What the transit of Venus tells us about alien planets

Loading...

A rare opportunity to see the planet Venus cross in front of the face of the sun is coming up next week.

On June 5 to 6, Venus will "transit" the sun for the last time until 2117, joining the ranks of the handful of planetary transits that have occurred since the dawn of modern astronomy.

From our vantage point on Earth, we occasionally have the chance to see two planets — Venus and Mercury — pass in front of the sun, as these are the only two planetary bodies between us and our star.

Transits of Mercury are more common than Venus transits, with an average of 13 occurring each century. Venus transits come in pairs separated by eight years, with more than a century usually elapsing between one pair and the next. [Gallery: Transits of Venus Throughout History]

"The first transit ever observed was of the planet Mercury in 1631 by the French astronomer [Pierre] Gassendi," Fred Espenak, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., wrote on the NASA Eclipse website. "A transit of Venus occurred just one month later, but Gassendi's attempt to observe it failed because the transit was not visible from Europe. In 1639, Jeremiah Horrocks and William Crabtree became the first to witness a transit of Venus."

Planetary transits through history

Historically, planetary transits have offered a rare chance for scientists to learn about the solar system.

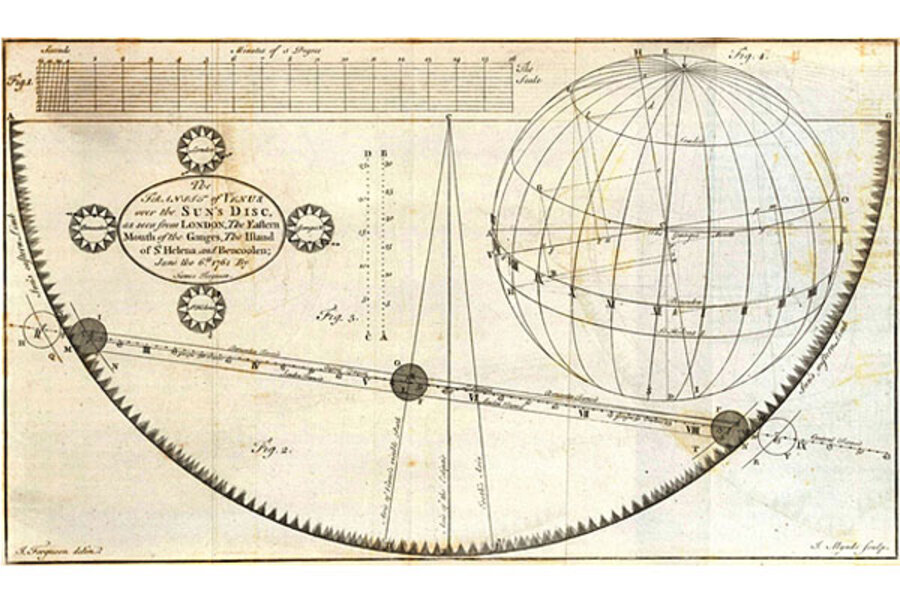

In the 18th century, transits of Venus provided astronomers with the first way to measure the absolute size of the solar system, including the distance from the Earth to the sun, which wasn't known at the time. Astronomer Edmond Halley first came up with the method of comparing measurements made from various locations on Earth to triangulate the distances to Venus and the sun.

This technique was successfully put into practice during expeditions to observe the Venus transits of 1761 and 1769 from around the world.

And even as recently as 2006, the transit of Mercury was used to measure the size of the sun. A group of astronomers from Hawaii, Brazil and California used NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) to time the transits of Mercury across sun in 2003 and 2006, enabling the most precise measurement yet of the diameter of the sun.

"Transits of Mercury occur 12 to 13 times per century, so observations like this allow us to refine our understanding of the sun’s inner structure, and the connections between the sun’s output and Earth’s climate," one of the members of the team, University of Hawaii astronomer Jeff Kuhn, said in a statement.

And the science being planned for the upcoming Venus transit is a step ahead of research done during the 2004 Venus transit, as instrumentation and research goals have advanced, said Matt Penn, lead scientist at the McMath-Pierce Solar Telescope at Kitt Peak observatory in Arizona. [2012 Venus Transit Observer's Guide (Infographic)]

Much of the research during the past Venus transit focused on using spectroscopy — a technique to divide light into its constituent wavelengths — while looking for polarized light will be the thrust of many researchers' aims this time around, he said.

"The opportunity to read what other people did in 2004 and to build on their work is a unique opportunity," Penn told SPACE.com. "We're hoping that one of the experiments will allow us to detect polarization through Venus' atmosphere."

Venus ties to alien planets

The upcoming transit will be used not just to study the architecture of our own solar system, but that of others as well.

"Astronomers in the 18th and 19th centuries observed transits of Mercury and Venus to help measure the distance from Earth to sun," said Frank Hill, director of the National Solar Observatory’s Integrated Synoptic Program. "We have that number nailed down now, but transits are still useful. This one will help us calibrate in several different instruments, and hunt for extrasolar planets with atmospheres."

The transits of alien planets in front of their stars, from the point of view of Earth, are one of the key ways scientists discover such planets' existence. As planets pass in front of their stars, they briefly dim the stars' light, signaling their presence.

And just as with Mercury and Venus, the filtering of stars' light through planets' atmospheres can reveal clues regarding the presence and composition of gaseous atmospheres around these distant worlds.

Since scientists know quite a lot about Venus' atmosphere by now, they can use observations of its transit to calibrate their instruments and set a benchmark for studying the atmospheres of new planets beyond the solar system.

You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.

- Transit of Venus 2012: An Observer's Guide (Gallery)

- The Transit of Venus: Complete Coverage

- Past Venus Transits Revealed Solar System’s Size | Video Part 2

Copyright 2012 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.