The challenge of fair-trade chocolate

Loading...

YAMASÁ, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC - For decades, the Dominican Republic exported tons of low-grade cacao, the chocolate bean, primarily to the United States for use in products like chocolate bars and powdered cocoa. Most of the profits from these sales flowed to a few Dominican companies, which dominated the industry. Relatively little trickled down to the island nation’s tens of thousands of small-scale cacao farmers.

So in the early 1980s, when a German technical-assistance group proposed improving the quality of Dominican cacao, government economist Isidoro de la Rosa embraced the plan – with a twist. Instead of implementing a centralized fermentation system to improve the chocolate, as the Germans proposed, he urged a decentralized approach. Associations of Dominican farmers would learn the fermentation process. An umbrella organization would sell directly to world buyers on their behalf.

From that seed of an idea has sprung a powerhouse. The National Confederation of Dominican Cacao Producers (CONACADO), formed in 1988, has 182 associations organized into eight regional blocks. With a 60 percent share, it’s the biggest single exporter in the small but rapidly growing world market for organic cacao. And it has become a big player in another growing market: fair-trade certified chocolate.

Now, some wonder whether success is going to spoil CONACADO’s recipe. As fair trade continues to grow, will its transition into the mainstream enhance its prospects – or prove it to be, ironically, unsustainable?

“What we’re seeing is rapid growth in demand, so there’s ample room for increased production,” says Laura Raynolds, codirector of Colorado State University’s Center for Fair and Alternative Trade Studies in Fort Collins. But “as this market expands, does it begin to undermine the initial values that the movement seeks to espouse?” Ms. Raynolds doesn’t think so, but others aren’t so sure.

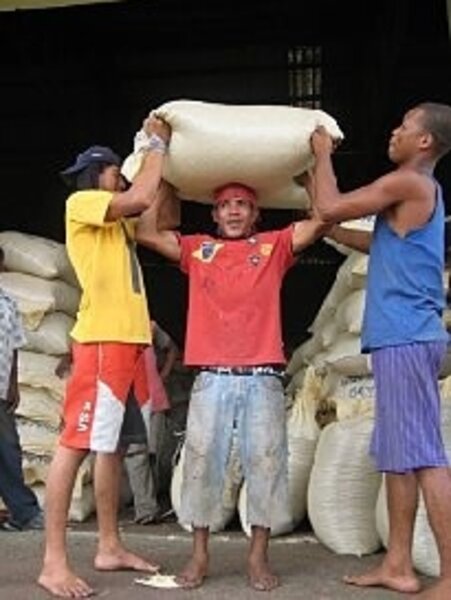

On an overcast March day in Yamasá, in a hilly region north of Santo Domingo, the sour smell of the white-fleshed cacao fruit pervades the air. Smoke rises from burning coconut husks, used to roast the cacao seeds. Young men, balancing 150-pound bags of cacao on their heads, make their way toward a warehouse of CONACADO’S Block 2. The piles of labeled sacks inside will end up in Europe, the US, and Japan.

From the beginning, Mr. de la Rosa knew that the farmers’ only chance of entering the cacao trade directly lay in circumventing the Dominican middlemen who controlled access to the market. That meant moving into a different market entirely: high-quality chocolate in Europe.

Then, as world chocolate prices plummeted in the 1990s, CONACADO moved into the emerging organic market, where prices were substantially higher. By historical artifact, Dominican cacao farmers were perfectly positioned to enter the new niche market. Relatively poor, they had never adopted the pesticide- and fertilizer-intensive methods of modern agriculture. To go organic, they didn’t have to radically alter their farming practices, says Raynolds. Initially, they profited from being the first in the organic market, but as competitors emerged, CONACADO needed a new edge.

Already organized as a cooperative, CONACADO found its new advantage in fair trade – by definition off limits to large commercial producers. The idea behind fair trade: Buyers in the developed world agree to pay at least a guaranteed minimum price to small producers of coffee, bananas, and other exports from the developing world. The built-in floor to prices theoretically protects farmers from being wiped out by major market fluctuations.

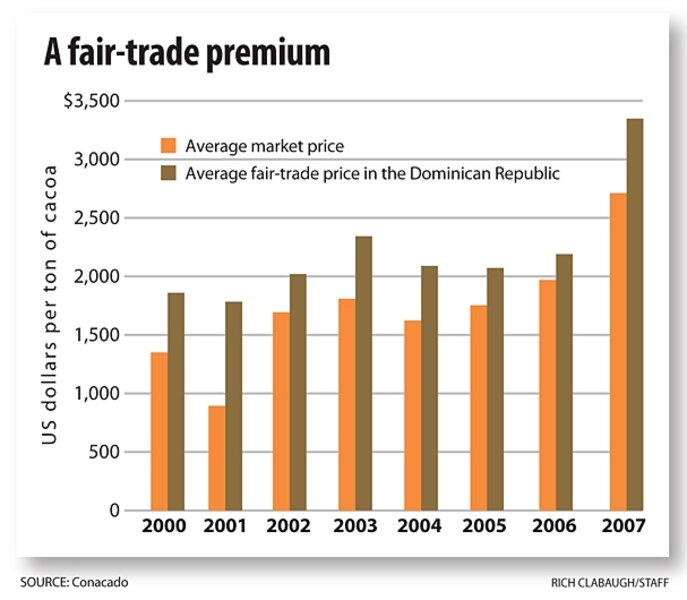

Depending on the market, the fair-trade guarantees can translate to substantially higher-than-market selling prices. In 2001, for example, a ton of fair-trade cacao, which has a floor price of $1,600, fetched nearly double the market average of $894.

“That’s an effect that you recycle,” says Abel Fernandez, CONACADO’s export manager. “You make investments, improve your quality. You have a greater volume of higher-quality stuff. And you make more investments.”

Fair trade also includes a social premium: $150 extra per ton earmarked for investment in social infrastructure. In the past eight years, CONACADO has put $500,000 annually toward schools, medical clinics, wells, and plumbing.

“You can imagine what a difference that makes,” says Mr. Fernandez.

Fair-trade labels first began appearing in the late 1980s, when plummeting commodities prices were wreaking havoc in developing economies. Although still a small portion of the overall market, the fair-trade sector has grown rapidly. Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International (FLO) certified more than $3.62 billion worth of products in 2007, a 47 percent increase over 2006. But continued success even in the fair-trade marketplace isn’t guaranteed, says Raynolds. The mainstreaming of a niche market can change it dramatically. In the organic banana market, for example – the Dominican Republic is also the world’s largest single producer of organic bananas – the mainstream acceptance of organic bananas has, paradoxically, made life more difficult for small producers. Mainstream consumers are less tolerant of blemishes, and they want uniform size, qualities not easily achieved by many small farmers.

Critics charge that, besides pushing onto farmers an agenda whose effectiveness is questionable – namely, cooperatives – fair trade’s price guarantees distort the market. Like subsidies for corn growers in the US, guaranteed prices will cause a glut of producers – more than that warranted by demand, they say. Increased supply into a market with fixed demand could bring down prices everywhere, ultimately hurting many more poor farmers than it helps, says Peter Griffiths, a freelance marketing economist in Edinburgh, Scotland, with experience in the developing world.

“They’re making their money by saying everyone else is crooked,” he says. “And by doing this, they’re pushing down the demand for perfectly legitimately traded coffee.”

Other free-market advocates are less critical. “If an individual consumer wants to pay above-market price to get a warm fuzzy feeling, I have no problem at all,” says Sallie James, a trade-policy analyst at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C. “As long as it’s not coercive and as long as taxpayers are not forced to pay above-market prices, I’ve got nothing against it.”

Fair-trade proponents say that the practice doesn’t artificially bloat prices. Rather, it accounts for costs that the free market fails to include, such as those required to farm sustainably and maintain a viable community. Since there are precedents to this approach in the developed world, like the minimum wage, they argue, why not apply the same principles to internationally traded goods?

“We have to see smallholder producers as more than just economic actors responding to price signals,” says Daniel Jaffee, a sociologist at Washington State University in Vancouver. “To force [them] to basically compete on the unprotected world market is a recipe for social and ecological disaster.”

A growing number of impact studies indicate that, whatever its long-term prognosis, fair trade has improved the lot of some small producers. One study found that a floor on prices lessened Nicaraguan coffee farmers’ vulnerability to market fluctuations. Another in Bolivia concluded that fair trade not only reduced poverty, but the potential for conflict as well. It also increased what buyers were willing to pay even in non-fair-trade markets.

“Yes, it makes a difference,” says Professor Jaffee, who studied fair-trade and conventional coffee farmers in Mexico, but the costs of fair-trade certification and administration were prohibitive for some, he says.

Like other initially small movements that go mainstream, some wonder if fair trade might fall victim to its own success. Jaffee has noted that large firms’ entry into the fair-trade market has partially undermined the movement’s founding principles.

“The entry of large commercial firms has worked against raising minimum prices,” he says.

“What was a clear living wage in the late ’80s when the movement was founded [is] less so now.”

But Raynolds points out that although large firms have entered the market, the smaller players, like the nonprofit Equal Exchange, CONACADO’s US buyer, never got pushed out.