Scientists find 'exquisite' 515-million-year-old fossilized nervous system

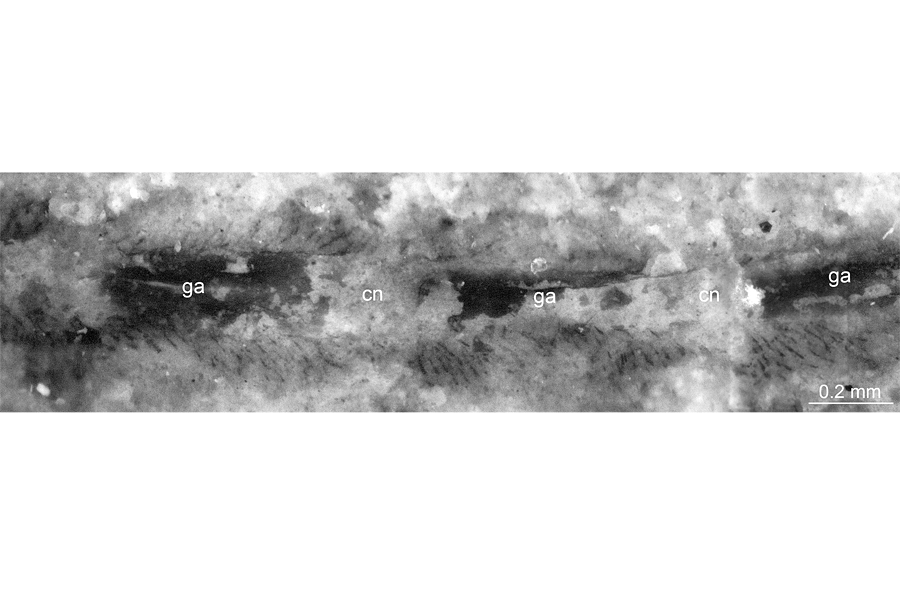

A bluish line dotted with dark splotches runs through newly discovered arthropod fossils from the early Cambrian period. Tiny, thin lines splay out from the black masses.

Scientists say this is an ancient, well-preserved example of a complex anatomical structure: the nervous system.

"Because nervous systems are extremely rare in the fossil record, finding one is extremely informative about the early evolution of these animals," study co-author Javier Ortega-Hernández tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

Researchers reported their findings in a paper published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

These fossils found in China "are unusual and important because they reveal exquisite details of the nerve cord in ancient animals that are over 500 million years [old]," writes Mike Lee, of Flinders University and the South Australian Museum, who was not part of the study, in an email to the Monitor. "These fossils reveal how the nervous system has evolved, over a period of 500 million years."

The preserved animal, called Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis, lived some 515 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion when many major groups of animals emerged during a short, fast period of evolution. As such, studying fossils from this period could tell researchers a lot about early animal evolution.

The fossil is an arthropod, an invertebrate animal with an exoskeleton, segmented body and jointed limbs. Animals such as spiders, crabs, centipedes, lobsters, cicadas, and other insects also fall in the phylum arthropoda.

But what makes this discovery interesting to researchers is that the fossilized nervous system is unlike those found in living arthropods. The recent arthropods have fewer individual nerves clustered around each individual ganglion – the dark blobs that form the ventral nerve cord. Instead, the ancient animal's nervous system looks more like those of other animals such as velvet worms, Onychophora, which are cousins to arthropods, but, without a hard exoskeleton, they are not arthropods themselves.

"What this is showing is that this particular fossil is in a type of intermediate state in between something that looks like an Onychophoran and something that looks like a living arthropod," Dr. Ortega-Hernández says.

He suggests that perhaps the living arthropods have a differently structured nervous system because they have more specialized features than their Cambrian ancestors. Ants, for example, have massive jaws and antennae. But Chengjiangocaris lived in a simpler world. There were fewer predators and less competition so the prehistoric arthropod didn't need to be as specialized.

These newly reported fossils aren't the first to be found with preserved parts of a nervous system from the early Cambrian. But this is the most detailed example of the ventral nerve cord, Ortega-Hernández says. The other fossils displayed more of the brain and less of the nerve cord itself.

Chengjiangocaris is a member of the order Fuxianhuiida, a group of arthropods that scientists place at the base of the arthropod family tree. Growing as long as 6 inches, Chengjiangocaris would have been on the larger size for animals 515 million years ago.

The animal would have lived on the seafloor and scuttled around a bit like a crustacean on as many as 80 pairs of legs. To eat, these organisms shoveled sediment into their mouths and then digested to extract nutrients.

"They had a relatively uneventful existence back in the day," Ortega-Hernández says.