Beyond Pluto: What New Horizons found in the Kuiper Belt

NASA’s New Horizons probe recently documented the first object it has passed since its historic Pluto flyby this past July.

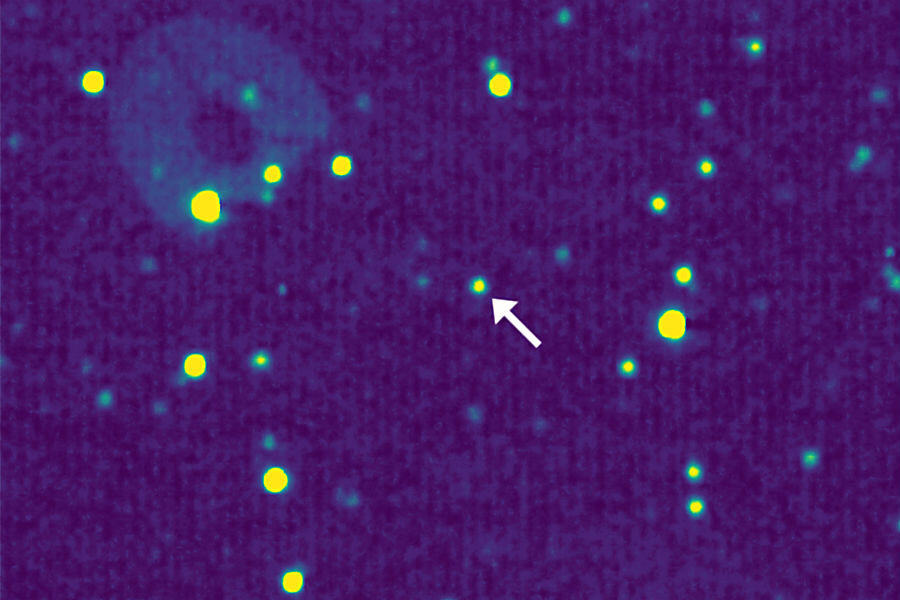

NASA announced Thursday New Horizons’ recording of 1994 JR1, a 90-mile Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) currently orbiting 3 billion miles from the sun. The space probe was able to capture 1994 JR1 using its on-board Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) from a distance of 69 million miles away. NASA said the LORRI instrument caught the KBO twice on April 7 and 8, breaking the record for the closest view of a KBO - set by a New Horizons observation of 1994 JR1 late this past year, from approximately 170 million miles away, which at the time set its own record for closest KBO picture.

The first of the space agency’s New Frontiers missions, New Horizons will send back data from its encounter with Pluto through this year as it continues on its path to fly by the KBO 2014 MU69 in January, 2019.

While the find represents a milestone for New Horizon’s observational capacities, it also provided researchers insight into 1994 JR1 and other KBOs. Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) scientists were able to place the minor planet in its region in space more accurately than ever before using a composite of the previous two JR1 sightings.

“Combining the November 2015 and April 2016 observations allows us to pinpoint the location of JR1 to within 1,000 kilometers (about 600 miles), far better than any small KBO,” said SwRI New Horizons team member Simon Porter said in a joint release. The new information allowed the team to dispel a previous theory that JR1 is a Plutonian quasi-satellite, and learn more about its rotation period.

By analyzing light curve information taken from JR1, measuring the changing intensity of light reflected off of the KBO, scientists were able to confirm the length of a day on 1994 JR1: 5.4 hours. In comparison, Pluto’s rotational period lasts slightly less than 6.4 days, nearly 30 times longer than its Kuiper Belt neighbor.

“That’s relatively fast for a KBO,” team member John Spencer said of JR1's day.

Mr. Spencer also said in the NASA release that observations of objects like JR1 are good preparation for the New Horizons team ahead of potential flybys of other KBOs on the probe’s path to an ultra-close look at 2014 MU69. On that path, he said the craft could image around 20 KBOs from closer than the recent JR1 pictures were taken.

“This is all part of the excitement of exploring new places and seeing things never seen before,” Spencer said.

Looking at KBOs allows scientists a new perspective on the previously elusive bodies, which generally “haven’t been disturbed” in space since their formation, according to Mr. Porter in Popular Science. Data streaming back from New Horizons’s Pluto pass has already granted insight into the former planet’s geological activity and surface variation otherwise inaccessible to researchers on Earth.

The New Horizons team in April submitted a proposal to NASA which, if approved, would extend the probe’s mission through 2021 and cover an additional 2 billion miles through the edge of the solar system.