Hands-on learning is best for understanding energy issues, study finds

Loading...

In June of 2013 UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon called on youth around the world to take action to address climate change. What better way to confront environmental problems than to get our future leaders to act? And the first step in taking action is education. If children don’t understand the issues, they won’t be able to solve them. But how do we teach youth the complex issues facing our energy challenges?

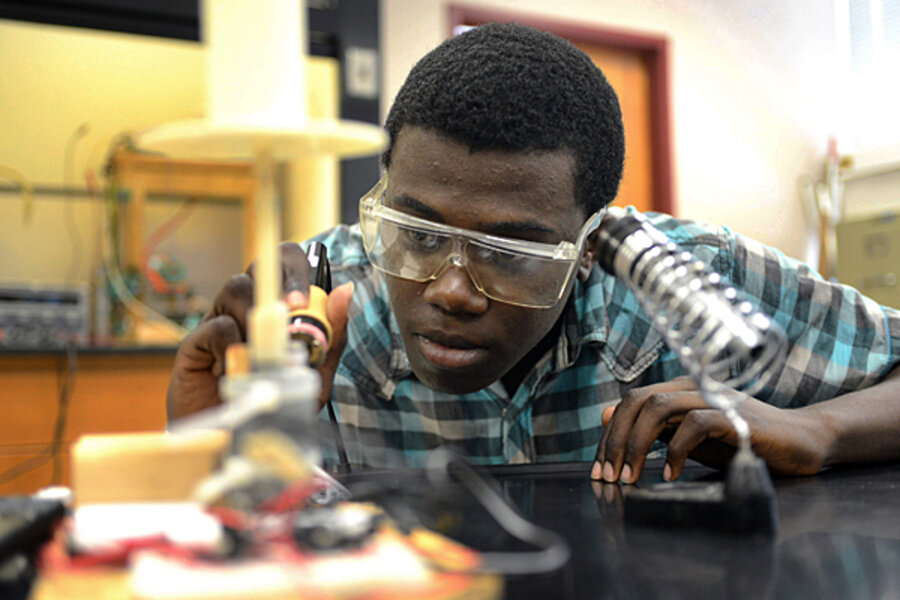

Forget about lectures and spreadsheets. A Purdue University study found that the best way to get students engaged is to focus less on textbooks and more on interactive, problem-solving design projects. There are many innovative programs around the world that are teaching students about climate change and energy issues through hands-on education.

PROJECT-BASED LEARNING

The Solar Schoolhouse is a K-12 energy education program developed by the Rahus Institute in 2001. The program introduces students to the concepts of solar energy through hands-on, project-based teaching tools. Besides lesson plans that can be integrated into existing school curriculum, Solar Schoolhouse offers project plans and resource kits so students can build solar cookers, solar chargers, solar fountain sculptures, and even a solar boom box.

Solar Schoolhouse also trains teachers in how to offer these hands-on projects to their students. In a recent teacher training, 30 teachers from the Oxnard, California, school district learned how to assemble the components for a solar cell phone charger. “This involves the students doing higher-level thinking, more project-oriented learning,” says George Naugles, a seventh-grade teacher from Fremont Intermediate School. “We’re hoping this hands-on kind of project will be the new bread and butter for our science curriculum.”

SOLAR RACE CARS THE KEY TO GETTING TEENS EXCITED

Energetics Education is an organization that spun off from Solar Energy International’s Solar In the Schools program. Energetics Ed’s flagship program is Solar Rollers, which teaches high school students how to design, build, and race sophisticated solar-powered remote control cars. “There is nothing more important than teaching energy-based climate change solutions to young people,” Energetics Ed’s founder Noah Davis told RMI. “Except for making this learning process positive and fun.”

Energetics Ed wanted to fill the gap between the Junior Solar Sprint, a middle school drag race using small solar cars with preassembled solar panels and no electronics, and the American Solar Challenge, a university-level competition with full-scale solar cars raced by drivers and designed by large teams of engineering students with exceedingly high budgets.

Solar Rollers gives high school students a valuable opportunity for deep, engaging hands-on learning. Teams tackle a complete energy system, from harvesting sunlight to energy storage to efficient energy use. Through the process of designing, building, testing, refining, and eventually racing their solar-powered cars, students learn about energy efficiency, solar electricity, motors, batteries, material properties, gearing, friction, and more. They actually solder solar cells together to make a small array, not a simple task. “Every time you hear something crack you freak out,” says Robinson Meng, a high school junior who built a solar roller. But the hard work is definitely worth it. “This is going on my resume,” adds Meng.

VISUALLY REPRESENTING ENERGY

Once kids understand energy, how do they take that knowledge to the next step? Across the Atlantic, there are groups working on educating youth to design a sustainable energy future. Energy Crossroads Denmark has developed a game that has been used all over Europe to teach youth how to create their own future energy scenario for 2030.

Energy planning has historically been a discipline for people who understand the complicated models and are able to juggle all the thousands of figures and energy units in the debate. Changing the Game is designed to demystify the energy planning and policy development process by making things as visual as possible. They do this by translating words and numbers into a visual representation expressed in LEGO bricks. Each brick represents a given amount of energy, and the color of each brick indicates the type of energy resource. Black = coal, green = biomass, blue = hydropower, yellow = solar, etc. Furthermore the CO2 emissions of the fossil fuels are shown through the width of the bricks.

The original game takes two days to play, and at the end the participants have a carefully considered and practical plan for Europe’s energy future to 2030. A shorter four-hour version has been successfully played in universities and at organizations—reaching the same goal, but with less emphasis on the policy impacts throughout the society. A shorter two-hour version was developed for use in high schools, and by the end of 2012 had been played by over 4,000 students throughout Denmark.

A group from Singapore found the game so informative they developed a version for Southeast Asia. Another enthusiastic supporter carried 1,000 LEGO bricks with him as he bicycled across Africa so he could hold Changing the Game workshops at schools and universities along his route.

There are numerous other school districts and individual teachers who are coming up with exciting ways to teach children about energy. Students involved in hands-on learning, as was shown in the Purdue study, demonstrate a deeper understanding of the issues. “This is a significant finding,” says Melissa Dark, an assistant dean involved in the Purdue study, "because it proves that with some students—especially groups traditionally underrepresented in science and engineering—the book-and-lecture format may not be the best way to engage students in learning."

Taking the hands-on learning concept and using it to teach students about climate change and the energy issues confronting us today is a key step in getting our future decision-makers to make smart decisions. “Young people have the adaptability, the motive, and a lifetime of opportunity to make meaningful changes in society's energy systems,” Noah Davis, founder of Energetics Education, explained to RMI. “They need only to understand those systems and find the confidence to move ahead.