The 'wind rush': Green energy blows trouble into Mexico

| San Mateo del Mar, Mexico

The Isthmus of Tehuantapec, Mexico's narrowest point, is a powerful wind tunnel of air currents whipping through the mountains that separate the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Here, on the Pacific side, the wind shapes everything from the miles-long sandspits of Laguna Superior to the landscapes of the indigenous people's hearts.

Howling constantly through thatched roofs, the wind is powerful enough at times to support a grown man leaning back as if in a chair. Gales average 19 miles per hour, slapping waves over the bows of fishing skiffs and sandblasting anyone standing on the beach.

The wind is "sacred" in this village, says indigenous Huave fisherman Donaciano Victoria. "We believe that the wind from the north is like a man and the wind from the south is like a woman. And so you must not disrespect the wind."

North, in the town of La Venta, one woman says that when she leaves the isthmus, she's struck by how still the rest of the world is.

Others have noticed, too: There are few places like this on earth.

This isolated region of the state of Oaxaca is one of the world's most continuously windy spots. And because wind is a valuable commodity in a world seeking alternative energy, a "wind rush" – reminiscent of the gold and oil rushes of other eras – has swept into the isthmus.

Wind energy companies have swarmed to the area with big plans for wind farms to power the likes of Coca-Cola plants and Wal-Marts and a push to acquire huge tracts of land to do so. The "rush" for land farmed by locals since ancient times has divided the impoverished indigenous population over money, land rights, and changing values. Villagers' distrust of outsiders has led to increasing unrest throughout the Pacific edge of the isthmus for several years. Most recently, around the Laguna Superior, it has included a paralyzing blockade of one village by another and, in October, a deadly shooting at a demonstration.

"Oaxaca is the center of communal landownership. There is probably no worse place to make a land deal in Mexico," says Ben Cokelet, founder of the Project on Organizing, Development, Education, and Research.

And yet, with such an overwhelming wind resource, it was bound to attract development. The rush for Tehuantapec's wind energy is a green-tinged twist in the age-old story of resource extraction: The quest for "clean" energy isn't always so clean.

Farmers shocked at size of turbines

Mexico's potential wind energy capacity is enormous: 71 gigawatts, which is 40 percent more than the nation's entire installed electricity-generating capacity, including coal, gas, and hydropower. That potential was behind Mexican President Felipe Calderón's promise at the 2010 United Nations Climate Change Convention in Cancún to double solar and wind energy production from 3.3 percent of the nation's energy production to 7.6 percent in just two years (a goal Mexico is on track to hit later this year).

"And," Mr. Calderón noted then, "the Isthmus of Tehuantapec is the area of greatest wind energy potential in the world."

Wind developers have known this since the mid-1990s, when they first targeted land here for wind farms. Today, the region's wind production is about 2,500 megawatts (enough to power, given the nearly constant wind, about 870,000 US homes).

The first town to see turbines was La Venta (pop. 2,000), north of Laguna Superior. Today, rows of turbines surround the town. The howl of the wind is now punctuated with the rhythmic sound of windmills.

"Whenever I am working there is this never-ending sound – thrum, thrum, thrum," says Alejo Giron Carraso, a La Venta farmer who works in the shadow of monstrous turbines.

For those without land, the development has been a boon.

"It's helped us a lot. Our parents are old and we didn't have much. For a lot of the people in this community it's meant a lot of work," says a woman identifying herself as part of the Betanzos family that runs a small La Venta restaurant.

For those with land, who have depended on farming, the economics are more complex: Most of the land here is communal – analogous to native American reservations – held by Zapotecs, the dominant indigenous group in southern Mexico. Decisions to lease land to devel-opers are made by local leaders, but the prices paid for individual land parcels are a patchwork of values that have led many farmers to feel cheated where turbines are already up and running.

Many locals who have given up land are illiterate and not savvy about the process. They recall meetings with developers in which model windmills the size of dinner platters were shown, leading them to believe they could continue farming around them. But they were shocked to see 15-to-20-story turbines rise across acres of their land.

Some claim their land was permanently damaged by construction or that they are no longer allowed on it. Others say they were pressured to sell land rights for a fraction of their worth and that community leaders got better deals for their land.

"The first guy or two that bites gets [$8] per square meter. That's a hundred times better contract than the other people," says Mr. Cokelet. "But the 98 percent of farmers who sign afterwards sign on for rock-bottom prices. Those one or two people who bite – they don't bite because they're lucky. They bite because they know someone. And their job ... is to sell it to all their neighbors."

While wind developers involved in the La Venta wind farms declined comment on specific contracts, other wind developers in the region admitted in Monitor interviews that the only way to acquire land in this communal setting is to deal with community leaders who may enjoy more benefit from signing first. Indeed, some were flown by the developers to Spain to see working wind farms.

The isthmus has a difficult history with outside investors. In the late 1800s the United States eyed it as a potential passage to Asia, and later as an alternative to the Panama Canal. In the 1990s, community groups fought off a Japanese attempt to build a shrimp farm in the shallow lagoon. More recently the state-run oil company Pemex has crisscrossed the region with pipelines that have leaked.

So the region's notoriously prickly view of outsiders has made the isthmus a difficult place to develop.

"People kept telling me, 'You know we've been experiencing globalization for a really long time,' " says Wendy Call, who has written about the isthmus and notes that the Aztecs invaded first. "But I think there is a sense of fatigue, [that] 'all the other times this has happened it hasn't gone well for us.' " [Editor's note: The original version misquoted Ms. Call as saying the Aztecs were invaded first.]

Most of Tehuantapec's communal land cannot be sold, so companies lease. A standard contract lasts 30 years, with automatic renewal.

Wind farm developers in La Venta pay a third to a sixth of what energy developers do in, for example, southeast Wyoming (the only comparably windy place in North America).

But comparisons are deceptive. Wind farms pay – either as profit sharing or flat fee – based on how the land is used: for turbines, roads, or power lines. In Wyoming, a landowner may lease hundreds or thousands of acres to a developer for tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. In the isthmus, most farmers control only two to 20 acres: If a turbine doesn't land on one's plot, payout may be as little as $300 to $400 per year.

Profit sharing in developed countries falls close to 5 percent. But in Oaxaca the market rate was determined to be 1 percent, says Jorge Megías Carrión, director general of Preneal, a Spanish company developing a wind farm here. "So we negotiated with the people, and we saw that we could enlarge that amount of money."

Preneal now pays landowners 1.4 percent of electricity profits. Acciona, another Spanish wind company working here, pays the equivalent of as little as 0.5 percent, according to landowners who signed contracts.

In Wyoming, landowners maintain access to their land, but here locals can lose the ability to work their small plots – either by being denied access or because turbine construction destroyed irrigation channels.

Anti-wind power graffiti now mars the walls of La Venta, and even some people who got a fair deal say their children are deserting the region because there is no future on the land.

Wind farm advocates say benefits go beyond just direct payments; wind farms bring much-needed jobs. Certainly wind farms demand a great deal of labor to build, but once running they are maintained by a few dozen highly skilled people, generally from the outside. However, many jobs are created to service those workers.

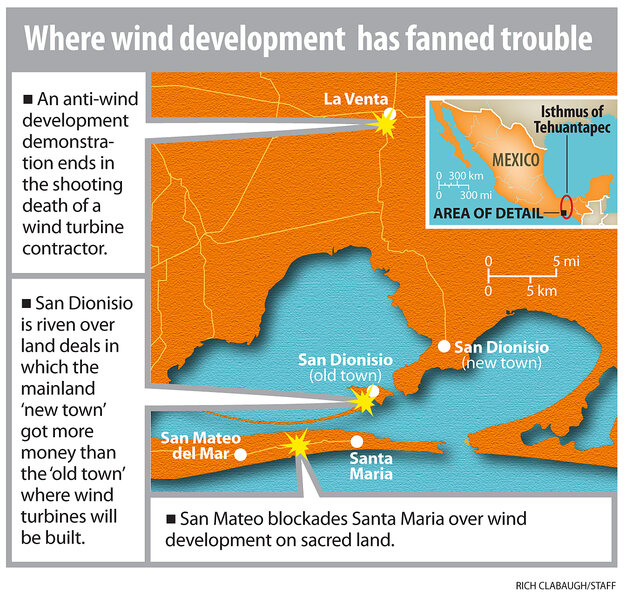

Still, in recent months people have started taking to the street to express dissatisfaction with La Venta's wind deals. In October, unrest turned deadly: A group of wind turbine contractors coming home from a project ran into anti-wind power protesters blocking a highway. Arguments led to scuffles, and one contractor was shot dead, say witnesses and relatives of the victim.

Wind companies say that a majority of locals support wind farms and suggest that unrest arises from old rivalries and misinformation.

But one Oaxaca State official disagrees, blaming foul public sentiment on previous administrations being too eager to encourage outside investment. "They didn't have experience in renewable energy. They didn't have experience in wind power. Of course they would have many errors," says Alejandro E. Velasco Hernandez, director of Renewable Energy for the state of Oaxaca, whose National Action Party won state control in 2010 from the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which had held it for 80 years.

"But," he adds, "now we have many opportunities to improve."

Wind is sacred – and lucrative

South from La Venta the shores of Laguna Superior are dotted with fishing villages of the Huave people. Here since ancient times, they've dwindled to a population of less than 20,000. The lifestyle in this area is markedly different from that of the north: Pavement gives way to dirt roads; thatched buildings are common, with high walls to counter the wind; women wear traditional clothing; and illiteracy is high.

And here, where the wind is embraced personally as a spiritual force, there is a distinct unfriendliness toward outsiders. Local belief says the "male" wind shaped the land while the "female" wind brings shrimp – the main livelihood.

In 2004, Preneal proposed a 300-megawatt wind farm on 4,000 acres in the town of San Dionisio. The company had previously approached the Mexican government to set up offshore turbines in the lagoon, but the government demanded 7 percent of the energy profits. So Preneal approached the town – which is composed of two villages, Pueblo Nuevo (New Town) on the mainland and the smaller Pueblo Viejo (Old Town) on an "island" attached to land by a thin sandspit. Pueblo Viejo is perfect for turbines, offering offshore conditions in constant wind without having to build in water.

Preneal offered the town 1.4 percent of profits, plus $500,000 per year for the right to use Pueblo Viejo land, says Mr. Megías.

The company played informational videos and assured the Huave governing assembly that turbines are harmless, recall local leaders. But when the town appeared ready to vote it down, says one Pueblo Nuevo community member close to the negotiation who asked not to be named, Preneal warned that the crucial shrimping industry might be hurt if the company was forced back to plans to build in the lagoon. Preneal's Megías denies that was intended as a threat.

The town assembly then unanimously voted to allow a wind farm on town land. Money began flowing to the assembly, but none reached the people who will host the turbines, says Teodulo Gallegos Pablo, a fisherman and Pueblo Viejo village authority who votes in the town assembly. "There have been no payments [to the isolated community]."

Megías says Preneal paid the assembly but is not responsible for distribution of the money.

Mexican law requires "free and informed" consent for the land. But Mr. Gallegos contends that the people of Pueblo Viejo still don't know what they agreed to. Preneal promised that the turbines would only go on an isolated sandspit alongside fishing grounds – yet the contract clearly covers the whole island, and locals report that the company has taken soil samples in their fishing grounds.

"At first the people did agree," Gallegos says of his constituents. But not long after the contract was signed "some lawyers explained it to us and that's when the [Viejo] people stood up and said 'no.' "

The project is moving forward.

"The playing field is often very unequal," observes James Anaya, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

He likens land acquisitions in indigenous areas to colonial-era models of land grabs.

Looking at the Preneal deal in Pueblo Nuevo and Pueblo Viejo, he observes: "No Spanish or any other company would go to the bargaining table on a technical issue without their [own] technicians. And [yet] they expect indigenous people to."

Village vs. village

In other cases, the wind farms have exacerbated old rivalries.

Perhaps the most divisive and complex fallout from the wind farms is in Santa Maria and San Mateo del Mar – two Huave towns sharing a Manhattan-size peninsula.

For generations, the towns have feuded over a strip of land that Santa Maria owns but that the more traditional San Mateo con-siders sacred.

The village of San Mateo del Mar is renowned among archaeologists for the purest existing form of Huave culture: Women still weave and wear bright huipil (blouses), and men fish from land with nets connected to kites. Roman Catholic priests are expected to partner with the shamans, who worship natural forces, such as the wind.

When Santa Maria sold the rights to the contested land to build devices that harness wind, San Mateo snapped. Following a series of violent confrontations, San Mateo blockaded the only road to the mainland.

"They said they were going to starve us to death," says one Santa Maria farmer. It's not starving, but Santa Maria has certainly withered because getting in and out of the town now is only possible via a fearsome skiff-trip across heavy swells. To visit San Mateo, five miles away, Santa Marians must travel 70 miles by boat, taxi, and bus around the lagoon.

The Santa Maria village council says it needs wind turbines now more than ever. "The situation here is destitute," says Tarcio Jimenez José, a village leader. "There's nothing here.... The need forces us."

When asked about the local schism, Megías at Preneal blames it on the "violent leaders" in San Mateo. He said he was not aware of any religious role of wind, though his company published a book celebrating Huave culture and history.

Beatriz Gutierrez Luis, a San Mateo teacher and activist, says: "I understand this is supposed to be a form of clean energy. [But] if they gave us all the money in the world, we'd say 'no.' Our children and our grandchildren will depend on the fish, the shrimp, the love of the land, respect for nature, and all of our cosmology we have as an indigenous community."

Even so, the wind farm construction in Santa Maria is slated to go ahead, with turbines delivered by boat. Preneal will not do the work: It sold, for $89 million, the rights to the land in San Dionisio and Santa Maria to an Australian investment company and Coca-Cola bottling franchise. The partnership says the disputed land won't be developed.

Locals want control

Mexican wind energy capacity has grown fourfold in the past two years, to 500 megawatts. It has helped push Mexico's total renewable energy production to 26 percent of total electric output.

Most renewable energy here is provided by foreign companies. But a few locals are now trying to get into the game. Vincente Vasquez Garcia represents Ixtapec, a community just east of La Venta, which is attempting to create, manage, and profit from its own wind energy in partnership with a wind company.

"We cannot pass up this opportunity for our community," says Mr. Vasquez, who settled as an adult in Ixtapec and has energy sector experience. "But ... [w]e want a different kind of wind development."

The idea, he says, is for the wind farm to fund benefits such as better schools. Such models are emerging elsewhere, but without access to expertise, this is nearly impossible for largely illiterate communities.

Regardless of who builds them, wind farms are now a permanent fixture on the isthmus skyline.

"Before, no one knew who we were," says the La Venta restaurant worker. "Now, when I say, 'I'm from Oaxaca – you know, where the windmills are,' they know where I am from."