are not only shaping how and when Americans get their news – they’re increasingly steering them away from it altogether, by deprioritizing news in their algorithmic feeds. Ironically, while today’s news consumers have greater access than ever before to a broad spectrum of information and viewpoints, much of it for free, many citizens are choosing a daily diet of podcasts, videos, and other digital content that circumvents more serious “hard news” altogether.

Some of today’s news-avoiders say it’s the media’s own fault. Many people no longer trust journalists to report the news accurately and fairly, says Benjamin Toff, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Minnesota and co-author of “Avoiding the News: Reluctant Audiences for Journalism.”

This distrust is shared even by some of those who still consume news regularly. In the United States, conservatives have long objected to what they say is a liberal bias in mainstream news organizations, a sentiment that has helped fuel the growth of a right-wing media ecosystem. Over the past decade, former President Donald Trump greatly accelerated this distrust by railing on the “fake news” media, often in an attempt to discredit critical headlines about him.

Still, arguments over media bias may miss the larger point – that a growing number of people simply are tuning out news entirely.

“There’s a larger segment of the public [that is] mostly just indifferent towards news,” says Professor Toff. “They will say in a survey that they are distrusting, but it’s not a deep-seated distrust. It’s actually more of a skepticism about the value and relevance of news to their lives.”

To be sure, many have long disparaged the news as depressing, boring, or irrelevant. Nevertheless, for much of the previous century, it worked its way into most Americans’ daily lives either via a newspaper that was primarily purchased for sports and weather or on a TV newscast that was left on between shows. Today, the internet and the rise of streaming make that kind of casual consumption –the news as ambient noise – far less likely.

“We used to rely on the newspaper industry introducing new facts into our media ecosystem. And it’s precisely that part of the infrastructure that’s disappearing,” says Victor Pickard, a professor of media policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

No longer a common set of facts

Overall trust in the news media has been falling for decades, along with a broader loss of trust in other public institutions. Four in 10 Americans today say they have “no confidence” in the media’s news reporting, while only 32% have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence. Back in 2003, when Gallup asked the same question, only 1 in 10 expressed “no confidence” while more than half expressed confidence.

This decline in trust in a free press and the demise of traditional news habits are likely to have major consequences. For the journalism industry, it’s created a kind of death spiral. Around 3,000 newspapers have closed since 2005; more than 200 counties across America now have no local news providers. As news outlets shutter or lay off reporters and editors in an effort to cut costs, it becomes even harder to win back the trust of their audiences.

But more broadly, the lack of shared news can lead to a citizenry no longer able to engage with one another based on a common set of facts and ideas. Democracies rely on informed voters with some sort of baseline knowledge on which to base their choices. Disengagement with news typically goes hand in hand with disengagement with politics, voting, and civic life.

News media travails: disruption, divides, and disinformation

Of course, the digital disruption of journalism doesn’t mean that all news reporting is about to vanish. A handful of large media organizations with relatively affluent subscribers may continue to survive, along with public broadcasters and national news networks tethered to (and subsidized by) entertainment divisions.

But their relative success may only deepen the divide between the small subset of voters who are well informed about public affairs and those on the outside looking in – or looking away.

“Not only is [fact-based news] becoming more scarce, as in there are fewer journalists, fewer news organizations out there, but also the reliable, high-quality news media is going behind paywalls,” says Professor Pickard, author of “Democracy Without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society.”

Cable news, the original disruptor for TV network news in its day, now serves a largely baby boomer audience: The median ages of viewers of Fox, CNN, and MSNBC are between 67 and 71.

In the fragmented digital realm, where opinion and amateur video often muscle out evidence-based journalism, expertise no longer holds weight, says Jeffrey Dvorkin, a former ombudsperson at NPR and author of “Trusting the News in a Digital Era.” Conspiracy theories thrive in such spaces, as does disinformation by Russia and other foreign powers.

This fragmentation has undercut the authority of traditional news sources. It “becomes a kind of rallying point for people to say, ‘Well, I don’t trust anybody. I don’t trust governments; I don’t trust the media; I don’t trust churches; I don’t trust universities. I trust what I feel is important to me,’” says Mr. Dvorkin. “They look for ideas and expressions that confirm their own feelings rather than inform them.”

Content providers know that shock and sensation drive engagement, which social media algorithms often reinforce. For example, video recommendations on TikTok have tended to showcase images from the war in Gaza that skew heavily to pro-Palestinian perspectives. Most of these videos don’t come from news organizations, which vet images and provide context, but are posted by activists, provocateurs, and influencers. Some have later been found to be fraudulent or misleading.

In a 2023 Pew Research Center poll, 32% of respondents ages 18-29 said they regularly get their news on TikTok, which favors short-form, user-generated videos.

Professor Toff led a three-year global research project on trust in news at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University. The researchers found that growing U.S. distrust in the news media was mirrored in other democracies, even as voters also worried about the veracity of social media content.

“A lot of people have internalized the notion that the smarter way to behave online is to be distrusting of everything you see because of just how varied the media environment is. And that, I think, can lead to the sort of generalized distrust that makes it harder to actually engage in the world,” says Professor Toff.

News organizations trying to attract younger audiences face a particularly difficult dilemma when it comes to social media. Allowing social media to disseminate their content means their stories are often presented alongside inflammatory and unreliable commentary, which can further degrade their brand. But irrelevance may be a worse outcome, particularly when more users are filtering out traditional news sources and are becoming impervious to the markers of reputable journalism.

The use of artificial intelligence to generate vast quantities of news content, as well as fake images and audio, adds to the challenge for independent, fact-based news outlets. Online audiences who already struggle with media literacy are likely to see an increase in AI-generated fake news, adding to general distrust towards all sources of news.

Startups that destress news

Lately, a crop of news influencers on platforms like Instagram and TikTok has been trying to reach younger audiences who are skeptical or indifferent toward traditional journalism. They aggregate and analyze news, downplay partisan spin, and use comments to respond to readers and to decide what topics to cover next.

One of them is Mr. Oinounou, the former TV producer. He began sharing news on Instagram during the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020. What started as a service for family and friends has become a fast-growing news operation, called Mo News, with premium subscriptions and newsletters. His Instagram account, which aggregates news from mainstream outlets under plain, descriptive headlines, has more than 400,000 followers. Most, he says, are women in their mid-30s.

“I think there’s an audience out there that continues to remain hungry for news. They’re just finding it in different ways,” he says. This audience “is coming to social media for their home advice, for their parenting advice – and for information and news related to a whole variety of subjects, and that includes political news.”

RocaNews, another startup that has around 1.5 million consumers of its bite-size news products, including a popular news-quiz app, also launched in 2020. Max Frost, a co-founder and president, says his Generation Z audience is looking for facts and context without political spin or sensationalism. “One of our missions is to destress the news. It raises the blood pressure to read the news, and it shouldn’t be that way,” he says.

Mr. Frost says many young social media users don’t see themselves reflected in stories from major news outlets, such as when they read upbeat coverage of an economy that feels stacked against them. “They don’t have money in the stock market. They don’t own property,” he says.

These blind spots cut across generations, says Tanzina Vega, the former host of “The Takeaway,” a national news show produced by WNYC. “There’s a huge class gap,” she says. “I don’t see a lot of media that’s for the working class.” With the journalism industry in such financial turmoil, more publishers are focused on wooing premium subscribers, who tend to be more affluent and politically engaged, which then shapes editorial priorities.

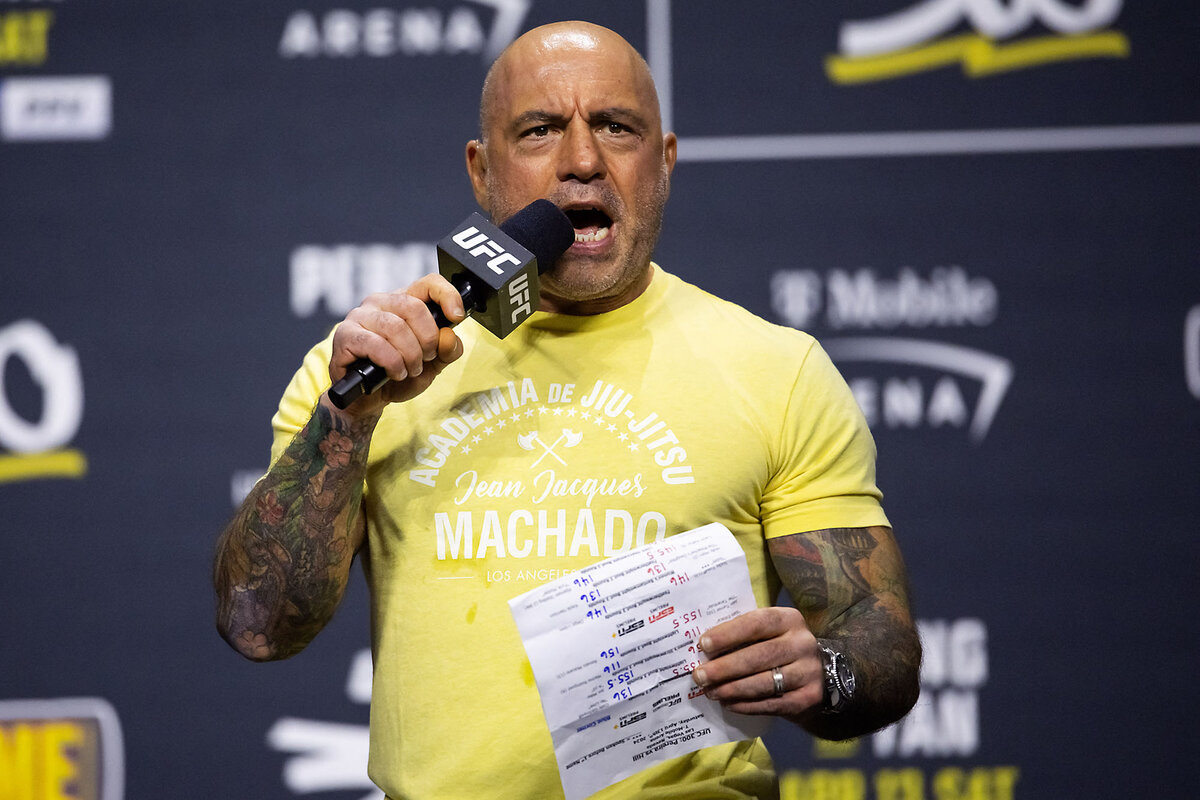

Younger radio audiences are gravitating to podcasters like Joe Rogan and Charlamagne tha God, who mix selectively sourced conversations about news with entertainment and eschew the conventions of journalism, says Ms. Vega, a former CNN reporter. “There’s a [quality] of relatability that people like Joe Rogan have, for better or worse. They’ve found an opening. People say, ‘This guy is one of us,’” she says.

Mr. Oinounou says he builds trust with his Mo News followers by showing his work – stories are credited to original sources – and by admitting the limits of his knowledge, not hyping his hot takes. He tells readers, “I don’t know what’s going to happen here, but here are a few ways to think about it.”

He also encourages his readers to go to well-sourced reporting by outlets like The New York Times so they can better understand the complex stories he summarizes. Some tell him that there’s no need, since he’s already “vetted” the story; the trust runs to him and through him, but no further.

“It’s very interesting to hear the lack of trust in official sources,’’ he says. “It’s almost as if [when] you take it through somebody, that somehow brings more trust.”

India tries to balance risks and rewards of AI

Indian society is scrambling to respond to an uptick of political deepfakes during critical elections. Its efforts could help build a roadmap on how democracies balance the good and the bad of artificial intelligence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

This year, the World Economic Forum designated manipulated and falsified information as the most pressing short-term risk facing the world today. India is especially concerned with misinformation, which is exacerbated by the widespread use of artificial intelligence.

Surveys show most Indians have encountered AI-generated deepfakes in the past year. Some of that content has arguably benefited India’s democracy, with many parties embracing AI tools to improve voter outreach and translate political speeches. But since elections began April 19, there’s been a surge of deepfake videos harnessing the likenesses of politicians and celebrities to manipulate voters.

Last week, a doctored video of India’s home minister promising to dismantle benefits to lower castes sparked a political firestorm and led to several arrests.

Throughout India, individuals, tech companies, and fact-checking organizations are trying to mitigate the risks of this rapidly advancing technology. Other countries are paying attention.

“We have to grow resilient in the face of these new tools,” says Josh Lawson, director of AI and democracy at the U.S.-based Aspen Institute. “AI tools can be used to bridge language divides and to reach a broader audience with vital civic information. But the same tools can be used to try and manipulate voters at key moments.”

India tries to balance risks and rewards of AI

India’s marathon elections – which last six weeks and involve nearly a billion voters – are offering the world a glimpse into the promise and perils of rapidly advancing artificial intelligence.

A survey by cybersecurity company McAfee found that, in the last 12 months, more than 75% of Indians online have seen some form of deepfake content – video or audio that’s been manipulated through AI technology to convincingly imitate another person.

Some of this content has arguably benefited India’s democracy, including the ruling party’s use of AI tools to make Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speeches available in different languages. But since elections began April 19, there’s been a surge of viral videos harnessing the likenesses of politicians and Bollywood celebrities, seemingly to sway voters ahead of a constituency’s polling period.

Last week, for example, a doctored video of India’s home minister promising to dismantle benefits to lower castes sparked a political firestorm and led to the arrest of several people allegedly involved in its creation.

The escalating frenzy surrounding these deepfakes prompted a lawyers’ consortium to petition the Delhi High Court to compel India’s Election Commission to ban the use of deepfake technology in political communications – a petition the court declined this week. Elsewhere in India, individuals, tech companies, and fact-checking organizations are stepping up to try and manage this crisis. Experts say their efforts could help other countries that are preparing for elections.

“We have to grow resilient in the face of these new tools,” says Josh Lawson, director of AI and democracy at the U.S.-based Aspen Institute. “AI tools can be used to bridge language divides and to reach a broader audience with vital civic information. But the same tools can be used to try and manipulate voters at key moments.

“Civil society groups, campaigns, regulators, and the voters all have a role in defending fact-based reality,” he adds.

India’s AI experiment

For years, Indian political parties have been embracing AI technology to improve voter outreach. During the most recent campaign season, many partnered with digital production companies to deploy highly personalized audio messages or videos – including of deceased party leaders encouraging people to vote for certain candidates.

As the demand for such content grew, these companies formed a coalition to create guidelines for ethical AI usage that respects human rights, privacy, and transparency. Their standards, for example, prohibit content that defames opposition leaders and require videos to have a clear stamp noting they’re AI-generated.

Senthil Nayagam, founder of southern India tech startup Muonium AI and founding member of the coalition, says the effort fosters responsible practices and helps build public trust. “Ethical coalitions can work proactively to understand and mitigate the negative impacts of AI on society, such as job displacement, bias in AI systems, and other social and economic consequences,” says Mr. Nayagam.

Yet as free AI tools become more available, some argue that companies are not equipped to contain the technology or regulate its usage. Indeed, the recent viral deepfakes do not adhere to any ethics guidelines, and it’s this kind of overtly deceptive content that’s alarming rights groups and voters alike.

Turning discussion into action

This year, the World Economic Forum designated manipulated and falsified information as the most pressing short-term risk facing the world today. India is among the nations most concerned with the proliferation of misinformation, which is exacerbated by the widespread use of generative AI and has the potential to destabilize democracies, according to the Forum’s Global Risks Report 2024.

That report inspired seasoned political strategist Sagar Vishnoi to join hands with Pranav Dwivedi, a policy consultant, to educate public servants on the risks of deepfakes. The childhood friends both have experience with AI, but it’s only recently that they began discussing the immense threats AI-generative technology can pose to society.

“We are living in an era where technological advancements have blurred the lines between reality and fabrication,” says Mr. Vishnoi. “After multiple brainstorming sessions, we decided to launch the training workshops.”

Their first workshop, held April 5 and 6 in the Shravasti district of the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, drew a diverse group of over 150 attendees, including dozens of police, district judges, and senior administrators. Many were AI novices.

The two three-hour sessions delved into the intricacies of fake news and manipulated videos, using real-life examples and potential election scenarios to illustrate their impact. The group practiced scrutinizing media for visual and auditory cues that suggest manipulation. They were also taught how to use subscription-based tools like Deepware and InVID, with Mr. Dwivedi and Mr. Vishnoi emphasizing the importance of verifying information with credible sources.

The workshops – which are paid for by the local government and hosted by Mr. Dwivedi’s organization, Inclusive AI – are designed by Mr. Vishnoi and Mr. Dwivedi and feature legal, AI, and cybersecurity experts.

“There are so many anti-misinformation campaigns around the world, and I am trying to learn more from them,” says Mr. Vishnoi, listing off a slew of AI projects he’s following. “They are all trying to make citizens aware about the digital threat.”

Scheduling workshops with administration officials has been challenging during elections, but Mr. Vishnoi says multiple states have requested training and their next event – with a women-focused group near Delhi – is on the books for next week. The duo is also reaching out to banks to participate in future events, given their susceptibility to financial scams.

Meanwhile, other groups are working to arm the general public with tools to combat deepfakes.

Empowering voters

Last month, Misinformation Combat Alliance – a coalition of media, tech, and fact-checking organizations – launched the Deepfakes Analysis Unit (DAU), a resource that allows anyone to forward a piece of media to a WhatsApp number, and receive expert assessments on the authenticity.

This initiative, which supports multiple languages including English, Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu, leverages a diverse network of academicians, researchers, tech platforms, and fact checkers. The reports aren’t immediate, but while users wait, they can browse past assessments on the coalition’s website, or join the DAU WhatsApp channel for more updates.

During its launch, journalist and DAU head Pamposh Raina described the project as “India’s first tipline to help citizens discern between real and synthetic media” and said it will focus on “audio and video that could have the potential to mislead people on matters of public importance, and could even cause real-world harm.”

It’s a concern that resonates around the world, including in the United States, which holds elections Nov. 5.

According to a recent Polarization Research Lab report, 49.8% of Americans expect AI to have negative consequences for the safety of elections, 65.1% are worried that AI will harm personal privacy, and 50.1% anticipate elections becoming less civil due to the use of AI.

In the coming weeks and months, India could offer lessons on how to mitigate that damage – and even how to harness AI for good.

“The late date of U.S. elections means their citizens benefit from a year of learning abroad,” says Mr. Lawson, from the Aspen Institute.

Podcast

A woman of Gaza on what Gaza’s women face

With courage and calmness, our reporter in Gaza has delivered a vital perspective on a war that’s now six months in. As a woman, she has been especially attuned to the conflict’s strain on mothers, daughters, and sisters. She joins our podcast with a full read of a recent story.

Ghada Abdulfattah would like you to know about Gaza, her home.

She talks of its people’s generosity. Of fresh fish and strawberries during better times. She talks of a new war that began last October, one that she then began covering for the Monitor, and one that she says “transcends any war I have previously witnessed” in its ferocity and the deprivation it has caused.

“While no one remains untouched by the ravages of war in Gaza, women bear the heaviest brunt,” Ghada says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast.

A recent story of Ghada’s depicted that burden. In reporting it, she heard from women giving up food so that their children could eat. From a woman who cut off her hair, and her daughter’s, because of the challenge of maintaining hygiene, often using seawater.

“With each passing day, as the war raged on,” Ghada says, “what was once considered taboo for women became a norm.”

She recalls a woman on a school bench, her face weary, awaiting news of a son missing for months.

“She asked me, ‘When will it end?’” Ghada says. “Alas, no one knows the answer.” – Clayton Collins and Mackenzie Farkus, with full story read by Ghada Abdulfattah

Find story links and a transcript in our show notes.

Writer’s Read: What Gaza’s Women Endure

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Trust flows on a river undammed

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Earlier this week, the state of California stuck a shovel in the third of four hydroelectric dams being demolished on the Klamath River, which wends its way through Northern California from Oregon to the Pacific.

Removing those structures is the first step in the most ambitious experiment in nature restoration in American history. The goal is to save wild salmon, a once-abundant resource that anchored the region’s economy and shaped its Indigenous societies. “It’s going to be a very, very, very healing experience to be able to see the salmon come back,” says Kenneth Brink, vice chair of the Karuk Tribe. “It’s like a new beginning.”

Yet more than fisheries may be renewed. The project marks another example of rethinking humanity’s relationship with nature at a turning point in global environmental welfare.

Trust flows on a river undammed

Earlier this week, the state of California stuck a shovel in the third of four hydroelectric dams being demolished on the Klamath River, which wends its way through Northern California from Oregon to the Pacific.

Removing those structures is the first step in the most ambitious experiment in nature restoration in American history. The goal is to save wild salmon, a once-abundant resource that anchored the region’s economy and shaped its Indigenous societies. “It’s going to be a very, very, very healing experience to be able to see the salmon come back,” Kenneth Brink, vice chair of the Karuk Tribe, told the Los Angeles Times in April. “It’s like a new beginning.”

Yet more than fisheries may be renewed. The project marks another example of rethinking humanity’s relationship with nature at a turning point in global environmental welfare. Restoring nature requires people “to make decisions about where and how to heal. To repair and to care. To make amends for the damage we have done, while learning from nature even as we intervene in it,” wrote Laura Martin, an environmental historian at Williams College in her book “Wild by Design: The Rise of Ecological Restoration.”

“Restoration is, by definition, active: it is an attempt to intervene in the fate of a species or an entire ecosystem,” she added. Or as Mr. Brink put it, restoration focuses on healing.

Off the coast where the Klamath meets the sea, for example, scientists and professional fishers are working together to restore kelp forests damaged by the warming of sea waters due to climate change. Elsewhere, marine biologists are cultivating and seeding more temperature-resistant corals to restore reefs.

The Klamath River project has been decades in coming. Five dams were built during the 20th century to harness hydropower and irrigate farms. Those dams flooded tribal lands. Over time, water quality and marine health declined. Prolonged periods of drought, likely exacerbated by climate change, turned the river and tributaries to trickles. Last month, California banned salmon fishing for a second consecutive year as annual spawning runs have collapsed.

Now, where humans once harnessed the river to produce power, they are releasing the river’s power to flush a century of stored sediment. Hatcheries are reintroducing salmon fry to restore natural runs. California is restoring tribal rights to once-flooded lands. Farmers and Indigenous communities are restoring spawning grounds and forging new water-sharing agreements.

If dams uniquely symbolize a restless human quest to use the natural world, their removal indicates a rebalancing of relationships – with nature and between peoples. “I suggest that we conceive of restoration as an optimistic collaboration with nonhuman species, a practice of co-designing the wild with them,” Dr. Martin wrote. “But we still have the responsibility to collaborate with one another, too.”

On the Klamath, restoring the river started with restoring unity and good will.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Seeing ‘a new heaven and a new earth’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

Praying to better know God and His creation as spiritual and intact equips us to treat each other and our planet with love and care.

Seeing ‘a new heaven and a new earth’

I saw a new heaven and a new earth....

And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband....

And there came unto me one of the seven angels....

And he shewed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb.

– Revelation 21:1, 2, 9; 22:1

As mortals gain more correct views of God and man, multitudinous objects of creation, which before were invisible, will become visible. When we realize that Life is Spirit, never in nor of matter, this understanding will expand into self-completeness, finding all in God, good, and needing no other consciousness.

Spirit and its formations are the only realities of being.

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 264

Viewfinder

Somber observance of World Press Freedom Day

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us this week. We wish you a wonderful weekend, wherever you are. Some of the stories we’re following for next week include Dallas’ new plan for policing high-crime neighborhoods, Israelis’ views of a potential Rafah offensive, and how professional care for sick people and older adults in Nigeria is lifting a burden off women’s shoulders.