Will Obama's healthcare reform plan cut costs?

Loading...

For many Americans, the question of whether to support President Obama on healthcare reform boils down to something very basic: Will the plan help control medical costs or send those costs spiraling still higher?

The president has made bold claims.

"My proposal would bring down the cost of healthcare for millions – families, businesses, and the federal government," Mr. Obama said on March 4, urging Congress to approve the stalled reform package.

American voters remain skeptical.

In a February ABC News/Washington Post poll, 59 percent of Americans called Obama's plan "too expensive." Other polls in recent months have found a majority predicting that the changes will raise their own medical costs, boost healthcare spending nationwide, and push up the federal budget deficit.

Such doubts are a big reason the president has had such a hard time moving his plan – many elements of which the public supports – toward the legislative end zone. What's the reality about Obama's plan and costs?

Although it's a complex and hotly debated issue, many of the plan's backers and foes agree on some important points:

•At first, America's overall healthcare spending is likely to head higher than it otherwise would. The reason is that an estimated 30 million or more Americans will be newly insured.

The core of Obama's initiative is a mandate for individuals to buy insurance, coupled with subsidies to help pay for it and penalties for people who don't buy it.

•Obama intends to cover those new costs, without adding to federal deficits, mainly by squeezing efficiencies out of Medicare for seniors.

The reality is, these planned savings are uncertain. If seniors observed a decline in their quality of care, for example, a future Congress might be tempted to open the spending spigot wider.

•Government's role in the healthcare system would go up. That could be good or bad for cost control, depending on your view. Proponents say more regulation would provide needed leverage, while opponents would prefer to rely more on enhancing marketplace competition.

•Even if the reforms work well, they're a partial fix – a start down the road to cost containment. With or without reforms, forecasters see the nation's healthcare spending rising sharply over the next decade. The question is not so much whether healthcare costs will rise, but how much.

"The test [for Obama's plan] will be whether the rate of growth of healthcare spending relative to total income is higher or lower than it has been in the past," says Henry Aaron, a health policy expert at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank that tends to be centrist or left-leaning.

In recent decades, he says, the rate of healthcare spending has outpaced income growth by about 2.5 percentage points a year. That pattern, compounded over time, is proving very costly.

Many healthcare experts say it's not surprising, given longer life spans and the evolution of new medical treatments, that healthcare accounts for a rising share of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP).

But rising costs are still a vital concern, to the degree that fees are soaring not because of the intrinsic value of care but because the system lacks incentives to curb costs. The risk is that rising costs will erode family finances, slow economic growth, and make the US Treasury essentially go broke.

Here's a rundown of key elements of the Obama plan, or the December Senate plan on which it's heavily based, and the financial impact. Note that any cost estimates come with what forecasters acknowledge is a very large degree of uncertainty.

Insurance 'exchange'

Individuals who don't have employer-based coverage or Medicaid would shop for insurance through an exchange, where providers complied with basic coverage standards.

"The exchanges could grow into a very powerful mechanism for cost control," Mr. Aaron says.

It's an idea with some appeal for both conservatives (through its potential for consumer choice and competition among insurers) and liberals (through regulations, such as preventing insurers from dropping coverage).

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that individuals would see premiums for a given amount of coverage go down by as much as 10 percent due to the reforms. But the CBO added that many people would end up paying more for insurance anyway because they'll buy a greater amount of insurance coverage.

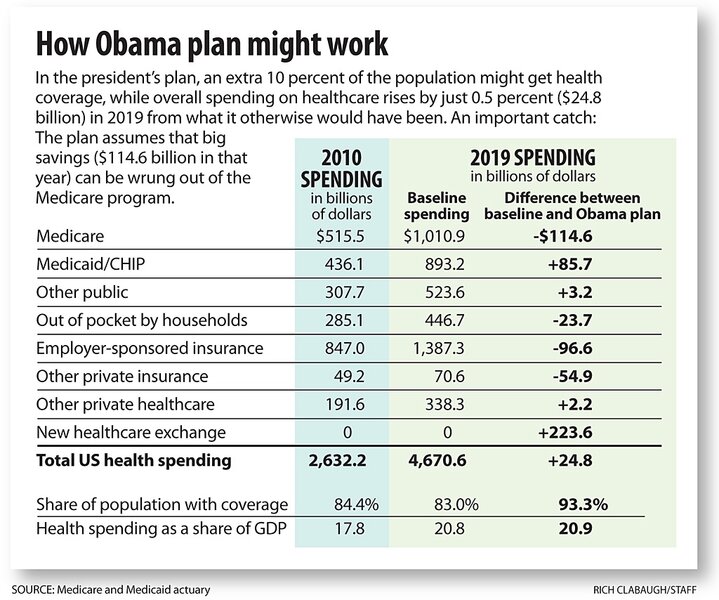

Overall, the reform elements designed to expand insurance coverage would cost the government an extra $181 billion in 2019, to use one year when the reforms are fully in effect, according to an estimate by Richard Foster, chief actuary for the government's Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The report estimates that 22 million Americans would be uninsured in that year, 34 million fewer than without the reforms.

A key idea behind the mandate on individuals is to see that, as insurers face a new requirement to offer coverage without regard to consumers' preexisting health conditions, people don't wait until they're sick to buy coverage. But Obama would offer a "hardship" exemption if insurance would cost more than 8 percent of one's annual income.

Employer-based coverage

The CBO estimated that reforms wouldn't push private-sector insurance premiums up or down much for people in large- or small-group plans.

One big uncertainty is how many employers would drop coverage (and pay a $2,000-per-worker fine if they have 50 or more employees).

Some government estimates of the reform's impact envision relatively few employers doing this. The more that do, the higher the government's health tab will go, because more people will qualify for subsidies as they shop for individual insurance.

Meanwhile, a tax on the highest-end private health plans is part of Obama's plan for keeping the reforms "deficit-neutral" for the federal budget.

Medicare

Obama seeks to trim some $540 billion from the growth of Medicare spending over the first decade of his reforms. The main way: slowing the growth of payment rates to hospitals.

Health policy experts say this may not be hard at the beginning, but will get more difficult over time. Some doctors could end up backing out of the Medicare program, for example.

Joseph Antos, a healthcare expert at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, also worries that a key reform provision – setting up an independent board to curb Medicare costs – is too weak to be effective.

"It's in the nature of politicians to want to give people things and not take them away," he says.

Medicaid

The plan would expand Medicaid coverage to people with incomes at 133 percent of the official poverty level. About 19 million more Americans would be insured because of this in 2019, estimates Mr. Foster, the Medicare/Medicaid actuary.

As a result, spending on Medicaid would be an estimated $86 billion higher in that year – a figure that's part of the total $181 billion (cited above) in government spending on expanded coverage.

Long-term care

The reforms include a so-called CLASS Act, which would set up a voluntary insurance program to cover assisted-living costs. During the next decade, the program would be a modest revenue-raiser for the government, because of a five-year period before people can start collecting benefits.

But Foster, among others, warns of "a very serious risk that the program would become unsustainable," because the several million people who sign up would be those most likely to draw benefits.