Can digital privacy exist when life online is public by nature?

Loading...

Is privacy possible in an increasingly interconnected world? Experts aren’t particularly optimistic – in a new poll conducted by the Pew Research Internet Project, 55 percent of Internet and security experts predicted that policymakers and technologists would not be able to create a basic, unified privacy-rights infrastructure by 2025.

The poll encompasses 2,511 responses from experts on security, privacy, and freedom in the online world, many of whom said that online life is public by nature, and that upcoming generations will not value privacy the same way current generations do.

“In order to ‘exist’ online, you have to publish things to be shared, and that has to be done in open, public spaces,” writes GigaOm lead researcher Stowe Boyd as part of the poll results, adding that people give up a certain amount of privacy in order to find friends and conduct business online.

The poll’s respondents also noted that many popular businesses and services rely on the capture of personal information as part of their business model. Tech companies such as Google and Facebook aggregate user information to sell to advertisers, who then create targeted ads based on demographic information and browsing habits. Traditional retail, entertainment, and insurance companies are also relying more and more on the capture of user information as part of their business models.

Most respondents also agreed that people are generally willing to give up personal information simply for the sake of convenience.

“[M]ost people’s life experiences teach them that revealing their private information allows commercial (and public) organisations to make their lives easier (by targeting their needs), whereas the detrimental cases tend to be very serious but relatively rare,” writes Bob Briscoe, a chief researcher for British Telecom, in the survey.

It’s worth pointing out that the survey was not necessarily a representative sample of expert views: Pew refers to their method as a “canvassing,” since the organization invited experts to weigh in on the question rather than conducting a randomized, controlled survey. Nevertheless, most respondents agreed that while online life is public by nature, an international privacy framework is needed to ensure security and continued innovation.

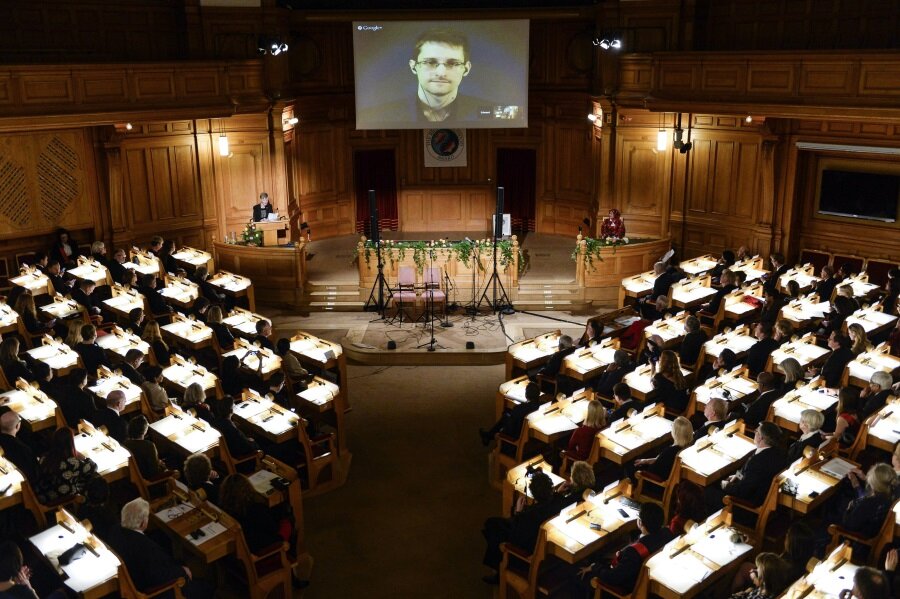

Last month the United Nations approved a resolution that would call on member states to protect citizens’ right to online privacy. Sponsored by Germany and Brazil, the “Right to privacy in the digital age” resolution follows on a similar measure calling on states to respect human rights online. The latter resolution passed after former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked information about surveillance practices in the United States and elsewhere.