Peacock-feather physics: How this "train-rattling" display might woo potential mates

A peacock's efforts to woo a mate can be downright feather-shaking.

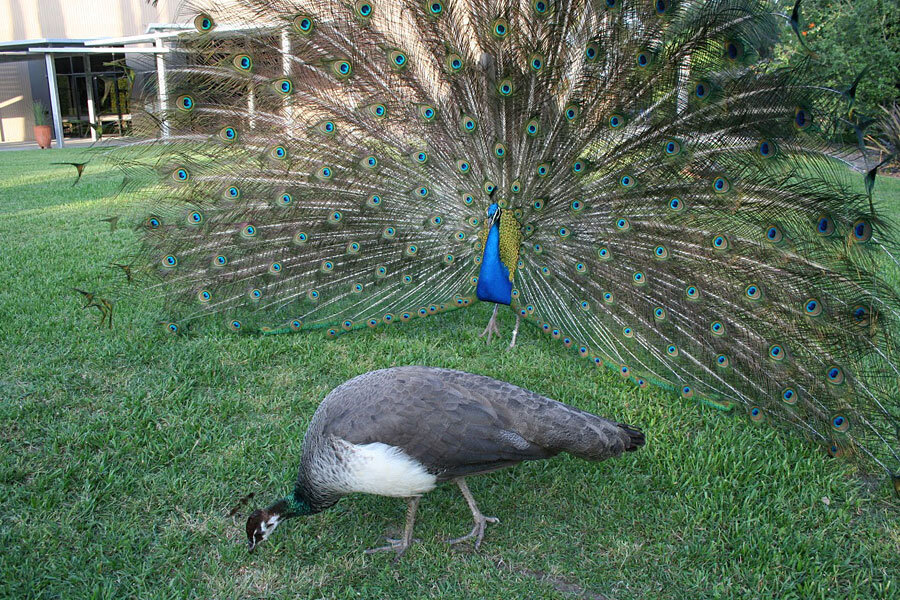

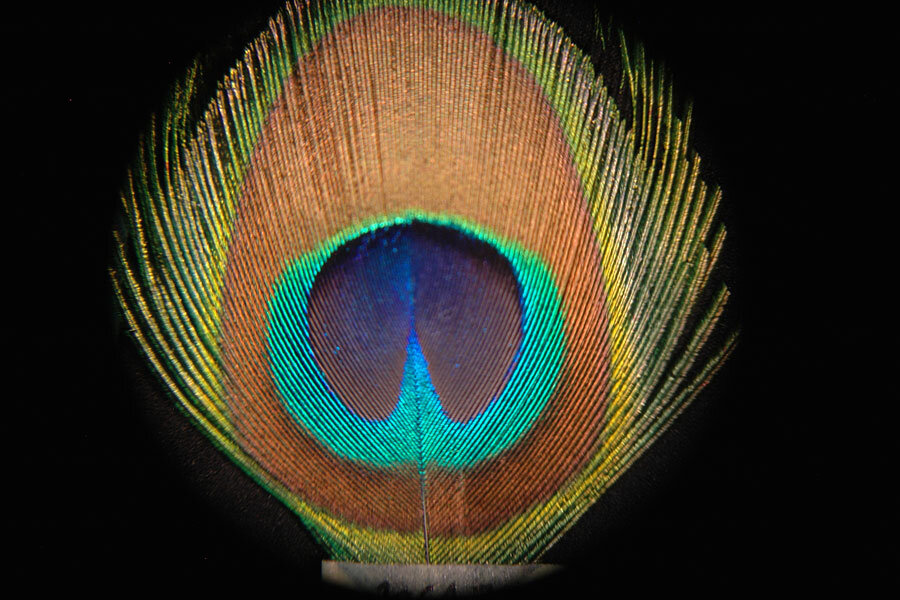

When the colorful birds try to attract a female, they shake and rattle their fanned-out train feathers, a motion that shows off the shimmering, iridescent eyespots that dot their spectacular train. But until recently, scientists knew little about the physics of this iconic display.

It turns out, peacocks use their shorter tail-feathers to strum the long train feathers like a guitar, creating vibrations at resonance. These vibrations, combined with tiny structures within the feathers, help create the illusion that the feathery eyespots are hovering in place over a moving background, according to a paper published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE.

"When the peahen is close to a peacock, his huge fan of feathers could practically fill her field of view," study author Roslyn Dakin, a researcher at the University of British Columbia, tells The Christian Science Monitor in an email. "And when he starts to wiggle those feathers, most of what she would see is moving, except for the eyespots floating on top."

How exactly does he do that?

A peacock makes his eye-spotted feathery fan quiver in a "train-rattling" display by wagging his tail. As his tail feathers strum across his train feathers, the whole fan vibrates.

But this shaking doesn't spread uniformly across these long feathers. When the research team stuck the feathers under a microscope, they found that microhooks keep the peacocks' iconic eyespots latched together through this dance. The feather filaments around the eyespots sway along to the strumming while the center of the eyespots remain more stationary.

This makes the eyespots pop out as more iridescent, something Dr. Dakin's previous research found correlated with the amount of matings a peacock was able to achieve.

The team also found that this train-rattling occurs at resonance, meaning the strumming that keeps the tail-feathers shaking happens at a frequency close to or at the feathers' natural frequency.

It's like pushing a child on a swing, explains another study author, Suzanne Amador Kane, an applied physicist at Haverford College, in a phone interview with the Monitor.

"If you just pull them back and let them go, they swing at a pre-set frequency. The rate at which they swing back and forth is set by the mechanical properties of the swing and not how you're pushing them," she says. "So if you want to push them effectively and not waste your energy, you give them one push every time they swing back toward you."

When you're pushing them in sync with that natural frequency, that's resonance, Dr. Amador Kane explains. So the peacocks are strumming their tail feathers at just the right rhythm to match their train feathers' natural frequency, which is dictated by the physical properties of those feathers.

This resonance creates a reverberating mechanical sound, but it also suggests that this display is energetically efficient.

The researchers studied this train-rattling display by capturing high-speed video footage of peacocks during mating season. Then, they shook individual feathers in the lab at different frequencies to determine their natural frequency. That's how they determined the feathers were strummed at resonance.

This study illustrates that "the display is not a simple showing and gentle shaking of the feathers," writes Rebecca Kimball, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Florida who was not part of this study, in an email to the Monitor.

The rhythmic performance seems to be an attempt to attract a peahen's attention, but just what the females see in the biomechanical feat is still unknown.

"It could be that the males with the most powerful muscles perform the best displays. Or, it could be that males with the best endurance, or the most energy to spend, perform the best. Yet another possibility is that the peahens don't really care about vibration – maybe it gets their attention, but they don't use it when deciding who to mate with," Dakin says. "It could all just be noise, as Darwin suggested."

Dr. Kimball suggests that understanding the biomechanics could help "drive new studies that do a more critical assessment of what females look for in males."

"Peacocks have been the focus of much study due to their impressive feathers and the visual display of their tail which impresses all of us. However, previous research has focused on the size, number, and color of the feathers," she says, but this study suggests that "there may be much more complexity in what females look at in these displays than has been recognized previously."

"While this study cannot address why there may be so many different types of signals in peafowl, it emphasizes that even for species we think of as 'well-studied' we still have a lot to learn," Kimball says.