Mercury mystery: Why is the planet's surface so dark?

Scientists have long puzzled over the shade of the planet closest to the Sun. Mercury's surface appears remarkably dark, but why?

Thanks to data from NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft that orbited the planet from 2011 to 2015, researchers might have an answer.

A new analysis of the data identifies carbon, in the same form as the "lead" in a pencil, as the dark substance on the planet's surface. And this could mean that Mercury's original crust was made of graphite, scientists say in a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"We think that what we're seeing is the remnants of Mercury's original crust that formed 4.6 billion years ago," says study lead author, Patrick N. Peplowski, who researches MESSENGER data at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. And that ancient carbon-rich crust still darkens the planet.

Researchers had already proposed, as a theoretical explanation, that carbon was mixed into Mercury's crustal rocks. "When you think of charcoal or you think of pencil lead, it's really dark. So if there was a little bit of carbon mixed in with these materials, then that could easily account for the albedo," or how much light is reflected from a surface, explains Dr. Peplowski.

But there's very little carbon in the crust of the moon, Earth or other planets. "So if carbon was the darkening agent of Mercury, there had to be a whole lot more than we had ever seen in the crustal materials on another planet," he says.

And apparently there is.

So how did Mercury's crust get such a unique composition?

Peplowski and his colleagues suggest that it all started early in the formation of our solar system. When the planets were forming, they were really hot, Peplowski says. The terrestrial planets were so hot that an ocean of molten rock covered their surfaces. As the planets cooled, minerals would crystallize. Those that were most buoyant in a planet's magma ocean floated up and formed the planet's crust, while the other mineral crystals would have fallen down to be buried beneath the surface.

A paper published last year calculated that just one mineral would have floated in Mercury's magma ocean: graphite.

In this scenario, Mercury would have started out with a graphite crust. Over time, volcanic activity would have covered that graphite and formed the crust of the planet we see today.

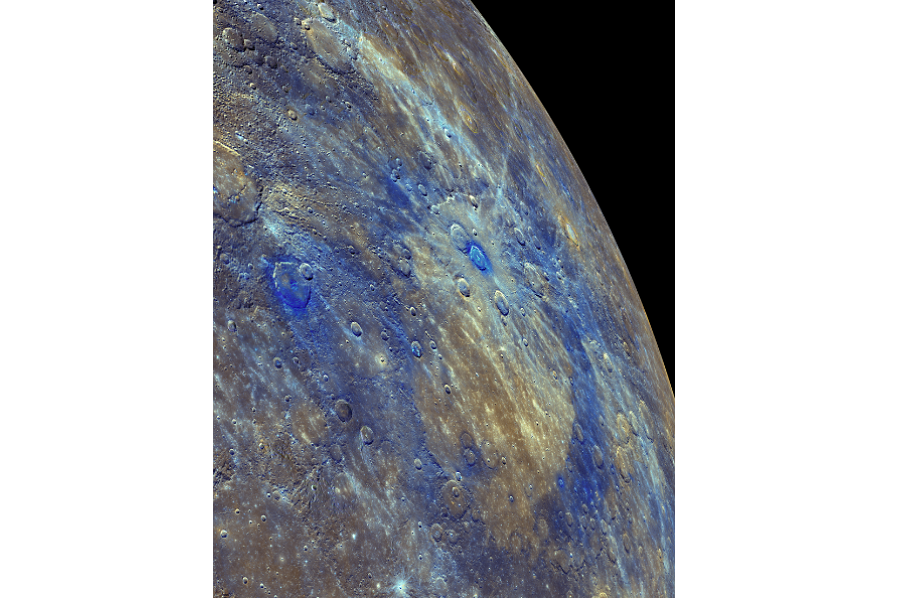

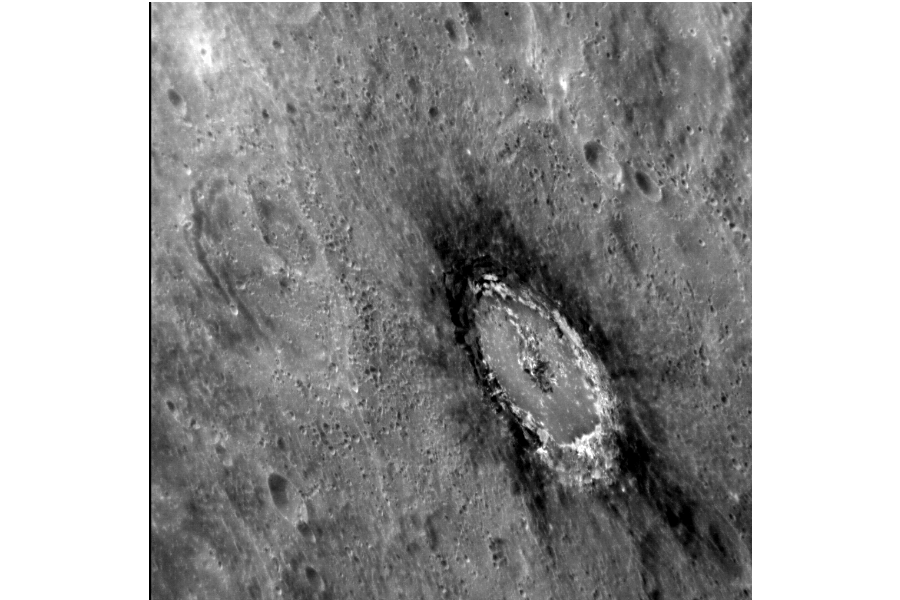

But that crystalized carbon didn't just disappear, it was mixed in with some of the crustal material, thanks to the impacts of space rocks, giving the whole planet a darker tone. And occasionally, when a meteor punches a deep enough hole into Mercury's surface to expose the original crust, an even darker splotch appears.

Mercury's darkness had long perplexed scientists. Some had suggested that iron was a darkening agent, like it is for our moon's dark patches. Carbon in the form of graphite was proposed, but since most other planets' carbon was presumably locked in their cores, it seemed unlikely.

Peplowski and his colleagues looked to MESSENGER data to test these hypotheses. "And we found three very compelling lines of evidence, all which only supported the graphite hypothesis," Peplowski says.

The scientists looked at the spectrum of light reflected, the X-ray data of the darkest regions, and the neutron radiation emitted from the surface of Mercury. In concert, these three methods narrowed the hypotheses down to one: carbon as a darkening agent.

If they're right, an original crust of graphite makes Mercury unique. "The other terrestrial planets had flotation crusts, but they wouldn't have been graphite," Peplowski says.

Carbon is a necessary ingredient for life, but that doesn't mean we might find extraterrestrial life on Mercury. Mercury is too close to the Sun, too hot and has other factors likely to eliminate it as a habitable planet. But understanding how much carbon is there could give scientists insight into the amount of carbon that was around during the formation of our solar system.

"There's so much carbon, it's so different from other planets that it forces us to stretch the boundaries of our understanding of how the solar system formed," Peplowski says.