Gigantic invisible cocoons of dark matter may suck up rogue stars

Stars ripped from their home galaxies as they collide with other galaxies can get slung into giant invisible cocoons of dark matter, researchers say, which might explain mysterious radiation pervading the sky.

These findings suggest the halos of dark matter surrounding galaxies are not completely dark after all, but contain a small number of stars, investigators added.

In recent decades, satellite telescopes have detected more infrared light emanating from the sky than known galaxies could account for. Scientists had suggested this strange glow might come from sources too dim for observatories to see directly — for instance, the earliest, most distant galaxies. If such primordial galaxies were responsible for this radiation, that might suggest far more of them existed than before thought, potentially radically altering notions of how the cosmos evolved.

Now, using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, astronomers have viewed a sufficiently large enough patch of sky to help shed light on this infrared glow. The researchers found that neither primordial galaxies nor faint dwarf galaxies could explain fluctuations in this excess radiation seen across space.

"We have made new measurements of the glow and found it to be brighter in intensity by several orders of magnitude than the first galaxies," study lead author Asantha Cooray, a cosmologist at the University of California, Irvine, told SPACE.com.

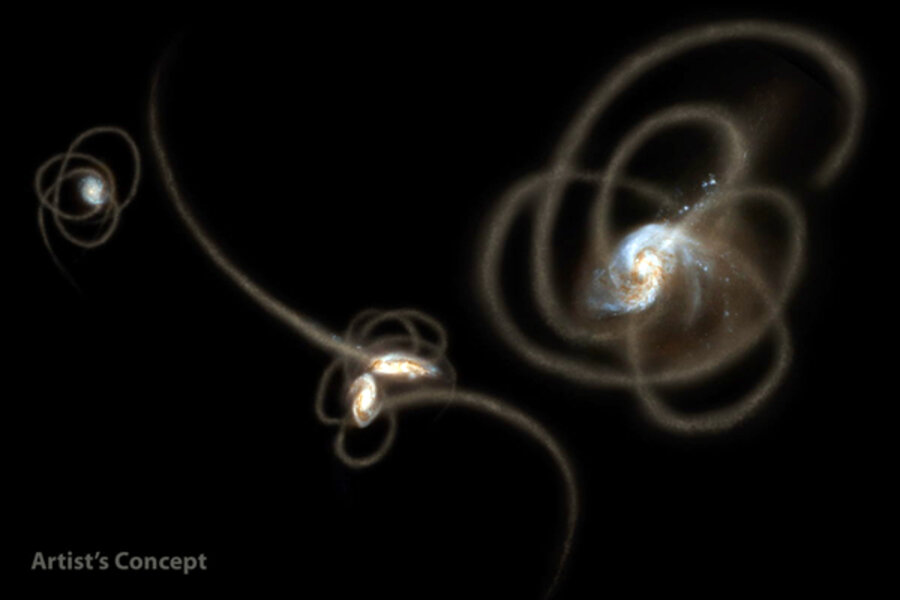

Instead, the researchers suggest wandering stars in the gargantuan spherical halos of dark matter enveloping their home galaxies might be responsible for this mysterious light. Physicists think invisible, as-yet-unidentified dark matter makes up about 85 percent of all matter in the universe.

"These diffuse stripped halo stars explain the missing infrared glow," Cooray said.

These stars were likely torn from the main bodies of their galaxies during epic collisions with other galaxies. They may have also been stripped away from their original homes by other galaxies pulling at them with their gravity, just as the moon's gravity tugs at Earth's oceans to generate tides. [Photos of Great Galaxy Crashes]

"For a typical Milky Way-sized galaxy, the intensity of light coming from these halo stars is about 1 percent of the total light from that galaxy," Cooray said. "That fraction grows rapidly, to as high as 20 percent, in denser galaxy environments like galaxy groups and clusters, as collisions and tidal stripping are more frequent in dense regions of the universe."

Mostly, these stars were only exiled to the most distant outskirts of their home galaxies instead of getting hurled out into intergalactic space, trapped as they were by the gravitational pull of the dark matter halos surrounding their galaxies. Galaxies exist in dark matter halos that are much larger than the galaxies; when galaxies merge together, stars and gas sink to the middle of the resulting combined halo.

"If I sum all of the galaxies out to about a billion years since the Big Bang from today, the stripped diffuse stars contribute about 10 percent of the total infrared light intensity seen by Spitzer — the rest is the light from galaxies," Cooray said. "The previous explanation attributed that 10 percent of unexplained intensity to primordial galaxies and stars, but the most recent estimates by a variety of authors, not just my group, are that the primordial galaxies contribute at most 0.5 percent."

Future research can see whether data from other telescopes and experiments will confirm the research team's model.

"These halo stars, while bright in the infrared, should also emit visible optical light," Cooray said. As such, the Hubble Space Telescope should be able to see these stars as well, he explained.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Oct. 25 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.