How calculating the gravity on distant stars could tell of habitable planets

An international team of astrophysicists has devised a way to measure the surface gravity of distant stars to help determine if the planets in their orbit are hospitable to life.

Led by a researcher at the University of Vienna, the team calculated the surface gravity of stars that are too distant to study with conventional methods by looking at the slight variations in their brightness, which is caused by convection and surface turbulence, the same forces behind a pot of boiling soup, explains the Vancouver Sun.

Gravity is crucial to many aspects of astrophysics, say the researchers in a paper published on January 1 in the journal Science Advances, as it provides clues to the properties of stars, such as their mass and radius, and to the properties of planets in their orbits that might make them habitable.

“Our technique can tell you how big and bright is the star, and if a planet around it is the right size and temperature to have water oceans, and maybe life," said study co-author Jaymie Matthews, a professor of astrophysics at the University of British Columbia, in a study announcement.

"If you don't know the star, you don't know the planet," explained Prof. Matthews. "The size of an exoplanet is measured relative to the size of its parent star. If you find a planet around a star that you think is Sun-like but is actually a giant, you may have fooled yourself into thinking you've found a habitable Earth-sized world."

To determine the gravitational pull of distant stars, the researchers used data of star brightness collected from Canada's MOST and NASA's Kepler satellites.

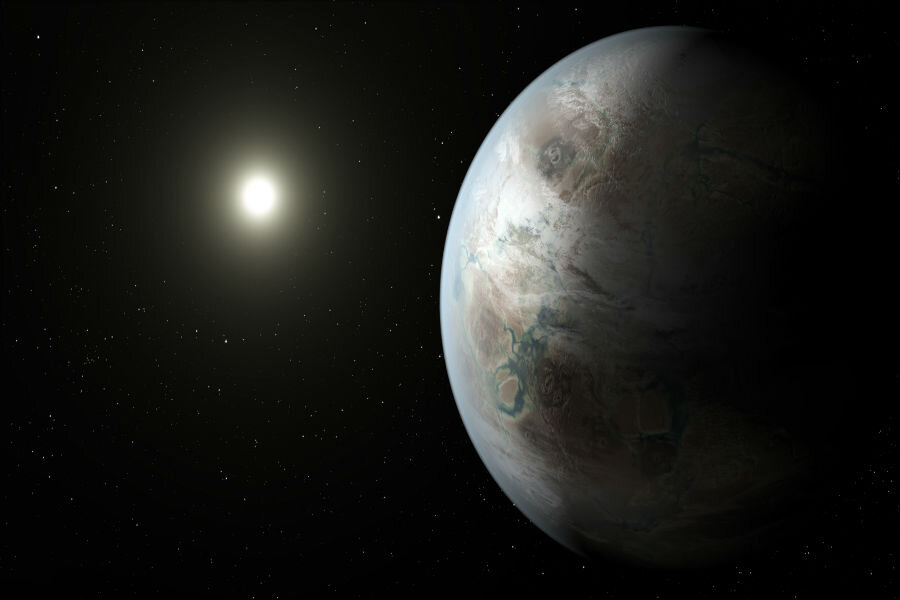

Since its launch in 2009, Kepler has already discovered more than 1,000 planets, a dozen of them less than twice the size of Earth and residing in the habitable zone of their host stars, which means these planets orbit their host stars at the right distance to make them neither too hot nor too cold to harbor liquid water. Astronomers believe the presence of water on planets is critical to life.

The team of astrophysicists behind the latest gravity-measuring technique believes that it will help future exoplanet surveys to correctly characterize the planets they find.

“I expect someone will announce the discovery of life on an exoplanet within about 20 years,” Matthews told the Vancouver Sun.