What will NASA's Mars rover do when it gets there?

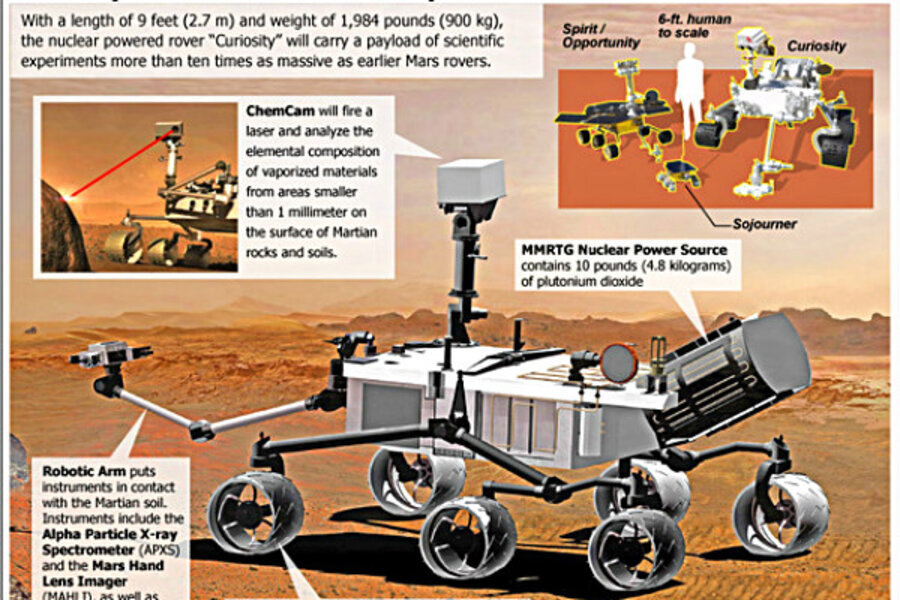

When NASA's next Mars rover, Curiosity, arrives at the Red Planet next month, it will help pave the way for the humans that might one day follow.

In addition to looking for signs of current and past habitability to extraterrestrial life, the rover, due to land Aug. 6, will learn more about whether Mars could be habitable for humans — particularly in terms of its weather. The continuous record of Martian weather and radiation Curiosity plans to collect will help future forecasters tell humans — should we choose to go — how best to protect themselves in the harsh environment, experts say.

That's why NASA's Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate paid to include a radiation detector onboard the car-size Curiosity, the centerpiece of the Mars Science Laboratory mission, which is run by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“When we were designing Curiosity, we were going to use it for our habitability investigations as well,” said Ashwin Vasavada, MSL's deputy project scientist. “But it really is paid for and intended to understand the environment humans will experience on Mars.”

The $2.5 billion rover launched Nov. 26, 2011. It is designed to work for at least two years on Mars.

Curiosity will sample the Martian environment every hour through two main instruments: a meteorology station and a radiation detector. The instruments will run even when the rover is sleeping, during the Martian night, to provide a continual stream of data. [Mars Rover Curiosity's Landing Site: Gale Crater (Infographic)]

The Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD), in fact, began running during Curiosity's eight-month journey to Mars. Radiation from the sun and galactic cosmic rays occur throughout the solar system, meaning that humans would be exposed to elevated radiation from the moment they leave Earth's cradling magnetic field. Understanding how much radiation would bombard the spacecraft is the first step to learning how we can shield humans against it.

When Curiosity begins work on the Red Planet, RAD's telescope detectors will run for 15 minutes every hour, measuring a broad range of high-energy radiation in the atmosphere and on the surface.

It's not fully known just how radiation behaves close to the surface. Although orbiting spacecraft such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter can measure it from above, it's harder for those spacecraft on high to see radiation close to the ground. Of most concern to scientists are rays that can splinter off from radiation hitting the Martian atmosphere.

“The high-energy particles can generate secondary, lower-energy particles when they interact with molecules of gas in the atmosphere,” Vasavada said.

Most particles in cosmic rays are protons, which can generate secondary gamma rays or neutrons, he added. This process also happens on Earth, but higher in the atmosphere and far away from the surface.

According to Vasavada, these energetic particles can ionize molecules inside humans, breaking the molecules apart and damaging cells. Essential complex organic molecules such as DNA could be affected.

“How much damage a particle does is not simply related to how energetic it is,” he said. “Heavier, less energetic particles produced as secondaries may be rarer than protons to an astronaut, but can do just as much total damage.”

Weather forecasting will also be needed for astronauts roaming on Mars. In a first since the Viking vanguard missions of the 1970s, MSL will feature a full meteorology package called the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station. The Spanish–built REMS will run for at least five minutes every hour, night and day.

To capture the speed and direction of the wind, and the air's temperature and humidity, REMS will use electronic sensors on two booms stretching out horizontally from a camera mast mounted on the rover.

Ultraviolet radiation will be measured using a sensor stuck on the rover's deck. Some of the wavelengths it will watch for are the same ones sensed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter flying above, providing a more complete record of what's happening on Mars.

Inside the rover, an air pressure sensor will taste the air outside through a tube with a small opening to the atmosphere. Radiation-sensitive electronics controlling REMS will also stay inside Curiosity to protect them from the elements.

Through coordinating MSL's weather and radiation sensing with what is seen from above, NASA expects a better picture of what Mars looks and feels like, making it easier for humans to get there.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

- Mars Rover Curiosity: Mars Science Lab Coverage

- 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars

- The Best (And Worst) Mars Landings in History

Copyright 2012 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.