How white roofs shine bright green

Loading...

Can you help save the planet by painting your roof white?

Hashem Akbari thinks so.

Global warming’s complexity and momentum have led to a try-everything approach by scientists. In that spirit, Dr. Akbari offers his simple yet profound innovation for slowing that warming way down.

It has long been known that a white roof makes a dwelling cooler. That saves energy and cuts carbon emissions. But until Akbari, a researcher at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, picked up a pencil to do the calculations, few realized the major climate effect that millions of white rooftops could have by reflecting sunlight back into space.

It turns out that a 1,000 square foot area of rooftop painted white has about the same one-time impact on global warming as cutting 10 tons of carbon dioxide emissions, he and his colleagues write in a new study soon to be published in the journal “Climatic Change.”

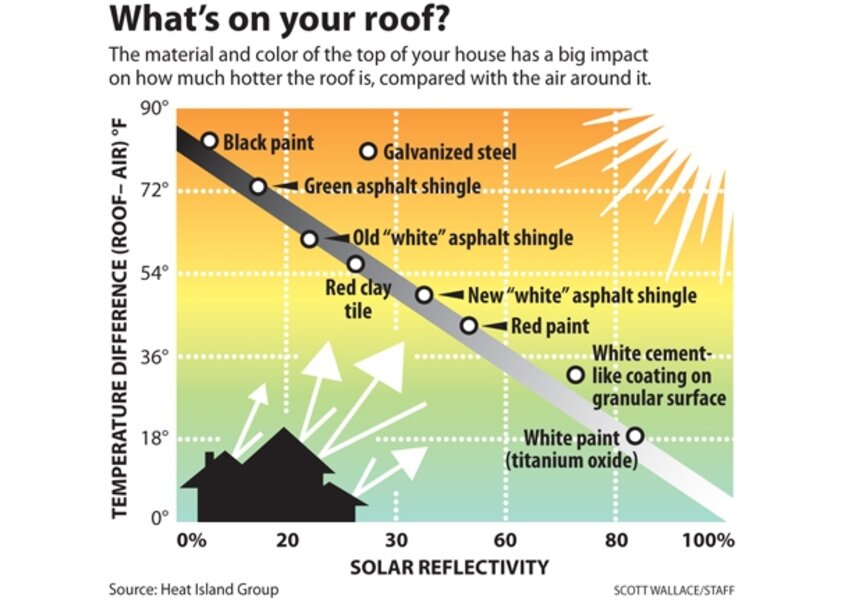

As sunlight pours down into Earth’s atmosphere, some of the energy is filtered out or bounces off clouds. About half the energy shines through as visible light and some of that hits the tops of houses. If a roof is white, most sunlight reflects back into space and doesn’t heat the earth. But if a roof is a dark color, the sunlight converts to heat rather than bouncing off as light. That thermal energy then radiates off the roof back toward space, where it is trapped by CO2 in the atmosphere, and then absorbed by this greenhouse gas. As a result, the world’s thermometer reads just a little higher than it did before.

If the estimated 360,000 square miles (less than 1 percent of the world’s land surface) covered by urban rooftops and pavement were a white or light color, enough sunlight would be reflected back into space to delay climate change by about 11 years, the study shows.

Put another way, boosting how much urban rooftops reflect, called albedo (al-BEE-doh) in scientific terms, would be a one-time carbon-offset equivalent to preventing 44 billion tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere, Akbari says. It’s about the same as taking all the earth’s automobiles off the road for 11 years, the study’s authors say.

“What we have done are very simple calculations,” Akbari says, “but it is novel because, for the first time, we’re equating the value of reflective roof surfaces and CO2 reduction. This does not make the problem of global warming go away. But we can buy ourselves some time.”

Selling the idea

Geoengineers have had similar ideas: covering the Sahara with enormous sheets of white plastic, for instance, or painting the Black Hills of South Dakota white.

But because white roofs create an additional 20 percent energy savings by cutting cooling costs, some say this built-in financial incentive should propel urban rooftops around the globe to lighten up.

“Now that we know what a great help it is on climate change, we expect more utilities to give incentives for homeowners who go entirely white with their roofing material, not just ‘cool’ colors [like pastel blues, reds, and greens]” says Arthur Rosenfeld, a member of the five-person California Energy Commission.

To promote energy efficiency, Georgia and Florida already give incentives to owners who install white or light-colored roofs. Going a step further, California has since 2005 mandated that all flat roofs (mostly commercial and industrial) must be white. Some utilities also now offer homeowners an incentive of 20 cents per square foot on a tile roof that may cost $1.20 a foot.

Still, the cost of going with a “cool roof” usually isn’t much more than a typical darker roof. Asphalt shingles with a white or light tint are roughly the same cost as other shades.

Painting a black asphalt roof with the reflective white coating, however, is obviously more expensive than the black surface alone. But energy savings largely offset the price of painting through reduced air conditioning costs, Dr. Rosenfeld says.

In the southwest, cool-roof pastel colors or bright white tile can cost a bit more than the standard reddish color – although there are tile suppliers that charge about the same cost for cool colors, roofing industry experts say.

“I went through their calculations and got roughly the same numbers,” says Michael MacCracken, former director of climate-change research under President Bill Clinton. “Some of it is a bit idealized. But what they say is a valid thing to do for any single building ... and seems valuable for an urban area to try to reduce heat-island effects while realizing some contributions for the globe as well.”

Still, not everyone is enthusiastic. Roofing contractors who specialize in solid black asphalt-based roofs and roofing materials have told Akbari they think the idea is for the birds. Even those who like the idea worry it will run into resistance from homeowners who don’t like white.

Right now in California the Old World “vintage look” in clay tile – dark reds or browns – is more popular, not the light greens, blues, and pinks that some cool-roof tile companies offer.

“I personally think all-white rooftops and walls are beautiful,” says Yoshi Suzuki, president of MCA Clay Tile in Corona, Calif. “But not everyone likes white.... Even with a rebate we are finding the cool-roof colors can be a tough sell.”

But that reticence will change in July 2009 when California begins requiring sloping rooftops (mostly residential) to be light-colored cool-roof colors, if not white, Rosenfeld says.

One reason: The mandate will be an economic boon to homeowners, he says. Past studies have shown that white roofs’ net energy savings (cooling-energy savings minus heating-energy penalties) are around 20 percent. Such savings would save the United States more than $1 billion a year on air conditioning, the study says. Getting the white-roof ethos rolling could be a challenge. But two paths could spread white roofs worldwide, Rosenfeld says. In the US, growing economic incentives for cool-roof standards to lessen homeowner cooling costs will promote the spread of California building standards. Outside the US, he and Akbari say they will push to develop a program at the UN or the Clinton Foundation.

Are the benefits ‘overstated’?

While geoengineers like Alvia Gaskill say the research was worthwhile to focus attention on the issue, the study “greatly overstates the benefits,” he wrote in e-mailed response to the study.

Mr. Gaskill, president of Environmental Reference Materials, a consulting firm in Research Triangle Park, N.C., argues that something much larger and more direct is needed. For example, aircraft could spray sulfur-based compounds into the high atmosphere to reflect sunlight back into space. The effect would be similar to what clouds from volcanic eruptions have done over history. (He also had proposed the idea of plastic sheeting for the Sahara.)

“I’m in favor of doing these types of calculations and proposals,” Gaskill says. “But I’m not sure you can really apply a Los Angeles type model to Lagos, Nigeria, or places in China.”

But Rosenfeld says many obstacles will dissolve in the face of the profit motive.

India and China are already eligible under Kyoto’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) to be paid for projects that qualify as carbon offsets. Prices for CDM offsets for CO2 now run $25 per ton, Rosenfeld says. Putting cool-roof standards into building codes could mean CDM payments of $250 for every 1,000 square feet of white roof area. “That’s a pretty good incentive,” Rosenfeld notes.