- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Remembering those we should not forget

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

When does responsibility end? That’s a question in my story today about colleagues who worked with the Monitor in Afghanistan and are still there, at great risk.

America’s time in Afghanistan involved many difficult questions with no easy answers. But responsibility is, at its core, a matter of trust. We put our trust in these colleagues to protect us. Can we now protect them? We continue to work to bring them to safety, and today’s article is an attempt to ensure they are not forgotten. But the need remains, as does the hope of an answer.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

College class of 2024: Shaped by crisis, seeking community

From pandemic to protests, these college seniors have faced unusual challenges. Many long for community – and have learned something about building it.

-

Leonardo Bevilacqua Staff writer

-

Jasper Davidoff Staff writer

-

Ali Martin Staff writer

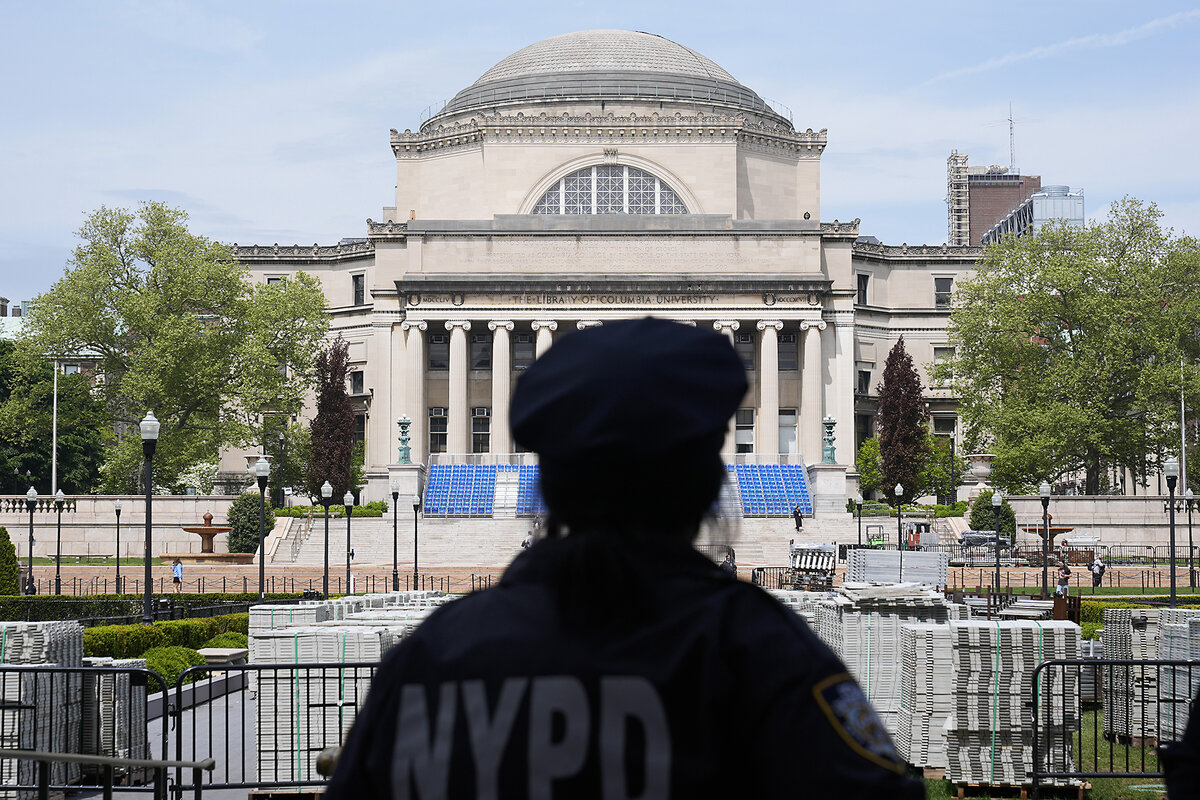

The class of 2024 began its college years as virtual students, arriving on once-vibrant campuses muffled by COVID-19.

Now they’re graduating from college during another season of turmoil, this time caused by protests about the war in Gaza that have swept colleges and roiled national politics.

As these seniors begin to pack up, many are seeking to make sense of their college experience amid fractious national political debates and rapid technological change. They have seen community fall away – and have learned something about building it back. They are celebrating their graduation, but with a mix of pensiveness, anxiety, and cautious anticipation.

Kristen Simpson, who will graduate from Berklee College in Boston on Saturday, says that she is hopeful about the future. “I graduated high school during COVID, so I didn’t get a graduation,” she says. “So this is my big celebration. There’s closure this time, which is good.”

College class of 2024: Shaped by crisis, seeking community

The class of 2024 began its college years as virtual students, arriving on once-vibrant campuses muffled by COVID-19. Most had missed out on high school graduations and proms. Now they’re graduating from college during another season of turmoil, this time caused by protests about the war in Gaza that have swept colleges and roiled national politics.

As these seniors begin to pack up, many are seeking to make sense of their college experience amid fractious national political debates and rapid technological change. They have seen community fall away – and have learned something about building it back. They are celebrating their graduation, but with a mix of pensiveness, anxiety, and cautious anticipation.

“It just felt like it went super fast,” says Wesley Mitchell, a senior film and TV major at New York University in Manhattan, who left his last class on Monday to enjoy the sunshine in nearby Washington Square Park. The first year was rough, he says. And now he’s graduating during a time of rancor over the Israel-Hamas war.

“There’s pro-Palestinian people on one side and then pro-Israel people on the other, and they’re just, you know, not talking,” says Mr. Mitchell. “Yeah, I totally get it. I feel like everyone kind of wants a community, but no one can come to terms on the same set of agreements.”

Still, Mr. Mitchell says he feels upbeat about graduating, given that his cohort of 2024 graduates has weathered so much. He reflects on the sense of liberation that came with an end to pandemic policies such as mandatory face masks, and how students came together again. He sees the same yearning for community in many protesters, even if he doesn’t share their politics or passions.

“Students started college so isolated because of safety precautions,” says Suzanne Rivera, president of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, which had a two-day occupation of a building in March that ended peacefully. “Many students who are at college today missed out on things like learning how to drive, or going to parties. ... They didn’t get to socialize or come of age in the traditional way.”

Like Dr. Rivera, university administrators nationwide are trying to restore normalcy to their campuses ahead of graduation ceremonies that could be disrupted by protesters. Columbia University in New York, Emory University in Atlanta, and the University of Southern California have decided to scale down or relocate commencements. At other universities, protest encampments occupy spaces usually given over to graduation events.

Seeking community and a cause

This specific cohort has experienced college life bookended by a pandemic and war in the Middle East. While outside political activists have been detained by police on some campuses, most protesters are current or former students.

For some, the camps have become spaces where volunteers take on roles such as distributing donated food and holding teach-ins and religious rites. And for a generation that feels disengaged from institutional culture, a “Gaza solidarity encampment” offers an alternative structure.

For others, though, the spread of the pro-Palestinian camps and the invective they often direct at pro-Israel members of the community is another reason to distrust institutions like universities that profess to be inclusive. For months, college presidents have faced criticism from some students, parents, and donors over antisemitism on campuses. Complaints about Islamophobia and intimidation of pro-Palestinian voices have received less attention.

Jason, a business senior at NYU, says the university has failed to provide a safe environment for Jewish students. This senior, who declined to give his full name, wore a kippa on his head as he watched a pro-Palestinian protest unfold in Washington Square.

“They weren’t able to provide for students first with COVID. And then once again, they’re failing us as well, albeit in a smaller demographic, but one that’s still important as well to the school,” he says, referring to Jewish students at NYU.

At her high school in central California, Patricia Martinez was politically engaged. But as an applied-math major at California State University, Bakersfield, she has focused on studying in order to graduate early. Her campus, she notes, has been relatively quiet.

A first-generation college student, she says her peers seem to tune out political news.

“I do believe that a lot of people choose to turn away. Maybe it’s just easier for them to either, I wouldn’t say be misinformed, but maybe not be informed at all in the first place. But I do think we should all at least know a little bit of something,” she says as she hands over a painting she has sold – one of her side gigs – to a friend.

After she spent her last two years of high school and her first year of college in pandemic-related isolation, Ms. Martinez’s strongest memories from this past year are of the friends she’s made.

“I think I actually got better at engaging with people,” she says. “There weren’t so many barriers anymore.”

Cal State Bakersfield serves a largely working-class student body – two-thirds are the first in their families to attend college – and the only protests this school year were led by faculty demanding better pay. “It’s kind of nice to be at a school that doesn’t have all this crazy stuff going on,” says Magie Uribe, a psychology major who will graduate next week.

When she’s not in class, Ms. Uribe coaches high school cheerleading and teaches children’s gymnastics and dance. This past year, she says, has been about trying to get by.

“I’m always working with the younger generation, who are so innocent,” she says. “It’s kind of nice, like an escape.”

Technology’s impact on community

Even before the pandemic emptied classrooms in 2020, students were showing rising levels of mental and emotional distress that, in some respects, forms the backdrop to the campus activism that erupted after Hamas attacked Israel last October.

Technology has fostered virtual interactions that can eclipse face-to-face encounters. Students spend more time on phones and laptops and less time socializing, studying, and eating with their peers on campus; participation in clubs and sports has decreased. Some of these shifts in behavior preceded the pandemic but were accelerated by virtual teaching and limits on student gatherings. As Zoom meetings replaced meet-ups, students adjusted to an atomized campus.

In the 2014-15 academic year, 20% of students reported a diagnosis of clinical depression, according to Healthy Minds, an annual web-based survey of students at more than 450 colleges and universities. By 2018-19, that share had risen to 36%. Last year (2022-23), it was 41%, which was down 3 points from the previous survey. Around 1 in 7 students said they had considered suicide in the past year. Anxiety and eating disorders have been rising.

Dr. Rivera at Macalester has seen how these challenges impact students and teachers, but she says that during this school year it feels like a corner has been turned.

“This year looked to me like the full college experience,” she says. Macalester will graduate 509 seniors Saturday on its quad. “We hope it will be a source of some healing for the grief that everyone felt four years ago when they missed out on graduation.”

Students are hoping so, too. On Thursday, Kristen Simpson and Hannah Freeman took advantage of a break in Boston’s sporadic rain showers to take photos outside in their caps and gowns. Ms. Simpson will graduate from Berklee College on Saturday, followed by Ms. Freeman, a theater major at Emerson College, on Sunday.

Even with family members coming from Colorado, North Carolina, and Oregon to Ms. Freeman’s graduation, the moment feels bittersweet.

“Emerson had a huge protest and a lot of arrests recently, so I’m curious to see how that affects the ceremony,” she says. “The state of the world is terrifying, and it’s weird to feel like I’m just going to walk across the stage to celebrate when there’s so much going on.”

For Ms. Simpson, a guitar performance major, Berklee’s Saturday ceremony is an important marker on her life journey and one she relishes.

“I graduated high school during COVID, so I didn’t get a graduation,” she says. “So this is my big celebration. There’s closure this time, which is good.”

Today’s news briefs

• Battles near Rafah: A United Nations official says heavy fighting between Israeli troops and Palestinian militants on the outskirts of the southern Gaza city of Rafah has left crucial nearby aid crossings inaccessible and caused more than 100,000 people to flee north.

• Confederate names decision: The education board for Shenandoah County, Virginia, votes to restore Confederate generals’ names to two public schools, becoming the first to do so in the United States.

• Video of Black airman’s killing: A Florida county sheriff released body-camera video of a deputy fatally shooting a Black airman holding a handgun in his apartment.

• U.N. vote on Palestinian membership: The United Nations General Assembly has voted 143-9 to grant new “rights and privileges” to Palestinians and has called on the Security Council to favorably reconsider their request to become a member.

• U.S. asylum shift: A new U.S. asylum change aims to more quickly reject asylum-seekers caught illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border if they pose certain criminal and national security concerns.

We tried to get these people out of Afghanistan. They’re still there.

Afghan colleagues who helped the Monitor report in Afghanistan for 20 years put their trust in us and in the United States. Now, some still can’t get out. They’re hoping something can change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

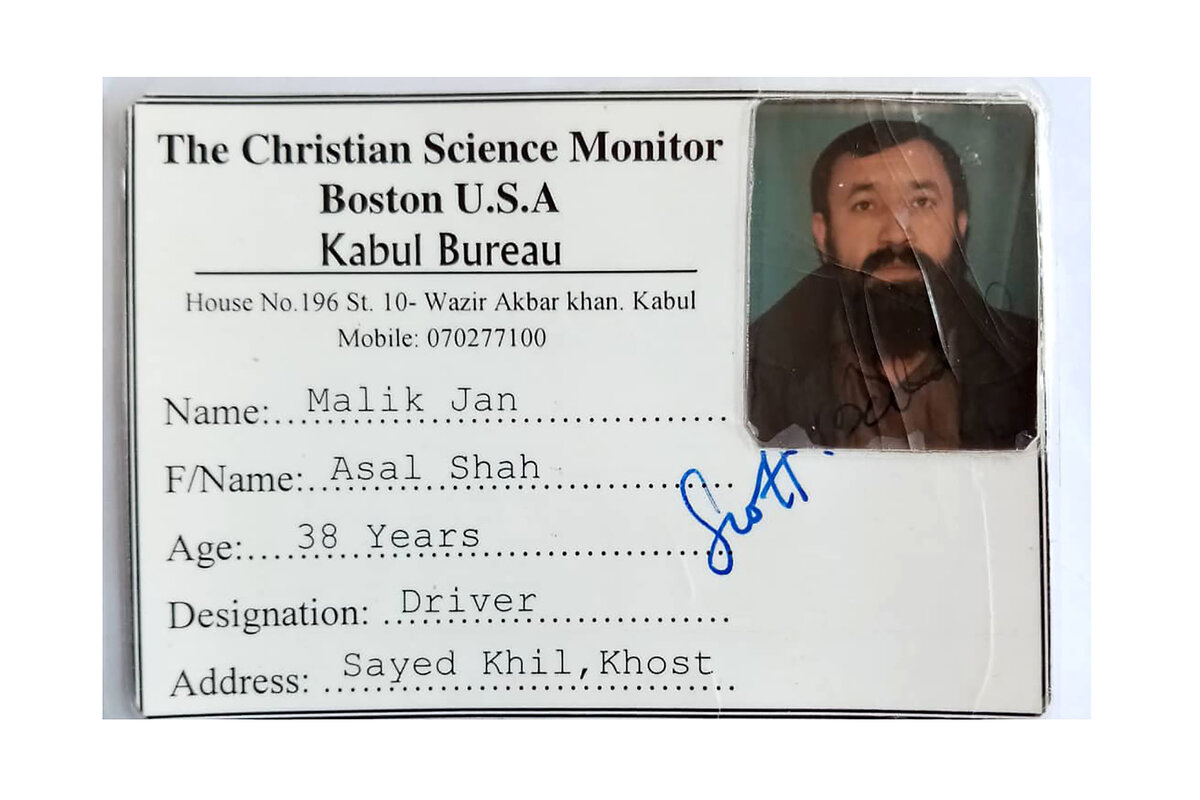

Technically, Malik Jan Zadran worked as a driver, helping Christian Science Monitor correspondents get to the far-flung corners of Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban. But really, he was a first line of security.

“If we planned to go to a province where the security was not good, my job was to do due diligence – talk to villagers, do my research,” he says.

Now, with the Taliban back, he is sitting in hiding, with no job, no way to feed his family, and his son killed because of the father’s connection to an American, Christian newspaper. “If we catch another son, we will kill him,” those threatening Mr. Zadran by phone still say. “We will behead you.”

Amid the United States’ chaotic exit from Afghanistan in 2021, the Monitor was able to help some of its colleagues escape the country. But some, like Mr. Zadran, remain. His claims for refugee status in the U.S. are moving, slowly. So Mr. Zadran waits – and hopes.

“It’s reassuring that people think of you,” he says, “that they care about what happens to you.”

We tried to get these people out of Afghanistan. They’re still there.

When Malik Jan Zadran decided to work with The Christian Science Monitor, it felt like a promise. He would protect his American colleagues. Yes, the Taliban had just fallen, but they lingered in the shadows and along the margins – in the places reporters most needed to go.

So Mr. Zadran went to work to keep his new friends safe.

“If we planned to go to a province where the security was not good, my job was to do due diligence – talk to villagers, do my research,” he says. “I would brief the reporters and take precautions. And I enjoyed every minute of it.”

But 20 years later, the situation has reversed. Now it is the Taliban who have taken over, and it is Mr. Zadran’s American colleagues who need to protect and help him. Today, he remains in Afghanistan, the Monitor unable to bring him or several other Afghans who worked with us to safety.

Now, 2 1/2 years after the fall of Afghanistan, the Monitor has had some success in helping to extract the colleagues who risked their lives to help us. But four remain. They were drivers, but also tour guides and purveyors of jokes to break the tension. They knew the best roadside stands for pomegranates on the interminably bumpy treks through dusty landscapes browned by a relentless sun. They shared succulent kebabs with Monitor reporters, including myself, as the hushed purples of the Hindu Kush evenings set in.

Mr. Zadran says he has already paid the price of a son – killed because Mr. Zadran took what the Taliban saw as the traitorous step of working for an American, Christian newspaper. Now in hiding, Mr. Zadran still gets calls: “You are a puppet of the Americans; you are a sick person. We witnessed that you served the Americans. Thank God we are letting you survive. You should be dead.”

All those years ago, he put his trust in the Monitor and in the United States. Now, his only recourse is to wait to see if American bureaucracy will move his paperwork along, and grant him and his family passage to safety. The process is grinding forward, slowly. But despite receiving some money from charitable outsiders who know his situation, Mr. Zadran is running out of funds. His family fears leaving the house. He has no job. Creditors are gathering.

“‘If you don’t pay,’” he says they tell him, “‘I will complain to the government.’”

“If they find out,” he asks, “what will they do with me?”

Mr. Zadran’s situation is not unique to former Monitor colleagues. America’s departure from Afghanistan after 20 years was abrupt and chaotic. The iconic image of someone clinging to the wheel of a departing aircraft spoke to the desperation and lack of order. The number of people whom the Taliban could reasonably consider traitors was immense, and few knew if they were getting out or not.

“To me, the country of Afghanistan and the people of Afghanistan did not deserve to be treated like this by the American government,” says Farouq Samim, who runs Operation Abraham, an organization based in Ottawa, Ontario, that helps Afghan refugees and those seeking to flee. So far, he has helped rescue 1,500 Afghans, from female judges to teachers to journalists.

Trailed by AK-47-toting Talibs

A State Department spokesperson declined to provide specifics on the Monitor’s cases, citing security and privacy concerns. But the Biden administration remains focused on expanding the resettlement of key populations, including Afghan allies, the spokesperson said.

Before moving to Canada on a scholarship in 2009, Mr. Samim also helped the Monitor and the Chicago Tribune as a translator, logistics manager, collaborator, and security team leader. Even then, things were becoming more dangerous by the year. Prior to his departure, two local journalists and close friends working for Western media were kidnapped and killed by the Taliban. One was beheaded along with his driver.

Mr. Samim left partly because he no longer felt safe. Yet “we never resented working for our American colleagues,” he says. “We put our lives on the line. We didn’t know such a shocking collapse would happen.”

Among those Monitor colleagues remaining in Afghanistan are Zubair Sayeed, Ajmal Naseri, and Mohammed Naashna. They primarily worked as drivers, though that term hardly captures the breadth of their work. Mr. Zadran remembers the time that one Monitor correspondent wanted to find Arab men who were coming to remote corners of Afghanistan to fight for the Al Qaeda cause.

Mr. Zadran volunteered for the job. It would be too dangerous for an American to come along, so he drove off in search of Arab fighters, following tips and hunches. When he found several, they refused to return to the hotel with him, so Mr. Zadran brokered a compromise – finding a middle ground where they all could meet. The Monitor got its story.

On another assignment for the Monitor, Mr. Zadran recalls being followed by a motorcycle-riding Talib toting an AK-47. Mr. Zadran, a translator, and a Monitor correspondent made for the safety of the local governor’s house as quickly as they could.

“The nature of the work was at times risky,” he says. “We had to be risk-taking to get close to the facts.”

Scott Baldauf, a Monitor writer who worked with him on many occasions, tells of a visit to a warlord of Mr. Zadran’s own tribe. They drove through what seemed an empty checkpoint, but suddenly, after 50 yards, the checkpoint bristled with men shouting and pointing rifles at the car.

Mr. Zadran calmly stopped, stepped out, “and talked the men down,” says Mr. Baldauf, who left the Monitor in 2012. “All I could think was that my life was in the hands of men like Malik Jan. He knew the culture, the people, how to make things happen, and, in this case, how to stop bad things from happening.”

In a separate email, Mr. Baldauf adds: “We felt that those stories helped to get a better understanding of why it was so difficult to bring lasting peace to Afghanistan. Now those stories have marked Malik Jan.”

Who got out and how?

Those Afghans who got out generally had better connections or a better idea of how to work through a system as it collapsed. Monitor contributor Zubair Babarkhail also worked for Stars and Stripes, the news publication of the U.S. military. In 2008, he was a fellow on a State Department trip to the U.S. for Afghan journalists.

He now lives in Pittsburgh, working for an organization that helps resettle Afghan refugees. But even for someone with connections directly to the U.S. government, the escape from Kabul was harrowing.

Thousands of people thronged the airport hoping to catch a flight out. For 10 days, Mr. Babarkhail had his three children sleep with their shoes on so they could leave at a moment’s notice. He would get calls in the middle of the night from friends in the military, telling him to be at a certain place at a certain time. Once, his family missed a shuttle bus into the airport by five minutes. Another time, he went without his family so he could go into the crowd, hoping to get closer to the gate and be seen by his colleagues.

Inside the crowd, “it was like a wave of water,” he says. “Everyone was stuck to another person.” He escaped a bombing during one trip to the airport. The crowd was tear-gassed during another of his trips.

How he and his family eventually got out, he says he cannot share. He hasn’t been authorized to speak about it publicly. Yet when he was at last on a plane bound for Qatar, then on to Germany and the U.S., there was no feeling of joy – only disbelief.

“It was not a happy moment,” says Mr. Babarkhail. “No one wants to leave a country like that. We were leaving behind everything we struggled for in our life.”

There have been moments of joy since – walks with journalist friends at a temporary refugee facility in Wisconsin, watching Afghan boys playing cricket there, and the “first time we saw blue skies in our lives.” (Yes, Kabul is dusty.)

But the transition has not been easy for his fellow Afghans. Some have never used electricity, he says. Others have never received mail in a mailbox. He says they wonder, “‘What is this about? Do I owe someone?’”

But their families are safe, which is all Mr. Zadran wants for his family.

Mr. Zadran’s household includes 21 people, and he insists on bringing them all, complicating his hopes. But he has already lost a son – killed even before the Taliban takeover when the son tried to visit another province. “If we catch another son, we will kill him,” those threatening Mr. Zadran still say. “We will behead you.”

So he has moved from place to place. Even going back to the village where he was born offered no refuge. Too many in his own tribe are too intertwined with the Taliban.

“I am an Afghan, and I am in a conflict zone and have always been in a conflict zone,” he says. “You can’t make any decision without risk. I worked for The Christian Science Monitor because it put food on my table for my family. I made that choice, and that was the risk.”

Still, he says, “I am grateful for the work done for The Christian Science Monitor.”

And he is grateful that he has not been forgotten. “It’s reassuring that people think of you, that they care about what happens to you.”

Mr. Samim of Operation Abraham talks to Mr. Zadran once a week, offering comfort and hoping for progress on his refugee case. “Every night I go to bed, I’m thinking of them,” says Mr. Samim of those left behind. “My children are safe.”

“These people protected American lives; they provided a safe environment,” he says. “They are friends in need.”

Podcast

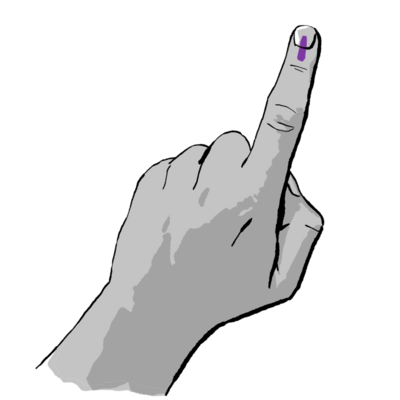

In India’s election, a towering test for democracy – and our reporter

Covering an election in a sprawling nation of 1.4 billion people naturally comes with logistical hurdles. Finding a way to frame it through the lens of a universal value – trust – adds to the challenge. Our India correspondent joins his editor on our podcast to explain.

India’s massive weekslong election could serve as a litmus test for the country’s democratic spirit.

Over the past decade, India has witnessed an increase in religious division, media censorship, and arrests of political opponents – all factors that “have largely affected the democratic character of the country,” says India correspondent Fahad Shah on the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast. “And that has been the main point of the opposition in this election.”

Fahad recently traveled to Udhampur, India, to see whether the country’s democratic backsliding was hurting political participation. He found that mistrust had taken root among average voters. Many worried about the reliability of electronic voting machines and the integrity of the Election Commission of India. But these concerns weren’t stopping them from casting their ballots.

“We met people who are ... walking miles to vote,” he says.

Results are expected early June. Until then, Fahad is keeping an eye on how extreme weather impacts voting, and sifting through an onslaught of online debate and viral deepfakes.

“Everybody is watching how AI is playing a role in this election,” he says. “I think this will kind of become a benchmark for other elections.” – Lindsey McGinnis and Mackenzie Farkus

For story links and a transcript, click here.

Looking for Trust as India Votes

This retired Marine pilot aims to be the role model she never had in Afghanistan

For a long time, Marine aviation was a man’s job. This retired helicopter pilot aspires to be the role model she didn’t have two decades ago.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Daniel Langhorne Contributor

Alexis Federico, who served in the Marines for a decade, has a mission these days that is no less important to her.

As a board member for the Flying Leatherneck Historical Foundation, Ms. Federico is working to relocate a Marine aircraft collection of more than 40 jets and helicopters. Their new home would be the Great Park, a popular public space built on part of a decommissioned base in Irvine, California. By building an aviation museum in the heart of the Great Park, Ms. Federico and a group of fellow retired Marines hope to educate the next generation about military service and maybe inspire interest in STEM careers.

Ms. Federico wants the future museum to open children’s eyes to all the pathways available to them. Besides publicly sharing her story of military service and her vision for diversity in the exhibits, Ms. Federico, an attorney, supports the Flying Leatherneck foundation’s board by parsing legal contracts with donors.

Whatever children do in life, she says, “you want them to walk [into the museum] and be like, ‘Wow, there’s a woman doing that’ or ‘Wow, that person looks like me.’”

This retired Marine pilot aims to be the role model she never had in Afghanistan

Alexis Federico remembers being behind the controls of a roaring UH-1Y helicopter as it circled over mud-brick houses in Nawzad, Afghanistan, a Taliban stronghold. Her mission: Make sure no one harassed the Afghan girls walking to their schoolhouse with their fathers.

“We were over there providing support,” explains Ms. Federico, a decorated retired helicopter pilot. “They’re going to school, and we’re just watching them. I had a lot of great experiences in the Marine Corps, but for me, that was so, so great.”

Ms. Federico, who served in the Marines for a decade, including in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010, now lives in Dana Point, California. But her mission these days is no less important to her.

As a board member for the Flying Leatherneck Historical Foundation, she is working to relocate an unmatched Marine aircraft collection of more than 40 jets and helicopters. Their new home would be the Great Park, a popular public space built on part of a decommissioned base, Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, in Irvine, California. By building a modern aviation museum in the heart of the Great Park, Ms. Federico and a group of fellow retired Marines hope to educate the next generation about military service and maybe inspire interest in STEM careers.

Passion for diversity

Ms. Federico says she would love for the future museum to open children’s eyes to all the pathways available to them. Besides publicly sharing her story of military service and her vision for diversity in the exhibits, Ms. Federico, a practicing attorney, has supported the Flying Leatherneck foundation’s board by parsing legal contracts with donors. She will also have a role during fundraising events for the museum.

“One of the things I’m passionate about on the board is making sure there’s representation,” she says. “It’s great to have museums that reflect what the military looked like back then, but the military looks very different now. It’s a lot more diverse, and you want that reflected not just because you hope some child is going to grow up and want to be a Marine aviator, aircraft mechanic, or logistician. Whatever they do in life, you want them to walk [into the museum] and be like, ‘Wow, there’s a woman doing that’ or ‘Wow, that person looks like me.’”

From 1989 to 1999, the aircraft and assorted aviation artifacts – including jet engines, photographs, maps, and a large collection of squadron patches – had been housed at El Toro until its permanent closure. The items were then moved south to Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. Over the years, a Vietnam War-era Pioneer drone was also acquired. These items were on display until the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2021, Miramar’s former commander declined to assist in reopening the museum because of budget constraints, says retired Marine Brig. Gen. Michael Aguilar, president and CEO of the Flying Leatherneck foundation. A group of retired Marine aviators who lead the foundation approached Irvine city officials with the idea of returning the collection to its previous home in Orange County. The foundation plans to construct the new museum at the Great Park, assuming the completion of a $46 million capital campaign. Irvine has provided a $20 million grant, and private funders have given an additional $6 million. Mr. Aguilar anticipates the museum could open in 2026.

In early March, a convoy of three trucks delivered the first batch of the museum’s collection – a MiG-15, an F/A-18A Hornet, and a T-34 Mentor – to the Great Park. Foundation members wearing red polo shirts and flight caps filmed the long-awaited homecoming at the cavernous hangar.

“Exactly what we need”

Retired Marine Col. Patrick “Paddy” Gough met Ms. Federico when she was an instructor with Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One based in Yuma, Arizona. After retiring with 30 years of military service, Mr. Gough joined the Flying Leatherneck board. He says it was composed of older, white, male retirees and in desperate need of new voices until Ms. Federico joined. “Alexis brings her knowledge of the law, and that’s key for us when we started looking at contractual requirements with the city [of Irvine],” Mr. Gough said. “She’s exactly what we need.”

Olivia Weber was a first-year law student at the University of California, Irvine in 2014 when she met Ms. Federico while both worked cases for the International Refugee Assistance Project. Although Ms. Federico was only a year ahead of them at the law school, Ms. Weber and her classmates looked up to Ms. Federico because of the experience and wisdom she acquired in the military. Both women ended up working for the same law firm. “She just always carries herself with such presence,” Ms. Weber says of Ms. Federico. “She is a true defender of her positions.”

Ms. Weber was also impressed by how her colleague worked long hours at the firm and then volunteered at an animal shelter every weekend caring for rabbits. “Nobody wants to volunteer for the bunnies, but Alexis does,” Ms. Weber says.

Ms. Federico also has used her post-service law training to support Afghan allies in navigating asylum cases. She successfully petitioned the State Department to grant a Special Immigrant Visa to a former Afghan interpreter, Farid Zahiri, who had assisted her husband when he served in Afghanistan as a Marine aviator.

After Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, the Federicos enlisted the aid of a California lawmaker to reunite Mr. Zahiri with his wife and mother on U.S. soil. Ms. Federico also took on a pro bono asylum case for a female engineer and Fulbright scholar from Kabul University who had cold-called her firm. The Afghan woman had returned to her home country to help the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rebuild and to start a nonprofit to recruit more women into the construction business. She immediately received death threats.

Ms. Federico’s family has a history of military service. She grew up on the move with an Air Force dentist as a father. Her grandfather served as a helicopter crew chief in the Korean War. She vividly remembers when they flew in a private plane and let her handle the controls for the first time.

In 2003, when she earned her commission from the Marine Corps, it was normal to be the only female pilot in a helicopter squadron, Ms. Federico recalls. Women flying the same aircraft had yet to rise through the ranks. Two decades later, she strives to be the role model she didn’t have.

At her suburban home, an infant bouncer for Ms. Federico’s young daughter dangles in the kitchen doorway. Four rabbits that the family fosters are corralled in the garage. In a large painting in the dining room, a rabbit stands at attention wearing a crimson Napoleonic War-era hussar uniform.

“Change the things you can change,” Ms. Federico says. “I can complain the government isn’t doing XYZ, but I can help out one person, volunteer at an animal shelter, and help open a new museum.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

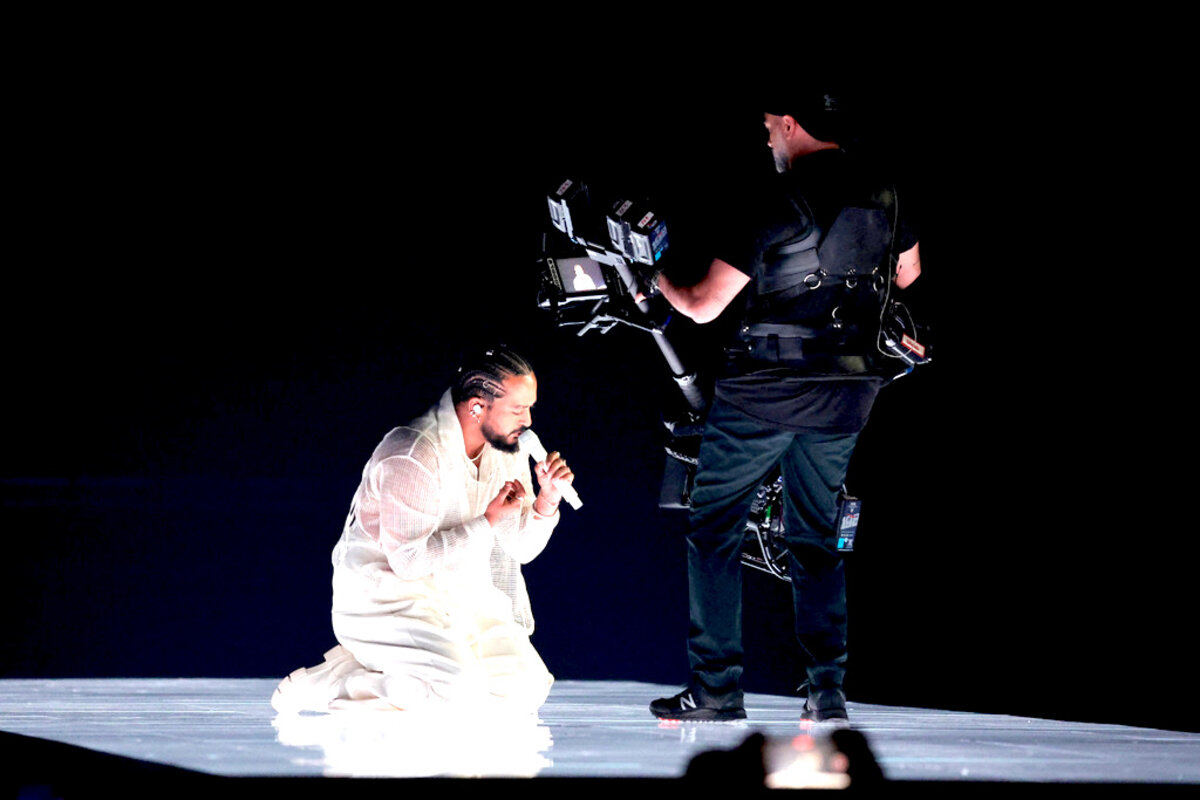

Eurovision shapes the Continent’s identity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In April, French President Emmanuel Macron described Europe as “a continent-world that thinks about its universality.” Perhaps he would include thinking about singing, that most universal of languages.

On Saturday night, an audience of more than 150 million people is expected to watch performers from 26 countries in the Grand Final of the Eurovision Song Contest. The event, now in its 68th year, will again shape a tighter European identity that honors the singing talent from individual countries.

The “universal” in Eurovision lies in its democratic and inclusive nature. Viewers get to vote on who wins. And the event’s organizer, the European Broadcasting Union, is quite open about its struggles to welcome new countries while keeping the musical competition as free of geopolitics as possible.

In June, more than 400 million EU citizens will elect a new European Parliament. That contest, even if it does help cement EU values in governance, has so far drawn less interest than the Continent’s annual celebration of original, three-minute pop songs – and the democratic voting behind it. The world’s largest and longest-running live music contest is central to the European project, one universal note of song at a time.

Eurovision shapes the Continent’s identity

In April, French President Emmanuel Macron described Europe as “a continent-world that thinks about its universality.” Perhaps he would include thinking about singing, that most universal of languages.

On Saturday night, an audience of more than 150 million people – larger than the Super Bowl – is expected to watch performers from 26 countries in the Grand Final of the Eurovision Song Contest. The event, now in its 68th year, will again shape a tighter European identity that honors the singing talent from individual countries, most of them in the European Union.

The “universal” in Eurovision lies in its democratic and inclusive nature. Viewers, along with an expert jury, get to vote on who wins. And the event’s organizer, the European Broadcasting Union, is quite open about its struggles to welcome new countries while keeping the musical competition as free of geopolitics as possible.

This year hasn’t been easy. Israel’s contestant, Eden Golan, was asked to revise her song to avoid an allusion to the Hamas attack last October. But organizers rejected pleas to ban her. As a result, protesters are descending on the Swedish city of Malmö, the site of this year’s contest. (Sweden put Eurovision on the global map in 1974 when ABBA won with “Waterloo.” This year, it may be known for upholding the freedom to protest.)

Eurovision has become a mirror for the values that the EU wants to spread to prevent ethnic-based wars like World War II. For many of the bloc’s newest members, the key value is freedom, especially freedom of expression and assembly. After the former Soviet state of Estonia won the contest in 2001, its then-leader said, “We are no longer knocking at Europe’s door. We are walking through it singing.”

In June, more than 400 million EU citizens will elect a new European Parliament. That contest, even if it does help cement EU values in governance, has so far drawn less interest than the Continent’s annual celebration of original, three-minute pop songs – and the democratic voting behind it. The world’s largest and longest-running live music contest is not just entertainment. It is central to the European project, one universal note of song at a time.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our divine Mother loves us

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Roya Sabri

The love we receive from God is boundless, and as we understand this fact, we find it expressed in our lives.

Our divine Mother loves us

A mother’s love can be so tender, comforting, and lasting. Poet Lola Ridge put it well, writing in “Mother,” “Your love was like moonlight / turning harsh things to beauty....”

And yet, no matter how powerful the love of a mother may feel, the relationship still has its limits. Many people have never known their mother. Others have had their mom around, but the relationship hasn’t been smooth sailing. And what happens when our mother passes away? This all can make us wonder if mother-love is ultimately variable and fleeting.

The Holy Bible draws on the image of motherhood as a symbol for how much God loves and cares for Her children. In the book of Isaiah, God says, “As one whom his mother comforteth, so will I comfort you” (66:13). But the Scriptures draw the distinction that, unlike the affection that can come from a person, God’s love is truly infinite, a ceaseless fountain of care that never runs dry.

John’s first letter says that God is Love itself (see 4:8). What a thought ... that the creator of the universe is Love. Therefore God has no spot of hatred, anger, unkindness, apathy, discontent. As our Father-Mother, God is the ideal Parent – eternal and wholly good.

In the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy defines “Mother” as “God; divine and eternal Principle; Life, Truth, and Love” (p. 592).

As the children of God, we are also eternal and good, forever spiritual – forever at one with our divine Mother. That’s why human mothers can express such comforting love. In truth, all any of us can do is express love from God.

What a joy it is that we receive all the love we need directly from God. Christian Science brings out that whenever we feel spiritual love, it’s from our divine Mother. It’s an intimation of the grandness and completeness of divine Love filling all space, always with us, caring for us.

It takes turning away from an imperfect, material view of love to see how the Divine is expressing Herself in our lives. I’ve experienced this in my practice of Christian Science.

Growing up, there were certain circumstances in the family that meant my grandma and I just didn’t have a close relationship, even though we were often together. There came a time when I was going to visit her for a few days, and it would be just the two of us.

I was nervous about this trip. But through my study of the Bible and Science and Health, I knew there was a higher view to glean about my grandma and me. During my six-hour drive to see her, I reached out to God to glimpse more of this spiritual perspective.

As I prayed, I heard the message that my only job is to love. This was so powerful and clear that for most of that drive I just let it sink in. I became so focused on loving with a pure spiritual love that only sees God’s goodness and its expression, that my fears about the relationship were no longer part of my thinking. They had faded away.

From that time on, I felt a deep affection and support in our relationship that I cherished. And the bad memories that had before drawn a rift between us didn’t seem powerful or relevant anymore. I suppose we were seeing more of how divine Love loves us.

It’s so comforting that our divine Mother does love each of us so purely, including those precious people we call our mothers. This love isn’t ever inaccessible to us. At any moment, we can gratefully accept more of the goodness God is giving us. By basking in the free flow of God’s blessings, we can let any “harsh things” in our lives be transformed into beauty.

Viewfinder

The perfect shot

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us before starting your weekend. Next week, we’ll be on the news with several stories about how Israel and Gaza are viewing the events of the past weeks. But we’ll also take a fun look at how “The Thursday Murder Club” book series is helping make sleuths of a certain age trendy again.