Do uranium mines belong near Grand Canyon?

Loading...

| GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK, ARIZ.

On a ragged outcrop just a short walk from a Grand Canyon overlook where millions of visitors annually come to gawk at one of the world’s most stunning vistas sits the old Orphan uranium mine. Soil radiation levels around it are 450 times higher than normal. It’s encircled by a protective fence.

A sign warns: “Remain behind fence – environmental evaluation in progress.” In the canyon hundreds of feet below, another sign by gurgling Horn Creek instructs thirsty hikers not to drink its radioactive water.

Even so, Horn Creek eventually splashes its way to the canyon bottom and into the Colorado River, a vital water source for 25 million people from Las Vegas to Los Angeles to San Diego. In that mighty river, the Orphan’s radioactive dribble is diluted to insignificance.

But what if a dozen or even scores of new uranium mines were leaching uranium radioisotopes into this critical water source? That is what Arizona’s governor, water authorities in two states, scientists, environmentalists, and Congress are all worried about. Should they be?

Everybody from mining-industry officials to environmentalists agrees that the Orphan mine is a poster child for the bad old days of uranium mining going back to the 1950s. Today’s regulations and newer mining techniques make such pollution far less likely, industry officials say, though environmentalists vehemently disagree. The question remains: Is Orphan only a vision of the past – or is it a vision of the future, too?

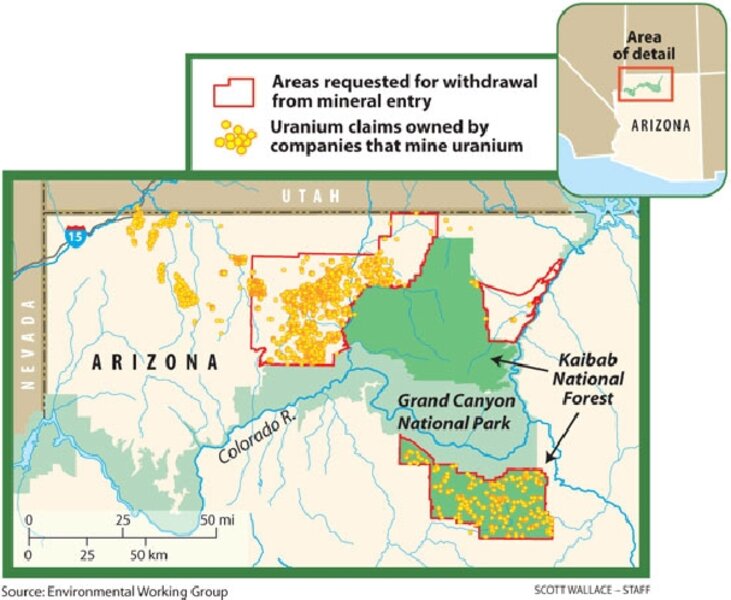

The US Southwest may be about to find out. Driven by soaring uranium prices and fresh interest in nuclear power, mining companies have staked more than 10,600 exploratory mineral claims – most of them smaller than five acres – spread across 1 million acres of federal land adjacent to the Colorado River and Grand Canyon National Park, a federal official told Congress in June. Most are uranium claims, though some may be for other metals, observers say.

Such numbers and testimony about pollution have begun to move Congress. Following congressional hearings, the House Natural Resources Committee in late June declared an emergency withdrawal of 1 million acres from any mining claims. The federal land in question is on the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon, just outside the national park, through which the Colorado River flows.

While a federal lawsuit and injunction have temporarily stalled uranium development in the national forest on the south rim, Congress’s action is being resisted by the Bush administration on the north rim.

There, lands controlled by the Bureau of Land Management are unaffected by the lawsuit to the south and exploration claims are still being processed routinely.

One such claim, by Quaterra Alaska Inc., the US subsidiary of Vancouver-based Quaterra Resources, Inc., was approved for exploratory drilling on June 27 – just two days after the House’s Natural Resources Committee vote that should have stopped such action.

A Department of Interior spokesman says the BLM is still processing claims because the agency doesn’t consider the Congressional vote valid. In a July letter it argued that the committee didn’t have a quorum, a point disputed by the committee’s chairman and the House parliamentarian.

Mining regulations are tougher now

“They are charging forward,” says Taylor McKinnon, public lands director for the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental group based in Tucson, Ariz.

Last month, the US Department of Energy approved 42 square miles for an expanded uranium mining program in the watershed of the Dolores River, a tributary of the Colorado. But the question of what impact dozens of new uranium mines across the entire Colorado River watershed might have – an environmental disaster or an energy bonanza with few ill effects – remains hotly debated.

“Old mines like the Orphan were mined in the 1950s under no federal regulations whatsoever,” says Eugene Spiering, vice president of exploration for Quaterra. “Most mines today are above the water table, which makes chances of leakage practically nil. What we have now is a well-regulated industry.”

Still, there has been no regionwide environmental assessment of the likely impact of a new uranium mining boom on the Colorado River, close observers say. Nor is such an evaluation apparently of much interest to federal land managers, if comments on the subject by a Department of Interior spokesman are any guide.

“We already have the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and others that require comprehensive analyses before any mining is done, so there won’t be impacts to the environment,” says Chris Paolino, a spokesman for the Department of Interior. “At this time we’re still evaluating plans on an individual basis, but [a regional study is] not something I can rule out.”

“We hear from the industry and federal government that today ‘we can do it safely,’ ” says Roger Clark, air and energy director for the Grand Canyon Trust, an environmental watchdog group. “But the burden of proof is on the proponents. Somebody needs to ask, ‘What is the cumulative threat to drinking water in the Colorado River – not just from radioactivity, but from arsenic and mercury from these mines?’”

Some are asking for exactly such a study. With cities like Phoenix relying on clean Colorado River water, Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano (D) is calling for an “overall environmental impact analysis,” citing the uranium boom’s “potential to seriously harm” the water quality of Grand Canyon National Park and the Lower Colorado River.

Uranium company officials say fears about radioactive contamination are overblown. New mining methods, far tougher environmental standards, and desert-dry conditions for most mines mean minimal risk to the Colorado River and the region’s precious groundwater resources, they say.

“Yes, there were issues in the past,” says Ron Hochstein, president of Denison Mines, a Toronto-based company with at least nine mines under development in the area targeted by Congress. “But that’s not the way we do things today. We understand and know a lot more about uranium, radium, and radon and the impacts of those. So to say some things that happened in the 1950s and 1960s will happen again today is not a good comparison.”

Proven deposits are likely to be mined

Whether or not the thousands of unproven claims are ever developed, a fair number of uranium mining sites seem almost certain to reemerge. “Congress’s action only applies to unproven claims,” Mr. Clark points out, leaning against a fence at the Canyon Mine site.

Denison’s group of established mine sites – including the Canyon Mine in the Kaibab National Forest a few miles south of the park – are among those likely to reemerge. The Canyon Mine was mothballed in the 1980s – before it had even opened – because of sinking uranium prices. It is a proven site: Uranium is there. Denison must still apply for new state environmental permits in order to proceed, but expects its mines to begin opening around 2010.

Despite Horn Creek pollution, the good news is that recent studies have shown that most springs and creeks in the Grand Canyon still have good water quality: Uranium and other trace metals appear in low concentrations, according to congressional testimony.

The bad news, experts say, is that digging into the cylindrical vertical rock formations in which uranium is found – they’re called “breccia pipes” – can “mobilize” the uranium, causing it to oxidize when water from periodic downpours seeps down through the rock strata.

Indeed, the negative impact of water on uranium mines should not be minimized even in the desert, says Chris Shuey, a scientist who directs the Uranium Impact Assessment Program, a nonprofit research and information center. His research in the Churchrock area of the Navajo Nation near Gallup, N.M. – where uranium was mined and processed between 1952 and 1983 – showed statistically significant effects on human health from the elevated levels of radioactivity in the region.

While much uranium in the region does occur in formations above the water table, the bottom of the breccia pipes are located in the upper portion of the Redwall Limestone, a principal aquifer supplying springs in the Grand Canyon and wells for much of the region, Dr. Shuey told Congress in March.

“When you take uranium and the other trace elements out of their resting places in nature and expose them to the environment,” Shuey says by phone, “you expose them in higher concentrations to the environment and intensify their effects. People don’t appreciate the cumulative impact of mining in a consolidated area. There’s a very real threat.” A flash flood swept through Havasu Creek last week. That same watershed includes the Canyon Mine and numerous uranium claims.

Abe Springer, a hydrologist and researcher at Northern Arizona University at Flagstaff, has made a career studying the movement of groundwater through the Redwall and other aquifers into seeps and springs that supply not only hikers, but also most of the region’s animal life with the water they need to survive.

“Once these elements became mobile through mining activities,” Dr. Springer told Congress in his March testimony, “they would continue to be mobile through the aquifer and eventually discharge in springs impacting the human uses of water of these springs.”

Even so, some industry figures dispute any connection between the Orphan uranium mine and higher radiation in Horn Creek.

A “fact sheet” e-mailed by Quaterra’s Mr. Spiering says, regarding water pollution, that “statements that the historic operations at the Orphan Mine have been polluting Horn Creek are false.” It cites a 2004 US Geological Survey study showing dissolved uranium in a range from 8.6 to 29 parts per billion and “within the EPA levels of safe drinking water.”

Closer look at USGS study

But a closer examination of the 2004 results finds that some uranium concentrations are at the upper end of the safe range for Horn Creek.

The same study’s results for nearby Salt Creek (at 29 to 31 p.p.b.) “approached or exceeded the US Environmental Protection Agency’s drinking water standard” of 30 p.p.b., according to Shuey’s testimony to Congress.

The two creeks – Salt and Horn – also had by far the highest levels of the 20 springs and seeps tested in that study, Shuey testified. That USGS study also did not seek to assign causes of the higher radiation levels, he noted.

But the potential impact of tainted groundwater on native Americans, hikers, and local wildlife – as well as major cities downstream – are all reasons Rep. Rául Grijalva (D) of Arizona has sponsored legislation to permanently withdraw federal land around Grand Canyon National Park from uranium mining.

“I hope we’ve matured enough not to forget history,” Representative Grijalva says in a phone interview. “Protection of water quality in the Colorado River is vital to the long-term health and safety of humans and other species. We can’t afford to simply issue permits and decades from now simply dismiss the consequences as unintended.

“We should know better than that.”