Mystery of Comet Lovejoy: How'd it survive close encounter with the sun?

Comet Lovejoy lives to orbit another 314 years.

Icarus should have been so lucky.

The comet, discovered by Australian amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy Nov. 27, defied expectations that it would be destroyed during its closest approach to the sun late Thursday.

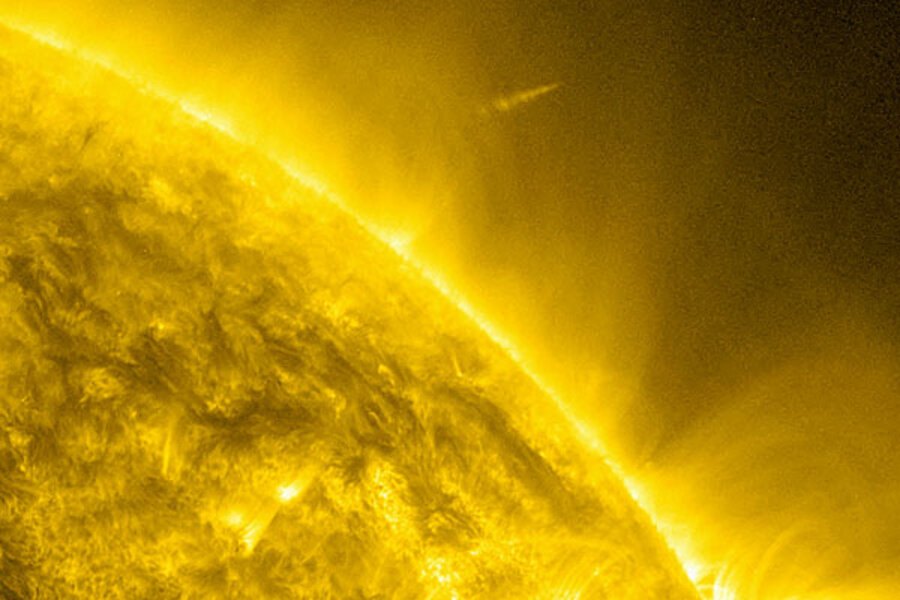

Instead, NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory satellite saw the comet emerge from behind the sun between 7 and 8 p.m. Eastern time Thursday, surviving a passage through the sun's corona and its searing 2-million-degree temperatures.

Prior to the comet's swing-by, which took it to within about 87,000 miles of the sun's surface, scientists expected the comet, formally designated C/2011 W3, to vaporize.

In anticipation, five sun-watching spacecraft from the US, Europe, and Japan trained their instruments on the object to take advantage of the rare opportunity to chronicle a comet's final encounter with the sun.

"I suppose the first thing to say is this: I was wrong. Wrong, wrong, wrong," wrote astronomer Karl Battams, with the US Naval Observatory, who has been blogging about what he calculated as Comet Lovejoy's impending demise. "And I have never been so happy to be wrong!"

Why? Because, he says, that's when scientists really learn something.

One question relates to the comet's size.

"This is one case where size counts," says Dean Pesnell, project scientist for the Solar Dynamics Observatory at the Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "The bigger you are, the more likely you can make it through the closest approach to the sun," or perihelion.

Because the comet was very bright during its approach, "we knew it was a bigger one to start with," Dr. Pesnell says. But it was tough to put a number to the mass.

Because the comet survived, researchers now estimate its mass to be at least 1 billion kilograms, or 1.1 million tons.

Dr. Battams says he initially estimated the size of the nucleus at no more than about 200 meters across, roughly two football fields set end to end. Now, he says, it's more likely that the nucleus measures significantly larger.

In addition, the Solar Dynamics Observatory has been gathering spectra from the comet to understand its composition.

With all the spacecraft available to observe the comet's close encounter with the sun, scientists have been able to track far more of its torrid travels. The Solar Dynamics Observatory captured the comet as it flitted behind the sun, then re-emerged. One of NASA's two Stereo spacecraft was in position to capture the comet as it crossed the far side of the sun. It too has been gathering data on the comet's composition, Pesnell says.

Comet C/2011 W3 belongs to a class of comets known as Kreutz sungrazers. They were named for German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz who, in 1888, published calculations showing that three sungrazing comets observed between 1843 and 1882 were probably fragments of one larger comet that had broken up during its solar encounter several orbits earlier.

These three comets were dubbed "great" comets because of they were bright enough to be see even by casual observers without the aid of binoculars or telescopes. And some were visible during the day.

All Kreutz sungrazers are now considered to be fragments of that one original comet.