Video-gaming strives for respect. Is it a sport?

Loading...

| Los Angeles

Attention will be riveted on the Olympic torch Friday during the opening ceremony of the 29th Olympiad, but in cyberspace, another torch relay is under way to promote visibility of a “sport” not yet ready for prime time in Beijing. It is the digital torch of the World Cyber Games, being passed from country to country, ultimately to land in Cologne, Germany, on Aug. 11.

World Cyber Games? That’s right: pro video-game play.

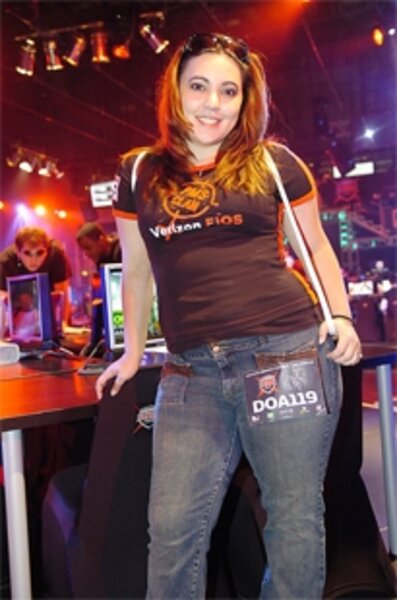

Before anyone snickers, remember that sports channel ESPN routinely showcases poker tournaments, which arguably involve even less athleticism than video-gaming. Indeed, competitive video-game leagues have contracts with ESPN, MTV, and DirecTV, draw as many as 80,000 paying fans to arena events, and boast dozens of formal teams that pay salaries of up to $90,000 a year, putting video-gaming on the cusp of mainstream competition.

“Video games are only getting bigger and more pervasive,” says Michael Kane, author of the book “Game Boys: Professional Videogaming’s Rise from the Basement to the Big Time.” “So the question is, what about the kids who are the best at it? Will they be rewarded for their ability? That’s the attempt being made now, and they are moving forward with baby steps.”

As recently as two years ago, he says, some 15 young aspirants were making roughly $20,000 each. Today, as many as 90 full-time professionals make as much as $90,000 a year, he says.

The World Cyber Games (WCG), which get under way in Cologne Nov. 5-9, is one of three international leagues devoted to promoting, showcasing, and ultimately profiting from video-game competition. (The Championship Gaming Series and Major League Gaming are the others.)

Every sport has its Michael Jordan or Tiger Woods. But a young sport may need a superstar just to let the world know it exists. Enter Johnathan Wendel, aka “Fatal1ty,” the top professional video-game player, or “cyberathlete,” in the West and the first to be considered a full-time pro at the sport.

He began his career in 1999, at 18, when he placed third in a tournament and took home $4,000. His parents had hoped the high school tennis player (a state-ranked player) would go on to college, but once he began to earn real money, Mr. Wendel says, “it was all about the freedom of leaving home and doing what I really wanted to do – and being able to make a living doing it.”

First-person, shooter-style games are his forte, he says, adding that “Painkiller” is his favorite. His career has taken him to every continent but Antarctica and enabled him to move into the heady ranks of athletes who make more money from endorsements and sponsorships than they do from salaries or winnings. For Fatal1ty, income from endorsements, licensing fees, and winnings have surpassed half a million dollars this year alone. “Not bad for a sport most of the world doesn’t even know exists,” he laughs.

Last August, Wendel became the first recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the nascent eSports, a group devoted to promoting cybercompetition. While he still competes, he sees his most important job as promoting the sport itself. “I want to get the word out to people who don’t understand what professional gaming is all about,” says Wendel.

Aware that most people over age 30 would roll their eyes at the idea of calling video-gaming a professional sport, Wendel takes his physical training seriously. He runs four to six miles a day, goes to the gym three or four days a week, and plays games two to four hours a day to stay in shape.

“It requires the same sort of stamina, reflexes, mental strategies, and decisionmaking that any sport would,” he says.

The rise of professional players is proof that the $32 billion a year video-game industry has come of age as a sport as well as a business, says Amy Lee, director of Career Services at Art Institute of Las Vegas Game Art and Design. “Fatal1ty is just leading the way,” she says, adding that she now routinely counsels college grads for lucrative careers in the industry, where skilled players can find work as testers and designers as well as competitors.

“Fatal1ty certainly has had the media attention that was required to galvanize the market and start to focus on pro gaming,” says Ted Owen, chairman and founder of the Global Gaming League.

Unmarried and peripatetic – “I’m sleeping in my business partner’s guesthouse right now,” he says – Wendel says the life of a professional video-game player is as much work as it is play.

“It’s the same way with the big rock-’n’-roll stars,” he says. “You think it’s all glitz and glamour, but it’s a lot of time on the road, away from your family, sleeping in strange places. It’s fun for now, but it’s also a lot of work.” But, he adds with a sly smile, “nobody can say video games are a waste of time anymore. I’m living proof of that.”