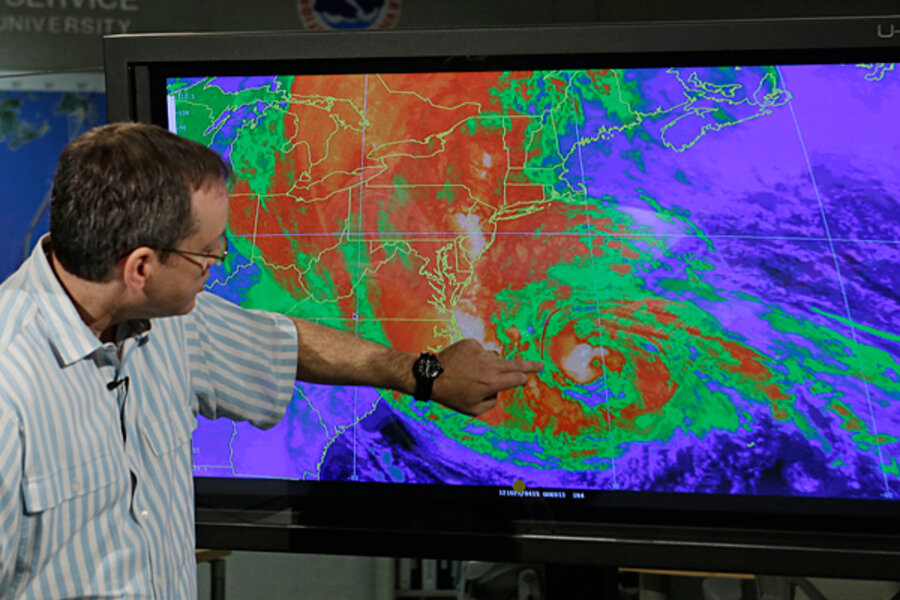

Hurricane forecast: Three to six 'major' storms could emerge this year

Loading...

The 2013 Atlantic hurricane season, which begins June 1, is shaping up to deliver above-normal activity again this year, according to several seasonal forecasts.

Indeed, the season could be extremely active, according to Kathryn Sullivan, acting administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Forecasters at the agency's Climate Prediction Center anticipate from 13 to 20 tropical storms over the six-month season. Of those, between seven and 11 are expected to become hurricanes, with three to six of the hurricanes expected to reach "major" status, meaning they host maximum sustained winds topping 111 miles an hour.

The federal forecast, released Thursday afternoon, brackets other seasonal outlooks that also point to a busy season.

In April, for instance, researchers at Colorado State University in Fort Collins released their initial forecast for 2013, which included 18 tropical storms, of which nine are expected to become hurricanes. Four could become major hurricanes.

That forecast, produced by Philip Klotzbach and William Gray, who pioneered these seasonal forecasts, is slated for an update June 3.

Meanwhile, forecasters at the commercial firm AccuWeather, based in State College, Pa., anticipate 16 tropical storms, leading to eight hurricanes that in turn could yield four major hurricanes.

The spread in NOAA's prediction for tropical storms is a bit wider than normal, Dr. Sullivan notes. It reflects "some uncertainty about whether the activity that will occur this coming season will be a smaller number of longer-lived storms or a larger number of shorter-lived storms," she said.

Broader atmospheric conditions present during the lifetimes of these storms will determine the difference – conditions that forecasters can't predict this far in advance, she notes.

While different approaches account for the differences among seasonal forecasts, they all are starting with some common basic ingredients.

Sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic are 0.8 degrees F. warmer than normal. "It might not sound like a lot, but that's quite a bit" above normal, said Gerry Bell, who heads NOAA's seasonal hurricane-forecast effort. Tropical cyclones draw their energy from warm surface waters.

Beyond ocean temperatures, "there's an entire set of wind and air-pressure patterns that come together to produce an active season," Dr. Bell said. "We've been seeing that entire set of conditions since 1995." Such conditions are said to go through 25- to 40-year cycles.

In addition, the Atlantic is feeling the long reach of conditions in the tropical Pacific. These currently reflect a state that some whimsically call "La Nada" – a climatological no man's land between east-west swings in sea-surface temperatures and atmospheric pressure known as El Niño and La Niña.

The swings take place in two- to seven-year cycles. When El Niño reigns, warm water migrates from the western tropical Pacific to the west coast of Central and South America. The change in air pressure that this warm water brings with it alters atmospheric circulation patterns in ways that stifle hurricane formation in the Atlantic.

With La Niña, El Niño's opposite, and La Nada, those stifling conditions vanish. This favors the formation of more tropical cyclones in the Atlantic.

Meanwhile, forecasters at the National Hurricane Center will have some new arrows in their quiver this year, which hold the promise of notable improvements in predicting a storm's path and intensity – in particular sudden changes in storm intensity. This is an issue that has bedeviled forecasters for nearly 20 years.

One of a forecaster's most palm-moistening moments comes when a storm unexpectedly intensifies just before landfall – leading to a last-minute change in the area covered by a hurricane warning. Likewise, forecasters want to be able to foresee rapid decreases in intensity, which can reduce the length of coastline under a tropical-storm or hurricane warning.

The Doppler radar on NOAA's P-3 Orion "Hurricane Hunters" can gather important clues that affect intensity forecasts. But until now, forecasters have had to wait until the planes land to get access to that information. With P-3 sorties lasting up to eight to 10 hours, the storm may have undergone significant internal changes during that time, with forecasters in the dark because they had no way of tapping the Doppler data as they were gathered.

Now, the planes have been outfitted with electronics that will relay information in real time.

"This is really, really big," Bell says.

The radar delivers information on storm structure from cloud base to cloud top, data on intensity, and in particular, changes in these features as the P-3s perform their reconnaissance flights. The data will get fed into an improved forecast model running on a new, more powerful supercomputer that will be ready for action in July – just ahead of the hurricane season's peak August-through-October period.

The new model has been running on research computers and in parallel with the operational model on an experimental basis for a few years. But the computer that forecasters currently use isn't powerful enough to handle the new model and the detailed data it must assimilate. The new computer is part of a larger upgrade under way to bring the National Weather Service's aged forecast computers up to modern standards.

Bell says forecasters expect to see a 10 to 15 percent improvement in intensity forecasts as well as in other aspects of hurricane forecasts when the new supercomputer is up and running and data from the P-3s stream in.