Clinton attributes hurricane Matthew's destruction to climate change. Is she right?

MIAMI — During a campaign rally in Miami Tuesday, Hillary Clinton said Hurricane Matthew was "likely more destructive because of climate change."

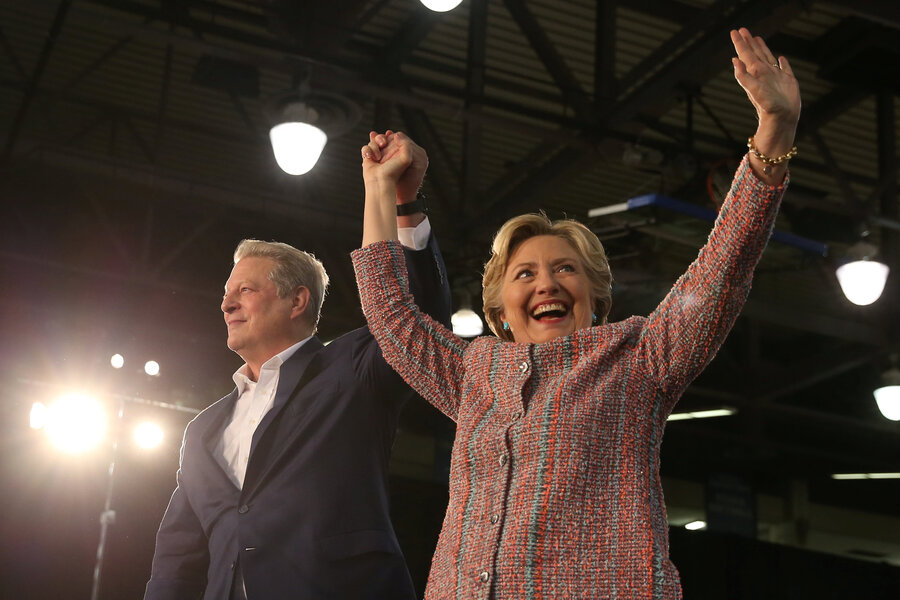

Clinton was campaigning alongside former Vice President Al Gore, who has become a leading climate change activist since leaving politics. She said near record high ocean temperatures "contributed to the torrential rainfall and the flash flooding" from the storm, particularly in the Carolinas.

Clinton also said that rising sea levels mean Matthew's "storm surge was higher and the flooding was more severe."

Matthew's death toll in the U.S. climbed to 30 Tuesday, half of them in North Carolina. More than 500 people are feared dead in Haiti.

THE FACTS: Clinton is generally right in a big picture way, but scientists who study hurricanes and climate change were not quite as comfortable when it comes to attributing significantly worse harm from a single storm like Matthew.

MIT meteorology professor Kerry Emanuel, an expert on hurricanes and climate, called Clinton's assessment "a simplification of the truth."

Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, said the signs of climate change are only seen in "the long-term average." Clinton's statement, he said, was "a little bit strongly worded for a single event."

But as for the storm surge being worse, Emanuel called that a "no brainer" because sea level is higher.

"The same storm in terms of a wind and pressure event 50 years ago would have produced a lower surge because sea level is lower," said Emanuel, who was a registered Republican from 1976 till about seven or eight years ago.

McNoldy noted the differences are small.

"If Matthew had occurred 20 years ago the storm surge instead of being 8 feet might have been 7 feet 9 inches," he said.

To a person whose house was flooded, those three inches might not have been noticeable, McNoldy said. But an extra three inches for someone on the edges of the surge could have made the difference between staying dry and getting any water in the house.

Hurricanes use warm water as fuel and the water in the part of the Atlantic that Matthew was in was about 1.8 to 2.7 degrees warmer, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And that means more potential rain, Emanuel said. So does warmer air.

Warmer air holds more water — about 7 percent more for every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit — and "you get more heavy rains with more moisture," said Mark Boslough, a Sandia National Lab physicist who works on climate change.

"Matthew no doubt rained more than an identical storm would have 30 or 40 years ago because it is warmer," Emanuel said. He said Matthew intensified incredibly fast — an additional 3.5 mph per hour — and studies have shown that in general "rapid intensification becomes somewhat more likely as the climate warms," Emanuel said.

But McNoldy said that extra fraction of an inch of rain may not have been that big a deal. In general, he said Matthew's strike on the U.S. — not Haiti —was not that exceptional, even quite average for a hurricane.