How a computer program became classical music's hot, new composer

Earlier this year, 6-year-old musical prodigy Emily Howell released an 11-track debut album, resembling the work of history's most renowned classical composers. But instead of receiving the praise given to Beethoven, Mozart, or Bach, the California native has become a lightning rod for controversy within the musical community.

Why? Because Emily is not human.

Emily is a computer program, and "her" ability to write original compositions has called into question whether art is as uniquely human as many like to believe.

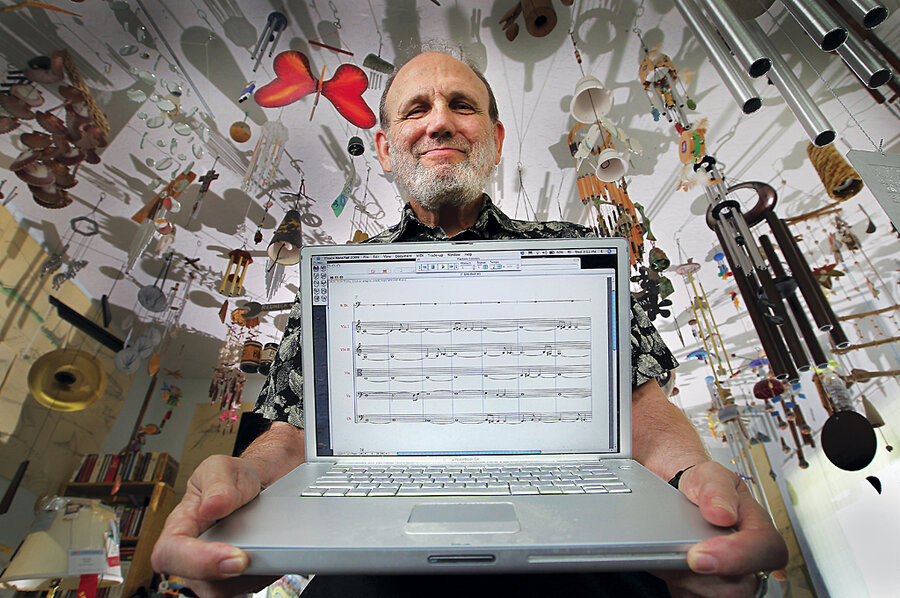

"Can computers be creative? In the sense that they are creating something that wasn't there before, yes," says David Cope, Emily's programmer and professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "But so can birds and insects and volcanoes. We have reserved this notion of creativity for humans for a long time, and we are enamored of it."

As he sees it, creativity has never been a human-defining trait. This feeling of his stretches back three decades, to when Mr. Cope first dabbled in teaching music to computers. After hitting a dead end while trying to write new music on his own, Cope created a program called EMI, which he pronounces as "Emmy."

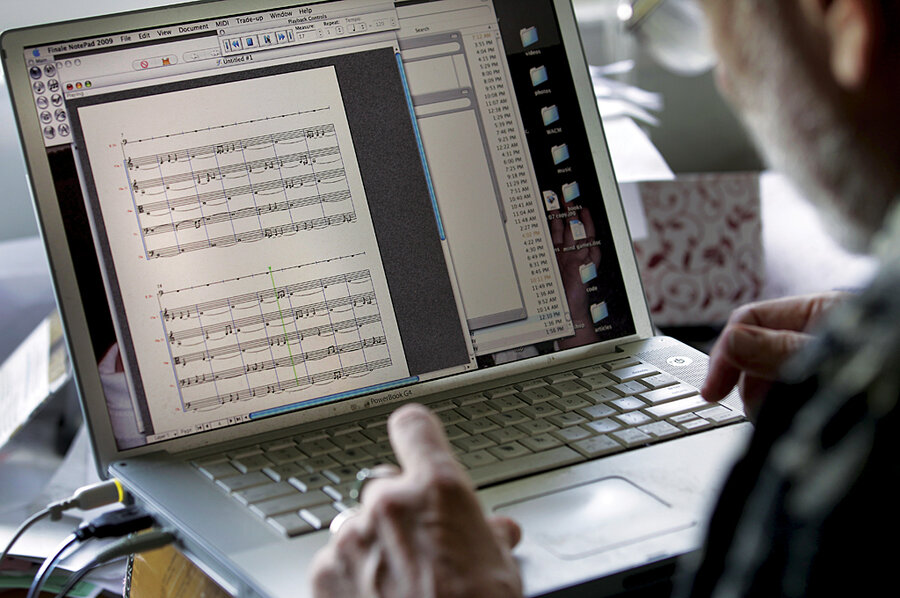

EMI (Experiments in Musical Intelligence) would analyze the work of human composers, pick up on their musical styles, and generate new work seemingly written by the original musician. EMI created "zillions" of compositions before being scrapped for Cope's latest project, he says.

Created in 2003, Emily has only written around 20 songs. It synthesizes its own compositions according to the rules of music that Cope has taught it. And Emily is only fed music that EMI had composed, which gives the new work its own contemporary-classical style.

Human musicians perform most of Emily's compositions, though one song on the album credits three Disklaviers, pianos played by machines.

Cope says he decided to give the software a human name – which has led some to believe it's a real person – because he did not want people to think of Emily as a novelty. Nor did he want her true identity to prejudice listeners either toward or against the music. Some who praised Emily's work before they knew who "she" was, later played down their reactions after learning the music was written by a computer, Cope says.

Some composers seem threatened by a computer program that can produce original compositions, he says. But Cope points out that Emily is still, on some level, a human creation.

"If people were able to [program a computer to be creative], would it make us more or less creative?" Cope asks. "I'd say more."

He believes that Emily, which is "nowhere near artificial intelligence," and other artistically able machines signal a chance for collaboration with human artists, not a digital replacement for them. "Computers are there [for us] to extend ourselves through them," he says. "It seems so utterly natural to me. It's not like I taught a rock to compose music."

Los Angeles Times classical-music critic Mark Swed says although he has received copies of Emily's works, he has not listened to them yet, in part because the composer is a computer.

Fred Childs, host of the popular public radio show "Performance Today," says he was impressed with Emily's songs.

"I enjoyed them," Mr. Childs says. "I thought they were really accomplished imitations of other composers' styles." However, "it felt a little mechanical in a way. But then again, I knew I was listening to a computer," he added. "If I hadn't known that, I might've thought it's the work of some not-so-great composer who is trying some interesting things, but not quite getting it."

The fact that a computer can create music that's indistinguishable from what a human can compose "scares" Childs a bit, but he says he has no problem with the idea of computers writing music.

"The proof is not in who composes it or who is responsible for writing the notes. The proof is in the emotional reaction the music triggers," he says. Emily "wasn't quite there" in terms of sparking his emotions.

Childs's sentiment touches on one of the core problems with computers experimenting with music. In 2008, a study from the University of Sussex in England found that, even when a person does not know the source of a performance, the human brain has a stronger emotional response to music played by humans than work performed by a computer.

Similarly, some question Cope's assertion that Emily is truly an artistic machine. "I think there's a creative aspect to music that is still well beyond what a computer can do," says Aniruddh Patel, a senior fellow at The Neurosciences Institute in San Diego.

Others have argued that Cope's invention and his claims that its work is truly creative is disrespectful to artists who put passion, emotion, and feelings into their work based on years of human experience – something a computer can't share.

But Cope says he welcomes such criticism. "I want people to have different ideas than me," he says. "My wife will tell you one of the strangest things about me is I enjoy the controversy.... As a teacher that's how you learn things."

Emily's album, "From Darkness, Light," is available in some music shops and through Apple's online iTunes Store. Cope says the young composer will follow up with a new album annually for the next five or six years.