Pluto: A mountainous, flat, frozen, and diverse world

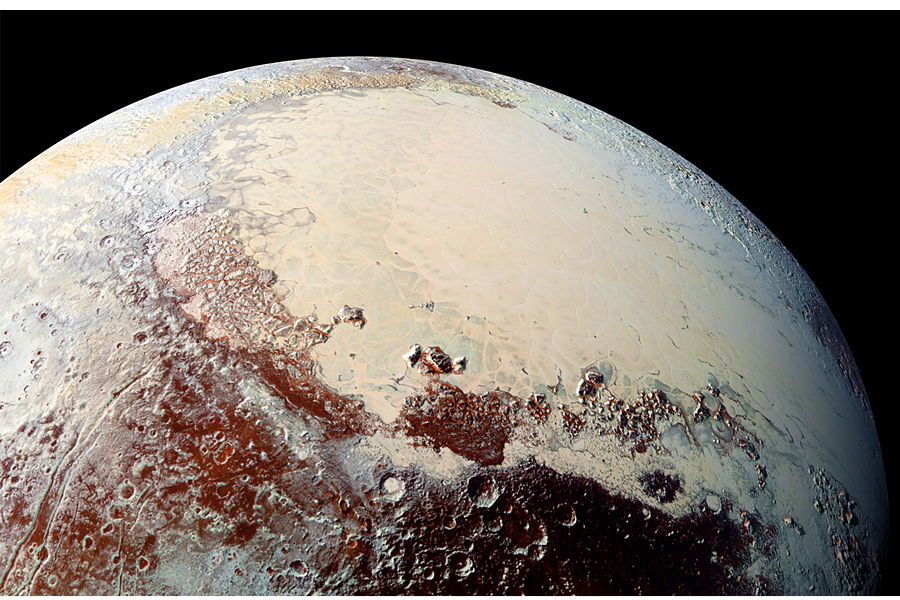

Mountains, plains, glaciers, a wispy atmosphere, and substantial color variation have appeared in images of Pluto captured by NASA’s New Horizons probe.

As the spacecraft has sent data back to Earth over the past couple months researchers have been dazzled by the spectacular images. This week scientists summarize their findings in a new paper.

Scientists on NASA’s New Horizons mission published their first paper on the Pluto system Thursday in Science.

“Pluto is a really interesting and geologically complex world,” Cathy Olkin, deputy project scientist on the mission, told The Christian Science Monitor in an interview. “It’s that diversity across this world that just makes it fascinating.”

The paper discusses a variety of findings on the data received from New Horizons thus far. The spacecraft captured a trove of data during its historic flyby in July and will continue to send data back to Earth for about a year.

Exotic ices and water ice

Researchers spotted mountains reaching as tall as the Rockies, says Dr. Olkin. And those mountains may contain water-ice.

Previous spectroscopic studies of the dwarf planet revealed the presence of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and methane ices. But “those would be too soft to retain the sharp shape that we have on those mountains on Pluto,” Olkin says.

Instead, water-ice must be present in a sort of bedrock on the planet. Thus, “the observed N2, CO, and CH4 ices must only be a surface veneer above this bedrock,” the researchers write in the Science paper.

That “veneer” may form part of one of the most distinct features on Pluto: the heart.

During New Horizons’ approach to Pluto, the spacecraft captured a picture that appeared to show a heart-shaped feature on the dwarf planet. Now called Tombaugh Regio, the region is bright, highly reflective and contains seemingly flat plains.

Those plains, forming the western half of the heart, have been dubbed Sputnik Planum.

And right smack dab in Sputnik Planum is a large glacier.

“On Earth we have glaciers,” Olkin says. “On Pluto there are glaciers, but they’re very different types of glaciers.”

Pluto’s glaciers seem to made of exotic ices, like frozen carbon monoxide, methane, and nitrogen.

“A lot of that difference is driven by the temperature,” Olkin explains. “Pluto’s surface temperature is approximately -390 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Characteristic of glaciers is their ability to slide, slowly. “Water ice wouldn’t flow at the temperatures of Pluto,” Olkin says. But the softer exotic ices would.

The researchers also spotted cellular, polygonal shapes in the ice. “The question is, what is causing those shapes,” says Olkin. The dominant idea is convection, with deep heat pushing at the ice from beneath.

Olkin describes it like cooking oatmeal. The heat underneath the pot will cause upwellings in the oatmeal. “It can make patterns sort of like we’re seeing in the ice,” she explains. So, perhaps there’s heat beneath the surface of Pluto.

A history of bombardment, active geological processes

A resident of the Kuiper Belt, a distant region of our solar system containing many comets, asteroids and other small, icy space objects, Pluto has likely encountered other small celestial bodies.

The researchers looked at the frequency and distribution of impact craters across the dwarf planet, compared with estimates of bombardment from the Kuiper Belt.

Based on the frequency of impact craters, they determined that other terrain-shaping processes must have been quite active within the past few hundred million years too. And Pluto’s surface could still be undergoing such changes, the scientists write in their paper.

“Such resurfacing can occur via surficial erosion/deposition (as at Titan), crater relaxation (as at Enceladus), crustal recycling or tectonism (as at Europa), or some combination of these processes,” they write.

Stunning color on the dwarf planet

Much like Earth, Pluto has a blue sky. That color comes from molecules that scatter light in blue wavelengths. Tholins, the complex organic molecules, also give color to other aspects of the dwarf planet.

Those same particles may fall to the surface of Pluto, making the dwarf planet red. Tholins are actually a range of reddish colors. The blue hue of Pluto’s sky comes from the way they scatter light in the atmosphere.

A blurry speck turned spectacular world

The discovery of Pluto was the result of a hunt for a ninth planet early in the 20th century. Astronomers noticed that the orbits of Uranus and Neptune were a bit irregular, possibly caused by another significant celestial body.

Although Pluto was first photographed in 1915, researchers did not recognize the object for what it was. They expected to see a brighter object than the faint speck that was the dwarf planet.

When Clyde Tombaugh finally confirmed Pluto’s existence in 1930, it was named by 11-year-old Venetia Burney. Named after the Roman god to the underworld, Pluto was initially labeled a planet.

New Horizons launched in January 2006, just months before the International Astronomical Union demoted Pluto to "dwarf planet" status, in August 2006.

Before New Horizons, scientists knew a few things about Pluto. In 1978 an astronomer discovered Charon, Pluto’s largest moon. The four smaller moons in the system were discovered in the 2000s, with the last found in 2012.

They also knew that Pluto has an atmosphere and saw a surface pressure change in the atmosphere between 1988 and 2002, according to Olkin. They had also detected nitrogen and carbon monoxide on the surface from previous observations.

But New Horizons has brought Pluto into far sharper focus.

“The best image that we have of Pluto before New Horizons was just kind of a blur,” Olkin says. That image was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

“It’s been very interesting to see the details on the surface and the complexity in this world” right in our solar system, says Olkin. “It’s like exploring your neighborhood.”