How SpaceX Dragon capsule successfully docked at International Space Station

Loading...

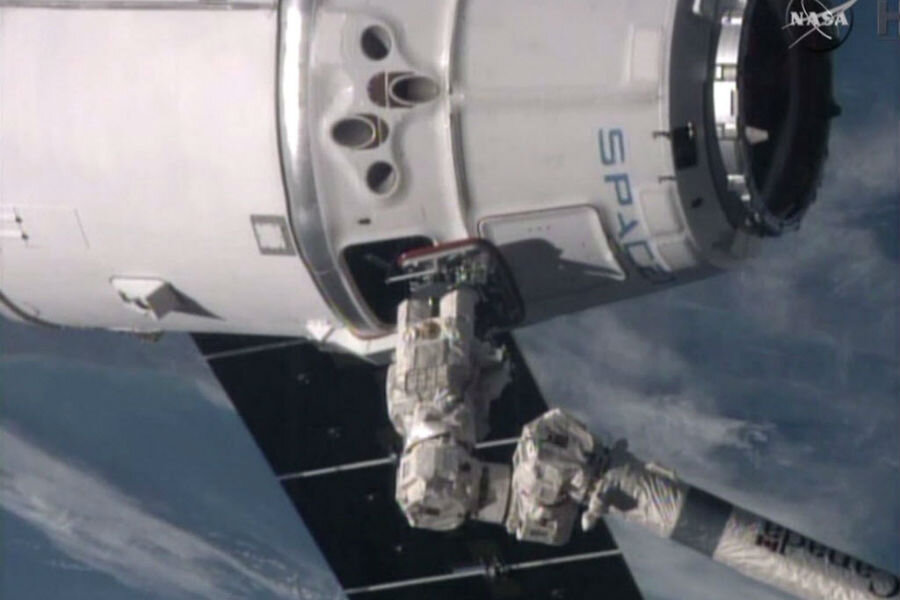

A commercially operated cargo capsule destined for the International Space Station docked with the station Monday following its flawless launch early Saturday.

The rocket and capsule, built and operated by Space Exploration Technologies Corp., lofted some 2-1/2 tons of food, water, science experiments, and other supplies to the orbiting outpost under a $1.6 billion station-resupply contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The mission comes on the heels of an October launch failure involving a resupply mission conducted by Orbital Sciences Corp., the second of two companies the space agency now relies on to ferry cargoes to the station.

At 5:54 a.m. ET Monday, the capsule was lurking some 32 feet from the orbiting outpost, a final holding point before docking. The station's commander and former US Navy test pilot Barry Wilmore and European Space Agency astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti used the station's robotic arm to gently grasp the capsule and pull it into its docking port some 18 minutes ahead of schedule.

During his career as a Navy pilot, Captain Wilmore amassed 663 landings on aircraft carriers. Using a carrier pilot's phrase for a perfect landing, "we'll call that one an OK three-wire; not bad for a Navy guy," quipped astronaut Randolph Bresnik, a former Marine pilot, from the station's mission control center at the Johnson Space Center in Houston when Dragon was firmly in the station's grip.

"We apologize for Santa and his Dragon sleigh for bringing a little bit more on the Eastern Orthodox schedule and calendar," he added – a nod to the Christmas gifts that also came up on Dragon.

The mission's primary goal is resupply, but it also served as an opportunity to test a landing system that SpaceX has designed for the first stage of the Falcon 9 rocket that lofted Dragon. The system is crucial to shifting the first stage from hardware that is used once to hardware that can be recovered and used repeatedly, thus reducing launch costs.

The stage had been redesigned to sport landing legs and four gridded, paddle-like fins to provide the precision steering needed to return the stage upright at a designated landing spot. In this case, the spot was the flat deck of a barge-like craft some 300 feet long and 170 feet wide.

Ten minutes after launch, the first stage reached the vessel, dubbed the autonomous spaceport drone ship. But the stage came down too hard, and the company lost the booster.

"Grid fins worked extremely well from hypersonic velocity to subsonic, but ran out of hydraulic fluid right before landing," tweeted Elon Musk, SpaceX's founder, chief operating officer, and chief technology officer.

The system's hydraulic fluid doesn't flow repeatedly through the system in a closed loop, he noted. Instead, the fluid flows through once. This approach saves weight, but it also means one has to carry enough fluid to do the job.

The fins "work for 4 mins.," he tweeted. "We were ~10 percent off."

The next booster will have 50 percent more hydraulic fluid aboard.

While the company lost the booster, it became the first launch provider to guide a spent booster back to Earth with high precision. Previous experiments had soft-landed boosters in the open ocean with a landing accuracy of about six miles. Given the span between landing legs and the size of the landing deck, setting a booster down on the drone ship requires an accuracy of 32 feet.

"Am super proud of my crew for making huge strides towards reusability on this mission. You guys rock!" Mr. Musk tweeted.