Signs of salt water on Mars: Could it boost possibility of life?

Loading...

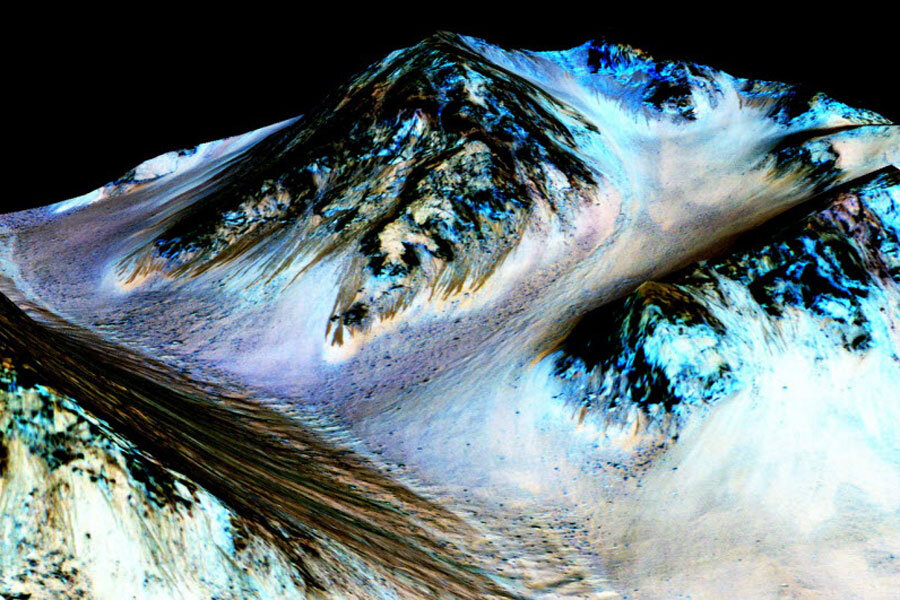

Mars appears to weep, sending salty water down the slopes of canyon and crater walls to form dark streaks that appear and disappear with the seasons.

The analysis that paints this picture represents the strongest evidence yet that water is responsible for these streaks. It is heightening anticipation that useful amounts of water are accessible in many places on the red planet.

Water is a potential resource for humans exploring Mars, as a raw material for rocket fuel as well as for slaking astronauts' thirst. It also is key to making a place livable for simple forms of life. Thus, the dark streaks may be potential destinations for missions that aim to hunt for current life on Mars.

The evidence that water is producing the dark streaks is indirect, but powerful, researchers say. It's based on an abundance of water-bearing salts. The salts are more abundant along the streaks than in the soils in between them, suggesting repeated deposits from current sources, the researchers announcing the results say. And they are capable of soaking up moisture from the atmosphere to become a briny solution.

The results "strongly suggest" that the streaks "are formed by liquid water on present-day Mars," says Mary Beth Wilhelm, a scientist at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and a member of the team reporting the results in Nature Geoscience.

The analysis is most exciting "because it suggests that it would be possible for there to be life today on Mars," says John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for the agency's science mission directorate.

The amounts of water so far appear to be modest. The team estimates that the minimum amount of water needed to explain the streaks at its study sites, a section of Valles Marineris, would fill 40 Olympic-size swimming pools.

"That sounds like a lot if it's all in one place. But that's dispersed over a very wide area," says Alfred McEwen, a researcher at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Tucson. "So what we're dealing with is thin layers of wet soil."

But Mars has a large surface area, so the volume of water planet-wide could be quite large, adds Dr. McEwen, another member of the team reporting the results in Nature Geoscience.

Researchers have been puzzling over these dark streaks since they first were spotted in 2010. They often track gullies carved into slopes. They typically appear on sun-facing slopes during each hemisphere's warm season, only to disappear the rest of the year.

After analyzing a growing number of these streaks, a team led by McEwen concluded last year that the streaks probably come from locally abundant amounts of briny water. The streaks appeared too often to come from melting underground ice, which probably wouldn't be in the equatorial region anyway. And they noted that the streaks' comings and goings may not be determined solely by temperature.

Meanwhile, data from NASA's Curiosity rover at Gale Crater have hinted that soil moisture may be more abundant at higher latitudes on Mars than near its equator.

Earlier this year, scientists published calculations showing that brine could form within the first two inches of the crater's salty soils. The salts essentially drew moisture from the atmosphere.

Curiosity's data suggested that brine formed at night to moisten the soil, then evaporated during the day. At more humid latitudes, the process could trap larger amounts of water, added the researchers involved.

The sources for the streaks the new study analyzes are unclear.

Some people have suggested the sources may be aquifers near the crater or valley walls.

That might work for streaks that originate partway down a slope, notes Dr. Wilhelm. "The weird thing" about the streaks, she says, "is that we usually see the streaks coming from the very top" of a slope. The sources are too near the surface to be aquifers, she suggests.

This has led the team to suggest that the mechanism involves salts sponging moisture from the atmosphere – at least in the regions the team has studied.

The analysis, led by Georgia Tech PhD student Lujendra Ojha, drew on data from an imaging spectrometer on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). The data came from three craters and from Coprates Chasma, which runs along the eastern part of Valles Marineris.

As the team analyzed the spectral signatures of minerals along the streaks, they found nothing that pointed to liquid water. Instead, the spectra resembled a class of salts known as perchlorates. When the team compared the MRO results with the spectra of lab samples, it got the best matches for magnesium chlorate and sodium and magnesium perchlorates.

Sodium and magnesium perchlorates have a powerful effect in stabilizing surface water on Mars, Mr. Ojha explains. These salts can lower water's freezing point by 72 to 126 degrees F., depending on the type. But they also can raise the boiling point. On Mars, the thin atmosphere allows that pure water would boil at about 50 degrees F. Add perchorates, and that temperature rises to 75 degrees.

"The presence of perchlorates vastly increases the stability of water on the surface of Mars," he says.

The researchers acknowledge that different processes could form the brines, depending on location. At the least, the regions they identify merit a closer look during future Mars missions, they hold.