Earliest evidence of exoplanets came to light in 1917

Loading...

When astronomers used the largest telescope in the world in 1917 to survey a nearby white dwarf star, they made a recording of the light emitted, casually indicated the star looked a bit warmer than our own sun, and archived the recording.

Unknowingly, they had also captured the earliest known observational evidence of planets existing around other stars, or "exoplanets."

But it's taken almost a hundred years and teamwork spanning several generations to make the "rediscovery." Carnegie Observatories finally brought the historical plate out of storage and into the scientific limelight in a press release Tuesday, noting "You can never predict what treasure might be hiding in your own basement."

The rediscovery is "a recognition of something that has gone unrecognized for almost 100 years," Jay Farihi, the Ernest Rutherford Fellow at University College London, told The Christian Science Monitor via phone interview. "It's a historically significant find."

The process of rediscovery began years ago with Dr. Farihi and his PhD advisor, Prof. Benjamin Zuckerman, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Los Angeles. As part of his research, Farihi was writing a review article about planetary systems surrounding white stars, which was later published in New Astronomy Reviews.

He realized that a white dwarf known as van Maanen's star was surveyed in 1917 by Walter Adams, the director of Mount Wilson Observatory, which was formerly a part of Carnegie. Those glass plates, Professor Zuckerman told him, might contain the earliest evidence of exoplanets.

The news launched Farihi into an ever deepening investigation. "I got it into my head that someone should go and dig this up and actually let's look at it and let's see it," Farihi says.

Last year, with the help of current Carnegie Observatories' Director John Mulchaey, the plate was located in the archives and made available for Farihi to inspect.

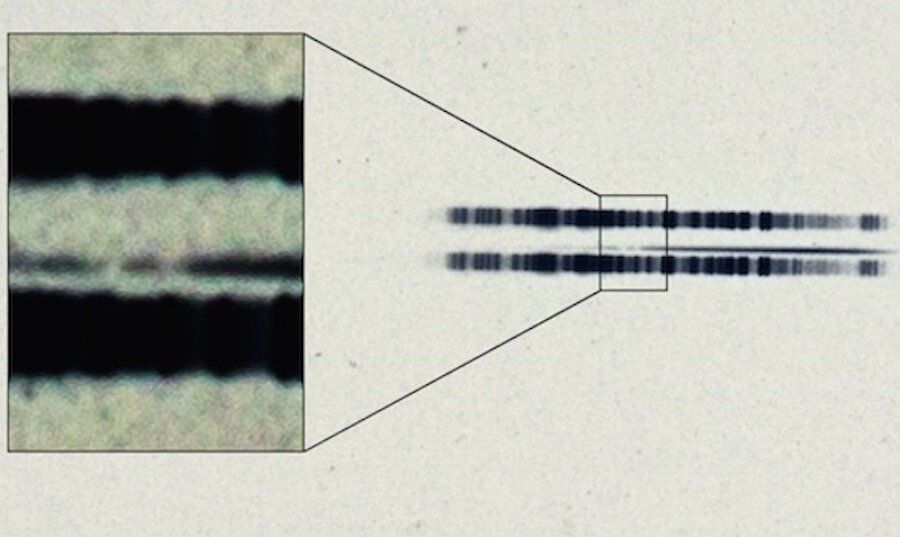

The recording of light emitted from a star, or a stellar spectra, allows scientists to determine the chemical composition of the star and how the light has been affected by objects it passed through while traveling to Earth.

By looking at the spectrum (shown in the image above), Farihi was able to notice two missing fangs in the thin line, which indicates calcium is present in the star: a common occurrence in most stars, but a big deal for a white dwarf.

As white dwarfs naturally only contain helium and hydrogen, the presence of calcium requires the star to be contaminated by an external presence, the rocky debris that accumulates during the formation of planets.

Farihi confirmed that the recording had all the evidence required to indicate the existence of exoplanets around a white dwarf nearly a century before it became clear to modern astronomers.

So why didn't scientists in 1917 make the connection?

"It could have been done 99 years ago, but they didn't have the required understanding of astrophysics," Dr. Mulchaey, the Observatories director, told the Monitor.

Astronomy was a very different science a century ago. Rather than finding and pushing the boundaries of astrophysics and our current understanding of how the universe works, astronomers of the past were more focused on identifying and categorizing celestial objects.

Early 20th century astronomers wouldn't have linked the calcium in the white dwarf to planetary debris and exoplanets.

But for modern astronomers, the calcium is supporting evidence for the existence of exoplanets. It's indirect evidence, but pretty conclusive, according to Farihi.

"To get these [big debris] you really have to build planets. It's a runaway formation process," Farihi said. "Once things get that big, planets are unavoidable."

Currently, scientists can see the rocky debris and asteroids orbiting close to van Maanen’s star in infrared and are using direct imaging and transit methods to find direct evidence of the exoplanets.

In the meantime, scientists are looking at the rediscovered stellar spectra as historically significant – the earliest evidence of exoplanets, and a lesson about astronomy as a science.

"You can have the best telescope in the world and not have the knowledge to make the discovery," Mulchaey concluded.