Pluto: young at heart, with fresh surface features

Loading...

Pluto has a surprisingly youthful heart — the smooth, round region on the dwarf planet's surface is no more than 10 million years old, a blink of an eye in the 4.5-billion-year lifetime of the solar system.

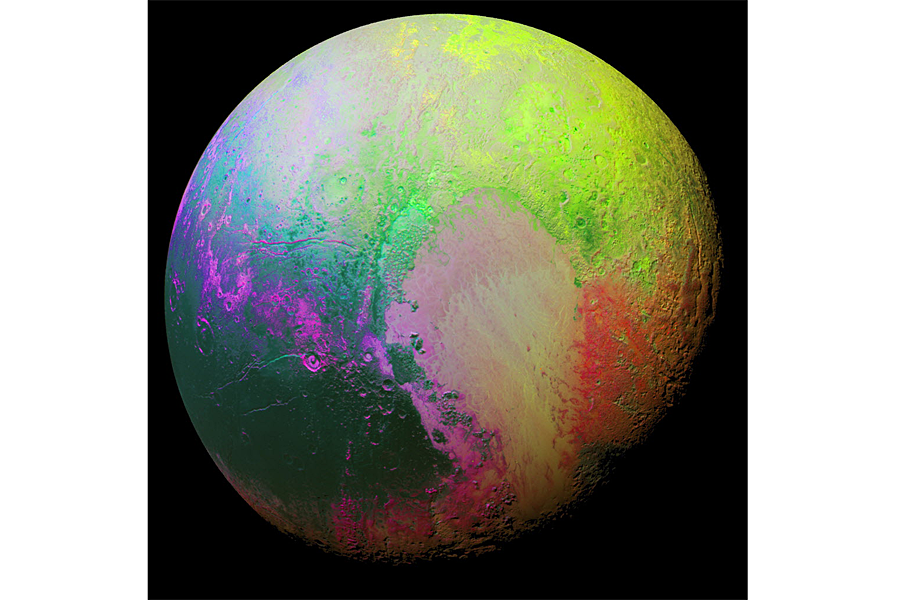

The large, western lobe of the "heart" on Pluto's surface is also known as Sputnik Planum, and it is strikingly free of craters. This suggests that geologic processes recently smoothed the region over. Researchers with NASA's New Horizons mission said this is surprising, because such processes require an internal heat source, which is often lost in small bodies like Pluto.

"It's a huge finding that small planets can be active on a massive scale, billions of years after their creation," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) in Colorado, said on Monday (Nov. 9) at the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting in National Harbor, Maryland. [See more amazing Pluto photos from New Horizons]

The New Horizons team announced several major findings at the meeting. Besides age estimates for other regions of Pluto, the scientists announced new information about the dwarf planet's hazy, surprisingly small atmosphere; the discovery of what may be ice volcanoes on Pluto's surface; and evidence that Pluto's four smallest moons are spinning around the dwarf planet in "pandemonium."

"Born yesterday"

When NASA's New Horizons mission arrived at Pluto last July, scientists were surprised to find evidence that the dwarf planet had been resurfaced in its recent history, most likely by recent geological activity.

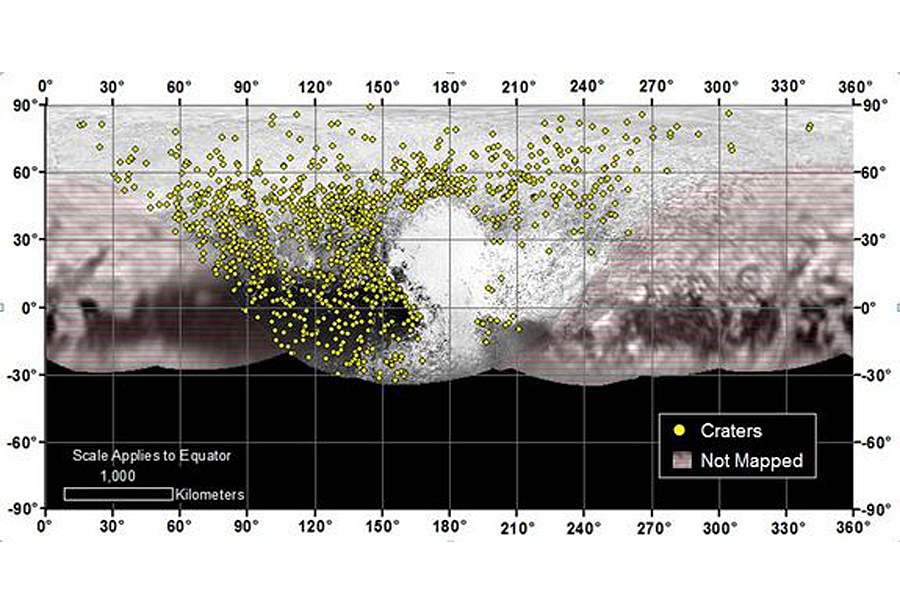

Because the surface of a planetary body doesn't come with a birth certificate to indicate its age, astronomers rely on techniques such as crater counting to estimate how long features have been around. The more heavily cratered an area is, the older it is expected to be, because processes such as glaciers, landslides, earthquakes, wind storms and volcanism can smooth over craters, creating a newer surface layer. Like wrinkles on people, a greater number of craters can indicate a region's advancing age.

One of the most surprising finds was the relatively smooth appearance of Tombaugh Regio, the "heart" of Pluto. On Monday, Stern announced that despite persistent examination, the New Horizons team hadn't found a single crater on Sputnik Planum, the western lobe of the heart. As a result, the estimated age for the area is no more than 10 million years old (and possibly even younger), scientists said.

"It was born yesterday," Stern said.

But just because one part of the planet has been recently refreshed doesn't mean the rest of it is just as young. Based on cratering counts, the eastern region of Tombaugh Regio is estimated to be about a billion years old, postdoctoral researcher for New Horizons Kelsi Singer, also of SWRI, said during a news briefing on Monday (Nov. 9). The region informally known as Cthulhu and the northern and midlatitudes, with their densely packed craters, are about 4 billion years old.

"We see a really wide range of ages," Singer said. "This tells us there's been ongoing activity throughout the years."

The higher ages also mean that Pluto itself must be at least around 4 billion years old, Stern said. Previous hypotheses suggested the dwarf planet could be a relatively new object that still had heat from its core driving its geological activity. Scientists had expected that heat to be lost if Pluto was an old object. But New Horizons revealed an active surface on an old planet, and internal heating is the best current guess for what's driving that activity — even if scientists don't quite know how that heat has lasted over 4 billion years. [How Was Pluto Formed?]

"We can't appeal to a young Pluto-Charon system to explain energy sources," Stern said.

Windy, but no chance of rain

The hazy atmosphere of Pluto, revealed earlier this year by New Horizons images, also surprised scientists. Now, researchers say the atmosphere surrounding the dwarf planet is colder and more compact than they had anticipated. Originally thought to billow out from the surface to create a bubble nearly seven to eight times larger than Pluto itself, the extended atmosphere is only about 2.5 times larger than Pluto, the new observations show. That's still significant, but far more compact than was expected.

"This changes our thinking of the long-term evolution of Pluto and its atmosphere and its ices," said Leslie Young, New Horizons deputy project scientist.

Randy Gladstone, a New Horizons co-investigator from SWRI, told Space.com that the layers of hazes suggest that the upper atmosphere of Pluto is "stagnant" and free of winds. However, a kilometer or two above the surface, winds could play a role in shaping the landscape, he said. Some scientists have suggested that winds could have helped to mold the puzzling "snakeskin'" terrain, which has no exact, known analogue anywhere else in the solar system.

Gladstone said it is more likely that the strange appearance formed as nitrogen and methane ices in the dwarf planet's crust changed directly from a solid to a gas. However, he notes that the region vaguely resembles wind-erosion patterns seen in deserts. If the surface material was soft, then high-speed winds could have helped to erode the region, he said.

"There's a lot of weird things happening near the surface that we don't understand yet," Gladstone said.

Scientists can help determine how these features formed by using a variety of models to try to create them under Pluto-like conditions.

"If they say the only way we can get snakeskin blades is by wind erosion or sandblasting, then it will be evidence for Pluto being different," Gladstone said.

In some ways, the atmosphere of Pluto resembles that of Saturn's moon Titan, with hazes dominating both worlds. On Titan, ionized particles come together to form larger charged particles in the upper atmosphere. Gladstone said that similar things may be happening on Pluto.

But while clouds on Titan rain methane, don't look for similar weather patterns on the distant dwarf planet. Gladstone said there is "no chance" of rain on Pluto, due to its thinner atmosphere.

Since the July 2015 flyby, New Horizons has sent back only about 20 percent of its data to Earth. The remaining observations will continue to arrive over the next year, providing more information about the world at the outer edges of the solar system.

"Once again, Pluto is giving us a new view of how small planets operate over their lifetime," Young said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

- Pluto's 5 Moons Explained: How They Measure Up (Infographic)

- Photos of Pluto and Its Moons

- Pluto: A Dwarf Planet Oddity (Infographic)

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.