Climate change as art

Nathalie Miebach, at first impression, could almost be mistaken for a toymaker. Her studio in Boston's South End is a swirl of beads, tiny whales, flags, origami birds, and spokes of bright colors. Musical scores line the walls. Reedy sculptures sprout from the floor and dangle from the ceiling. Tinkertoys come to mind – as does the Mad Hatter.

But behind the joyful chaos is a precise order, one of surprising complexity and magnitude. Ms. Miebach creates art by translating weather data into baskets and sound.

Scientists struggle to make sense of statistics about climate change, even as political battles rage over their conclusions. Miebach aims for observation, not answers. Her innovative work focuses on the places where science and art intersect, fueling the imagination without straying from the limits of recorded data. As a result, despite their complexity, her visual and audio renditions of meteorology evoke childlike wonder from what was once a heap of numbers.

"Using this kind of toy language is really useful in disarming the viewer," says Miebach of her colorful, yet careful work. "Scientific data can be very intimidating. The playful elements [of the pieces] are designed to lure you in and then you realize this is all based on numbers."

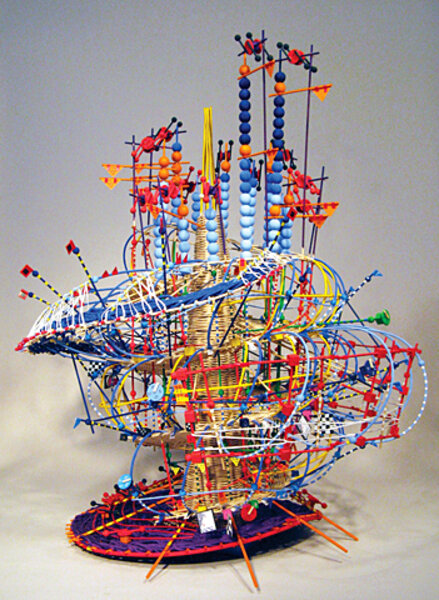

Consider "Hurricane Noel," the name for both a free-standing sculpture and a musical score based on the wind, temperature, and barometric pressure of hurricane Noel as it entered the Gulf of Maine in November 2007.

The sculpture, standing about three feet tall, has a conical center, with spokes framing a specific time period of the storm's cycle. Working vertically, temperature is translated into red. Barometric pressure is green. Wind speed is blue, and so on. As Noel's recorded numbers – pulled from a weather station in Hyannis, Mass.; a buoy in the Gulf of Maine; and a weather station in Natashquan, Quebec – rise and fall through the hours, the colored reeds warp to form the sculpture's shape.

With the musical score, Miebach assigned each element an octave and each temperature a pitch. Collaborating musicians from Axis, a contemporary classical ensemble, took her score and composed a 15-minute symphonic storm for piano, violin, accordion, clarinet, cello, and double bass. Their only requirement from Miebach: Stay true to the numbers.

"We had to create the piece so that it actually represented the form of the hurricane" while still being pleasing to the audience, says Phil Acimovic of the Axis ensemble. They performed "Hurricane Noel" at the Lily Pad in Cambridge, Mass., in March.

It hasn't always been science for art's sake. Miebach originally sought to use art as a way to articulate climate change. One of her installations was based on NASA's ozone hole data. Using stacked sheets of tracing paper with a cutout center to represent one day in the polar region, Miebach built 3-D models of the hole representing two-month periods over 10 years. That work, which was exhibited in the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Mass., revealed not a linear progression of the breakdown of the protective gas but a "pulsating being that is contracting and expanding all the time," says Miebach.

The idea for combining scientific data and art emerged for Miebach in 2000. She enrolled in a community basket-weaving class and a Harvard University astronomy course at the same time. Studying images of stars felt far removed from the tactile experience of weaving. To reconcile this, instead of a final astronomy paper, Miebach turned in a basket that depicted the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, or the life span of a star. "I had a very open-minded professor," jokes Miebach.

Between 2006 and 2008, she spent two seven-month stints on Cape Cod at the Fine Arts Work Center recording and observing the elements. As she did so, her focus shifted. Instead of viewing weather through "the lens of climate change," she strove to understand it "on its own terms," she says. Meibach eventually relied less on her scientific instruments and more on her peripheral sensory observations, the key, she feels, to understanding complex relationships.

As she began to experience and translate the interplay of the wind, the water, the sand, and even the birds Miebach incorporated toylike visuals into her work. Now she spends time in toy stores, mining for more ideas to engage viewers.

"The first time I saw Nathalie's 'Gulf of Maine' [wall sculpture] I just wanted to lie down on the floor and stare at it for hours," says Amy Holt Cline, a marine-science teacher who taught a high school course about the Gulf of Maine in Gloucester, Mass. "Art is a perfect tool to understand science better because students need to be able to see their ideas in 3-D" and not just as computer images.

In order to push the limits of her own weather "language" of basketry, Miebach seeks new perspectives and audiences for her data, including those of scientists.

"Specification has eradicated a sense of playfulness in discovery," says Brian Knep, an artist in residence at Harvard Medical School who invited Miebach to present her work there. Mr. Knep frequently brings in artists working with scientific data to lecture as a way to engage different viewpoints.

"When [the scientists] meet these artists ... they say 'I want to do that,' " says Knep. "They just want the freedom to explore."

Miebach says she is now content to stay in the questions presented by weather data instead of trying to resolve their scientific meaning.

"What is wind? You could spend a lifetime answering that question," says Miebach. "There is a lot of beauty that can come out if you allow that question to linger."