Why Gioachino Rossini's music is so funny

In 1822, hotshot opera composer Gioachino Rossini got a bit of advice from Ludwig van Beethoven: Stick to comedy. At age 30, Rossini was already an international superstar, with nineteen operas under his belt, when he met the crotchety, near-deaf German composer in Vienna.

"So you’re the composer of The Barber of Seville." Beethoven said. "I congratulate you. It will be played as long as Italian opera exists. Never try to write anything else but opera buffa [comic opera]; any other style would do violence to your nature."

Rossini politely reminded Beethoven that he had already written several well-received serious operas; he had even sent them to Beethoven for a look. "Yes, I looked at them," the old man retorted. "Opera seria is ill suited to the Italians. You don’t know how to deal with drama."

Beethoven’s words turned out to be eerily prescient. Rossini was renowned for his dramatic work during his life, but those historically fell by the wayside in favor of his comic operas, chiefly "The Barber of Seville." Later use of Rossini’s works in cartoons, commercials, and sitcoms further cemented his reputation as one of the opera world’s great comic minds. His 220th birthday (or 55th, since it’s a leap year) is today.

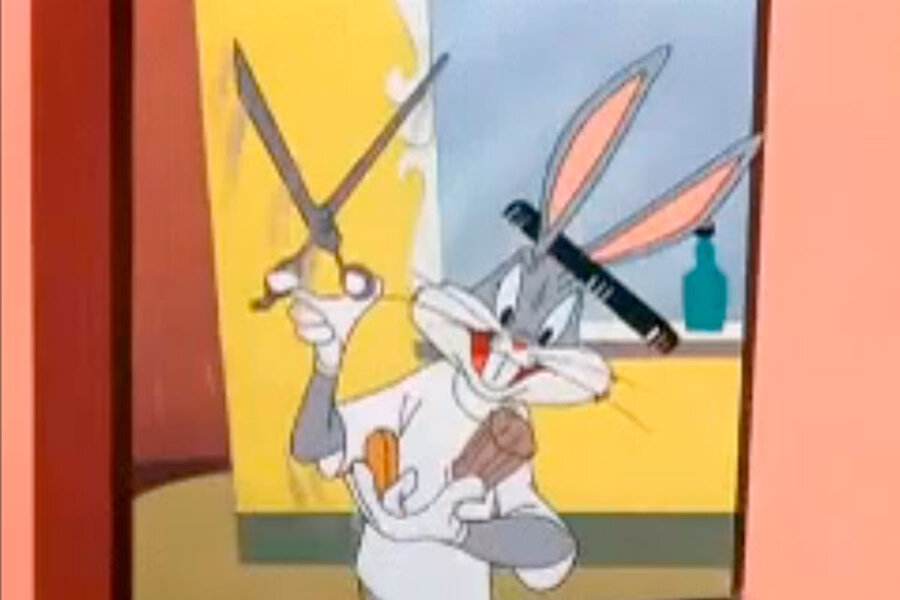

If you own a TV, chances are you’ve heard Rossini’s music. His "William Tell" overture has been used in countless commercials, cartoons, and sitcoms (think galloping horses, or any race scene). "The Barber of Seville, " praised by Beethoven was immortalized in cartoons, most notably the classic "Rabbit of Seville" episode of Looney Tunes.

"His pieces each have a very broad character and a distinct personality. This makes them perfect for cartoons," says musicologist Steven Ledbetter. He points to the four distinct sections of the William Tell overture. "You can hear that and say, oh, that’s perfect for a day in the country, or a storm scene, or a day at the races."

Adding to the comic potential for Rossini’s work may have been the personality of the man himself. According to Dr. Ledbetter, the prolific composer had a finely tuned sense of humor and was, in himself, a very funny man. "For one, he was unbelievably lazy. He liked to compose while lying in bed or chatting with his friends."

According to one legend, Rossini once dropped a piece he was working on, and in lieu of getting out of bed to retrieve it, started over. When a friend fetched the dropped music for him, he turned that into a completely different piece.

Despite this, he completed an average of four operas a year during his formative composing years, some in as little as two weeks. "Writing opera was really like writing sitcoms in television today," Ledbetter says. "The style involved little emphasis on the orchestra and mostly focused on keeping the singers happy. Rossini was a wonderful singer, so he knew how to do that."

In pleasing his singers, Rossini created character types and scene structures that can to pervade comic opera, as well as Bel Canto opera in general. One of his frequently appearing character types is a "patter baritone," a man who spits out words at breakneck speed in a hilarious yet impressive display of vocal agility. In "Barber" it’s the character Figaro, who complains of the multitudes of people begging for his services in the famous "Figaro aria."

"The way it piles up, plus sheer speed of it, is really funny," Ledbetter notes.

Rossini, too, was one of the fathers of the frantic Act I finale now common in stage productions of every stripe. You can spot it in sitcoms, too. "In the first act, things are constantly changing, dragging on, and getting, more complicated and more frantic," Ledbetter says. "By the end, everyone is running around like crazy. Then in the second act they solve everything. Rossini took that idea and made it a formula."

In his early years, Rossini didn’t focus much on orchestrations, probably because they are more time consuming and complicated to write than vocal lines (lazy). But when he did, he was cognizant of the opportunities for humor there as well. "He is very careful about how he uses instruments," says Phillip Gossett, a professor emeritus of music at Chicago University, and one of the leading scholars on Rossini. "In the Barber overture, for instance, he uses a bass drum. Then we don’t hear bass drum again until the middle," in a moment of perfect comic timing. Frequent use of the crescendo technique, where the music gradually builds in volume and speed to a climax, was another Rossini calling card, earning him the nickname "Monsiueur Crescendo" during his career.

"[Barber] has a sense of laughing at itself and the whole genre, " Dr. Gossett adds. "Great fun within the opera taking advantage of techniques that are characteristic of opera and using them pointedly. There’s a self irony there, and he’s very aware of it."

As a result, filmmakers and commercial directors have mined Rossini for comedy countless times. For instance, "Seinfeld" and "Curb Your Enthusiam" creator Larry David is a frequent Rossini user: The Seinfeld episode "The Barber" is scored entirely from the opera.

But Rossini wasn’t all laughs: At the height of his fame, he was better known for his serious operas, most of which faded entirely into obscurity until very recently, owing mostly to the popularity of his later contemporaries, Verdi and Wagner. Their work was weighty and genre-bending, making Rossini’s tragedies seem safe and outdated by comparison. In 1816, Rossini wrote an operatic adaptation of "Othello," for example, that had a happy ending, which hewed to the formal constraints of opera at the time. When Verdi wrote his Othello some 70 years later, the ending was true to Shakespeare.

So, is Rossini’s comic reputation fair, or should he be regarded in a more serious light?

"I don’t think we want him to recover from it," says Gossett. "I want him to get credit as more complex, but I don’t want him to recover because it’s very funny, and it functions extremely well."

For more on how technology intersects daily life, follow us on Twitter @venturenaut. And don’t forget to sign up for the weekly BizTech newsletter.