Crowdsourcing science: how gamers are changing scientific discovery

Loading...

For 15 years, scientists and their computers had tried to solve a biological puzzle seen as a key hurdle in the fight against AIDS.

On Sept. 18, the journal Nature Structural & Molecular Biology announced that two teams of computer gamers had solved it in three weeks.

Using a game called FoldIt, the teams uncovered the structure of a class of proteins scientists say is vital to the growth and reproduction of the virus linked to AIDS. The discovery could help scientists neutralize the protein.

FoldIt represents a unique approach toward engaging citizen scientists, and it is the latest innovation in a decade-long trend – researchers enlisting everyday people and their personal computers to take part in humanity's scientific enterprise.

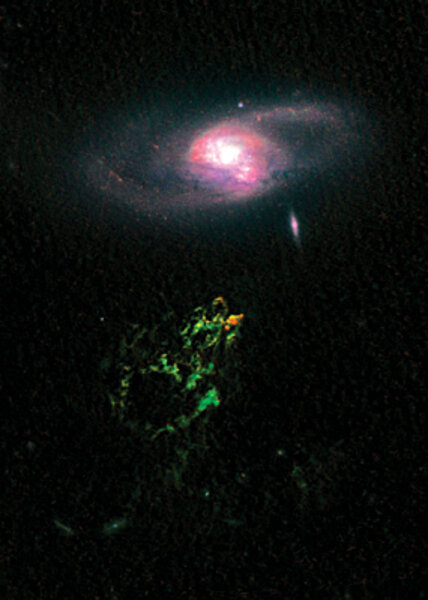

Some scientists, like FoldIt's creators, seek to tap the competitive, problem-solving skills of gamers. Others are asking outsiders to make their computers part of data-crunching networks. And some amateurs are helping to classify everything from distant galaxies to features on the moon.

Such efforts are likely to play an increasingly important role in science, researchers say. Many research questions are getting harder to answer and require more data than ever before. And the ranks of scientists and their graduate students aren't growing fast enough.

Whatever the approach, Main Street recruits and their computers are playing a useful role in accelerating the pace of scientific discovery.

With FoldIt, the idea was to involve humans in the kind of problem solving that often befuddles computers.

In the world of proteins, shape is everything, but computers have a tough time analyzing it. Humans, however, excel at 3-D pattern recognition and can wield the game's online tools to shape the protein. Meanwhile, the game acts as a referee should team members run afoul of the basic physics that govern bonding between the molecules involved. The less energy needed to retain the protein's shape, the higher a team's score.

The approach aims "to engage people for an extended period of time such that they actually go from novices to experts," says Zoran Popovic, head of the Center for Game Science at the University of Washington in Seattle and FoldIt architect.

A different approach – building a network of public computers – has risen steadily since May 1999, when SETI@home began. SETI@home taps nearly 3 million computers owned by 2.1 million users to sift through data from the Arecibo Radio Telescope in Puerto Rico for potential signals from extraterrestrials.

Currently, some 37 other projects have turned to this distributed-computing approach for help.

But in some cases, raw computing power is not enough. Scientists need human eyeballs to help analyze reams of images coming in from various scientific fields. To meet this need, Chris Lintott, an astrophysicist at Oxford University, has set up Zooniverse – a budding Grand Central Terminal for researchers who need public assistance in an eyes-on way.

The scientists aren't necessarily seeking people with advanced degrees. Instead, many projects prize a keen eye, a good ear, or puzzle-solving skills.

For example, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which is still in the design phase, will eventually flood computer servers with 30 trillion bytes of data each night. The Hubble Space Telescope, by contrast, spent its first 20 years amassing 45 trillion bytes of data. As these data arrive, scientists will be looking for signs of change from previous views of the same patch of sky. Perhaps a supernova has erupted. Or a new or long-missing comet or asteroid has appeared.

A computer might sort through the data and channel some to computers and some to humans for analysis. If an image is tagged for human eyes, the system might look to see who is online and ship the image to the person with the best track record for identifying similar images.

"Or maybe you're walking down the street and your phone buzzes" with a message that says, "We've got one we really need your help on," Mr. Lintott says.

The most recent project to enlist citizen scientists for analysis is Planet Hunters, which began last December.

The project enlists volunteers to take close looks at the light curves from stars observed by NASA's Kepler mission as it hunts for Earth-size planets orbiting sunlike stars. Those light curves – which trace changes in a star's brightness with time – not only harbor evidence of planets, but also reveal a wealth of precise information about the stars themselves.

Kepler scientists get first crack at the data, but that leaves the door open to identifying planet candidates the Kepler team may have missed. Sure enough, the Planet Hunters team has bagged two new planet candidates after combing through data the Kepler mission's formal science team had already mined.

Since the inception of Planet Hunters, volunteers have classified light curves that would take one person 60 years to process, says Yale University astronomer Debra Fischer, one of the scientists running the Planet Hunters program.