Astronomers spot brightest supernova in history

Loading...

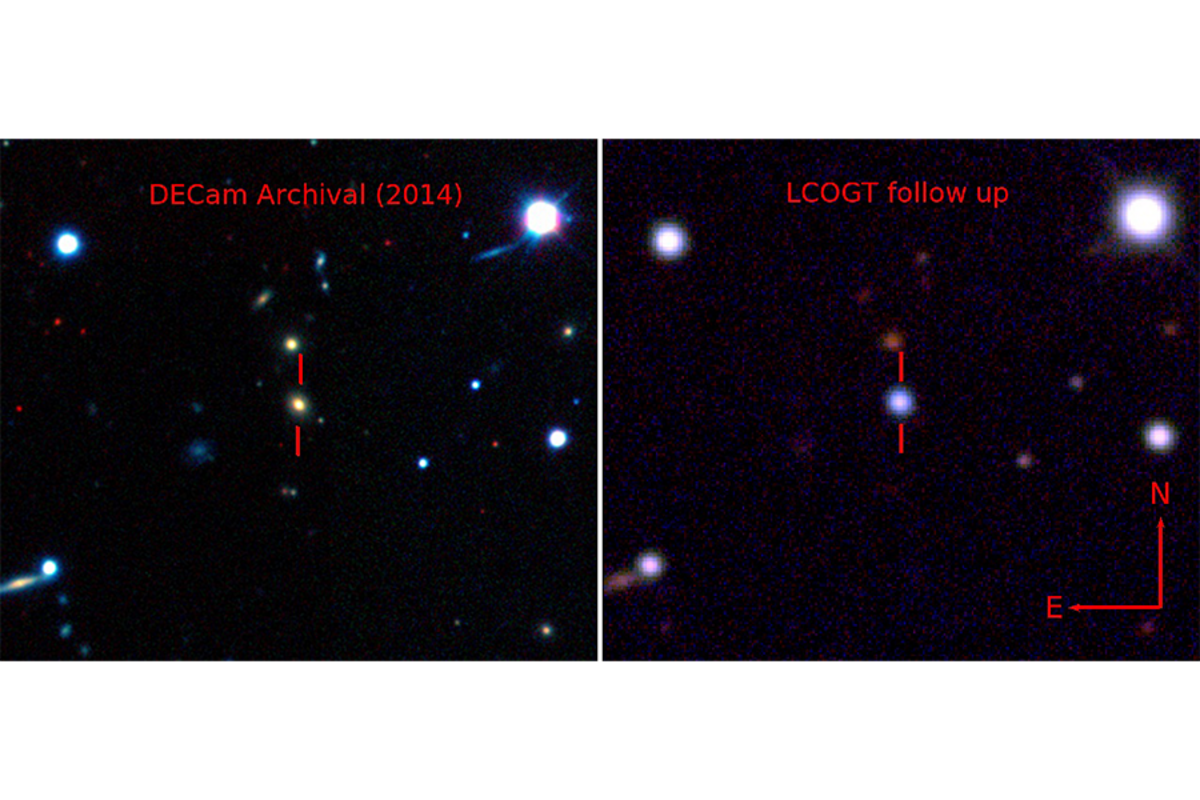

Astronomers have spotted a supernova twice as luminous as any yet observed, and at its peak 50 times brighter than the entire Milky Way.

The star, affectionately named ASAS-SN-15lh, falls into the category of super-luminous supernovae (SLSNe), exploding stars that shine 100 to 1,000 times brighter than regular supernovae.

Its location has excited astronomers just as much as its luminosity: located in an unusual kind of galaxy, the supernova could shed important light on this little-understood group of celestial superstars.

"We are continually discovering the unexpected and these discoveries sometimes force us to change both what we think can happen, and our understanding of objects we have already seen," Ben Shappee, one of the astronomers who made this latest discovery, tells The Christian Science Monitor. "Nature is extremely clever and it is often more imaginative than we can be."

Super-luminous supernovae were first discovered within the past two decades, and there is now a global network of telescopes that hunts for them every couple of nights, called the All-Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae system, the international collaboration responsible for the latest discovery.

A supernova is the largest kind of known explosion to take place in space, and one of the brightest objects ever to assail the skies.

This latest addition to the family of SLSNe was found in a relatively large calm galaxy, whereas most of its brethren make their home in smaller galaxies that are busy churning out stars.

In trying to understand the intensity of ASAS-SN-15lh, astronomers compare its characteristics to those of dimmer SLSNe poor in hydrogen.

The brightness could be explained by the presence of a magnetar, a neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field. But Dr. Shappee, part of the team that discovered ASAS-SN-15lh, is doubtful:

"The astounding amount of energy released by this supernova strains the magnetar-formation theory," he explains. "More work will be necessary to understand this extraordinary object's power source and whether there are other similar supernovae out there in the universe."

An alternative theory is that the exceptional luminosity is powered by vast amounts of decaying nickel.

Supernovae are usually observed in galaxies other than our own, but they do exist in the Milky Way; they are simply hard to see because of the dust blocking our view.

Johannes Kepler claimed the discovery of the last supernova in our galaxy visible to the naked eye, in 1604. Since then, astronomers have had to rely on instruments such as NASA’s Chandra telescope, which in 2008 identified the remains of a star that exploded about 140 years ago.

These blinding events happen in one of two ways, as explained by NASA.

First, in a system where two stars orbit the same point, one of the stars, known as a white dwarf, steals matter from its partner. But its theft is excessive, too much matter accumulates, and it explodes – a supernova.

The alternative scenario involves a star coming to the end of its life. Its nuclear fuel is depleted and some of its mass is drawn into the core. As the star’s center becomes unsustainably heavy, unable to withstand its own gravitational force, it collapses into the astounding exhibit of an exploding star.

As for super-luminous supernovae, the class of ASAS-SN-15lh, they are ironically difficult to spot, forming in the low-luminosity busy galaxies as they do. But perhaps the latest discovery, being in quite a different galaxy, will give astronomers fresh pointers as to where to focus their quest.

At the very least, astronomical breakthroughs like this one give meaning to the profession. "Discoveries like this are the reason I am an astronomer," says Shappee.

[Editor's note: The original article stated the incorrect photo credit.]