Antarctica rift: Larson C ice shelf close to becoming huge iceberg

Loading...

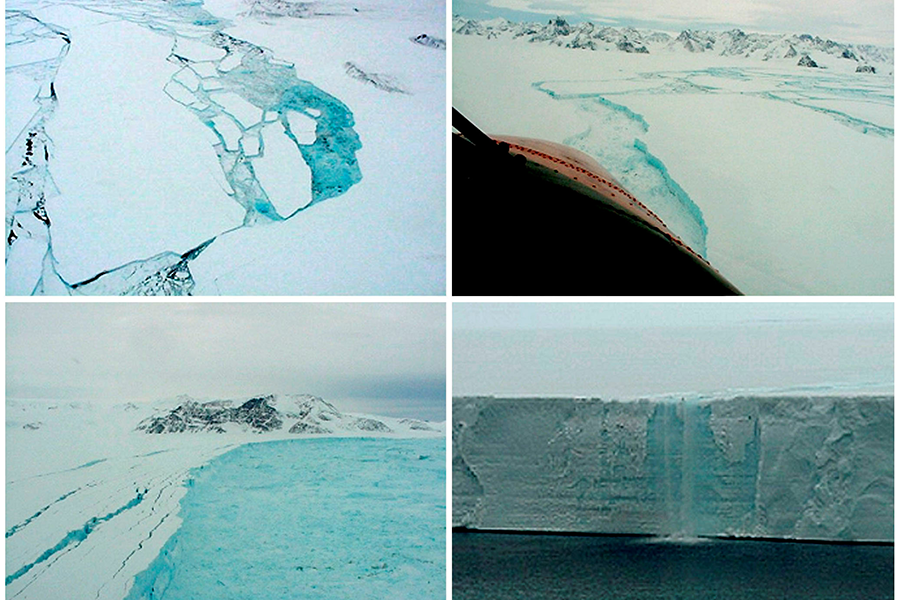

Scientists with the British Antarctic Survey now believe that the fracturing of the Larson C ice shelf from the polar cap is imminent, after a rift in the shelf grew vertiginously in the last month of 2016.

The thread connecting Larson C to the rest of Antarctica is now just more than 65,600 feet long, surveyors from the Britain’s Project Midas say.

"If it doesn't go in the next few months, I'll be amazed," project leader Adrian Luckman, from the University of Swansea in Wales, told the BBC, adding that "it's so close to calving that I think it's inevitable."

When it does, says Dr. Luckman, the iceberg it will likely form could be among the top 10 biggest icebergs ever recorded. Andrew Fleming, remote sensing manager at the British Antarctic Survey, told Reuters that the ice was being thawed by a combination of warmer air above and warmer waters below.

Researchers say there’s no evidence yet directly linking the collapse to climate change. But the apparent imminence of the event puts the spotlight on how it might affect global sea levels, an issue entwined with hazards to human habitation. And it comes as new research suggests that changes in the ocean around Antarctica mirror conditions from 14,000 years ago that led to a rapid melting of the ice sheets and a 10-foot rise in global sea levels.

At the end of the last Ice Age, a team of Australian and New Zealander climatologists wrote in a study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports, the ocean around Antarctica divided in much cooler and warmer layers.

A similar dynamic is happening now, the study found. As global warming melts land-based ice, cool fresh water flows into the ocean surface, leading to more extensive sea ice.

"At the same time as the surface is cooling, the deeper ocean is warming, which has already accelerated the decline of glaciers in the Amundsen Sea Embayment," lead author Chris Fogwill told the University of New South Wales’s newsroom. "It appears global warming is replicating conditions that, in the past, triggered significant shifts in the stability of the Antarctic ice sheet."

The Larson C’s collapse won’t directly contribute to rising sea levels, notes the survey in a press release. But ice shelves, which are floating extensions of glaciers on land, hold back huge volumes of ice that enter the ocean and raise sea levels, as happened in 1995 when the Larson A ice shelf broke off and again in 2002 with the collapse of the Larson B shelf.

"The Larsen B shattered like car safety glass into thousands and thousands of pieces. It disappeared in the space of about a week," Dr. Fleming told Reuters.

Given expectations of the collapse, the Survey has chosen not to camp out on the ice this season, as they usually do to monitor the sea floor beneath the ice shelf. Instead, they’ve been using images provided by European Sentinel satellites.

"These images are perfect for following these changes since they provide detailed information, day or night and regardless of cloud cover," Fleming said in the release.

This report contains material from Reuters.