These 12 lizards were trapped in amber for 99 million years

Loading...

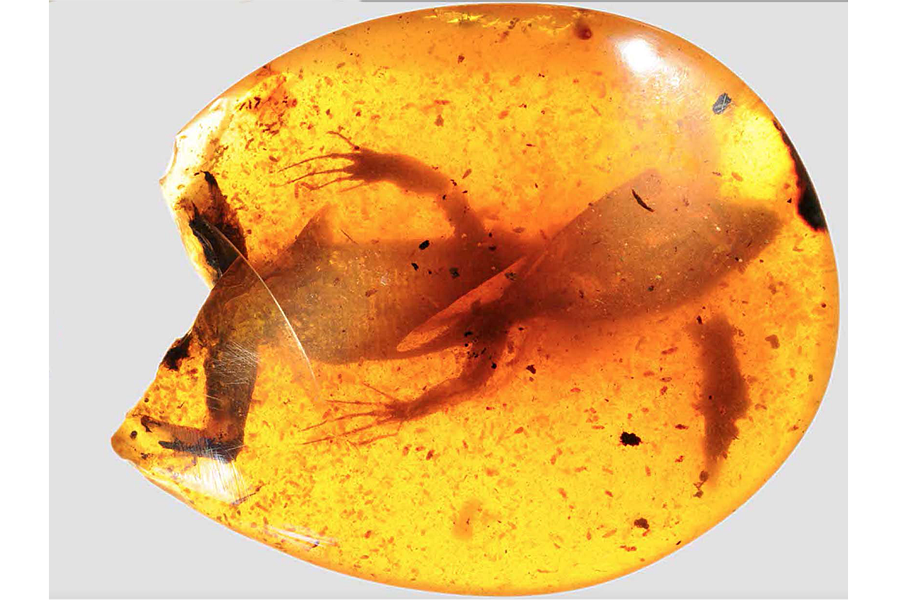

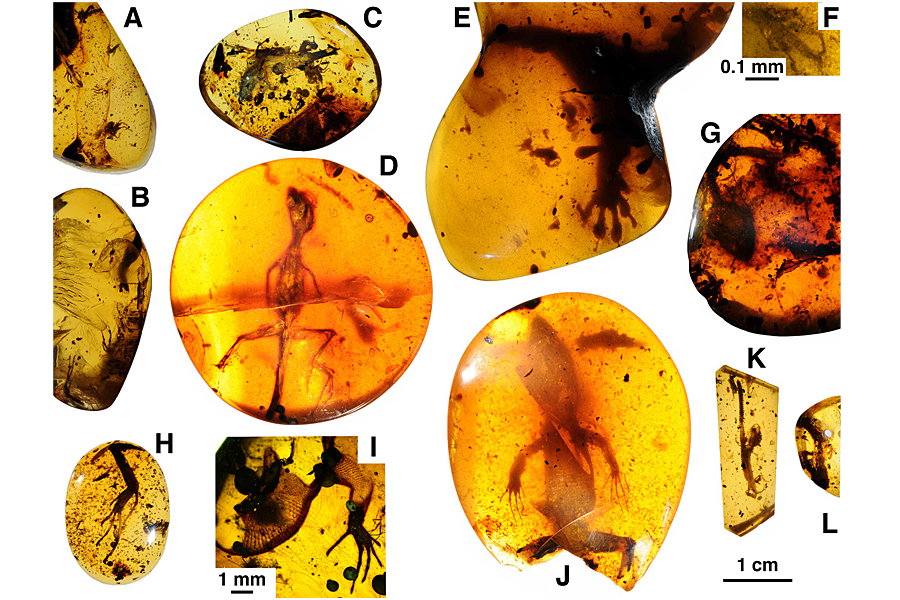

Some 99 million years ago, 12 unsuspecting lizards stepped or fell into sticky tree resin and couldn't tear themselves loose in the forests of what is now Myanmar. Over time that resin fossilized into amber, preserving the little lizards for scientists to study later.

Now, researchers are looking to these prehistoric golden chunks to better understand how lizards have evolved.

There was a diverse population of lizards living in the region at the time, the scientists report in a paper published Friday in the journal Science Advances. And they ran the gamut, with some quite similar to modern lizards – like geckos, wall lizards, and dragon lizards – and others like nothing known today.

"The assemblage is cool because it has some examples which are really, really modern and then others which are really, really old, and then others in between," study co-author Edward Stanley, a herpetology researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History, tells The Christian Science Monitor.

"In the amber we have things that are clearly gecko," says Dr. Stanley. The gecko-like prehistoric specimens have toe pads. Modern geckos use their toe pads to scale walls and perform other sticky-footed feats, but these prehistoric toe pads appear somewhat different.

Other amber-preserved lizard specimens had been found with toe pads more similar to those on living geckos, which suggests that "even 100 million years ago geckos apparently already had evolved a well-diversified subset of tools for clinging onto surfaces," Stanley says.

Another block of amber could show "some kind of animal that was on the road to becoming a chameleon," Stanley says. And that specimen, at less than half an inch long, had probably just hatched before it met its demise.

A CT scan of the itty-bitty specimen revealed a skeleton similar to those of modern chameleons but also with features more like other lizards. "It's this interesting sort of halfway stop between a modern chameleon and the sister group to chameleons, which are the dragon lizards," Stanley says.

This specimen doesn't have the fused digits that today's chameleons have to help them live in trees. But, like a chameleon, it has a shorter spine with fewer vertebrae than its cousin lizards. It also has a characteristically long hyoid bone, the long bone in chameleon's throats that they use to shoot their sticky tongues out at top speeds to capture unsuspecting prey.

These fossils can also offer other clues into the lizards' lives. Amber, because it is produced from tree resin, can only form in forested regions, so the animals must have been spending a lot of time around trees.

Amber can also preserve things when other processes cannot. The Myanmar forest amber is a good example because it's warm and moist in a tropical forest so things decompose quickly, Stanley explains. But something trapped in resin is not affected in the same way.

Amber is also good at preserving small things, like bits of plants, insects and other small animals, that might otherwise get lost in the fossil record. And it can preserve more of the organism, as it freezes it in place almost exactly how it lived, tissue and all.

How does it work?

"It's a process of natural fixatives in the resin," George Poinar, an entomologist at Oregon State University known for his research on amber fossils who was not part of this study, tells the Monitor. "[The resin] contains preservatives that enter into the tissue," he explains. "At the same time, the sugars in the resin withdraw moisture from the specimen." Those two processes preserve the tissue of the organism as the amber hardens around it.

Dr. Poinar, who admits to having a "fertile imagination," was intrigued by the fact that although there were many different types of lizards frozen in time, many of the specimens were incomplete. He proposes that perhaps the lizards were stuck in the resin in a mad dash to escape a carnivorous dinosaur looking for a tasty morsel.

In Poinar's scenario, vicious, agile, clawed dinosaurs chased the lizards up a tree. When the lizards became ensnared in resin, the hungry dinosaur would have snacked on them, leaving behind the parts that would mean also eating the sticky goop.

"This is just speculation on my part," Poinar says. But, he adds, it could explain why so many of these lizards appear to be tree-dwellers while many of them live on the ground today.