How a Japanese company seeks to create artificial meteor shower

Loading...

A Japanese company is looking to combine atmospheric study and entertainment with its Sky Canvas Project, which it hopes can generate a satellite-based artificial meteor shower for the 2020 Summer Olympics, held in Tokyo.

Star-ALE, the developer of the Sky Canvas light show proposed for the opening ceremonies of the Olympic games, hopes its artificial shooting stars will support future astronomical projects in Japan.

“This type of project is new in the sense in that it mixes astronomy and the entertainment business,” Star-ALE founder and chief executive officer Lena Okajima said in her corporate profile. “These shooting stars that are born through science function as a high-profit entertainment business, and the resulting funds will serve to further advance fundamental scientific research.”

Visible shooting stars are the result of objects falling through Earth’s atmosphere, where they heat up and burn, producing the bright displays visible from the ground. While meteor showers such as the annual Perseids are relatively common, and people have occasionally spotted space junk burning up in our atmosphere, nobody has yet attempted an intentional artificial shooting star show.

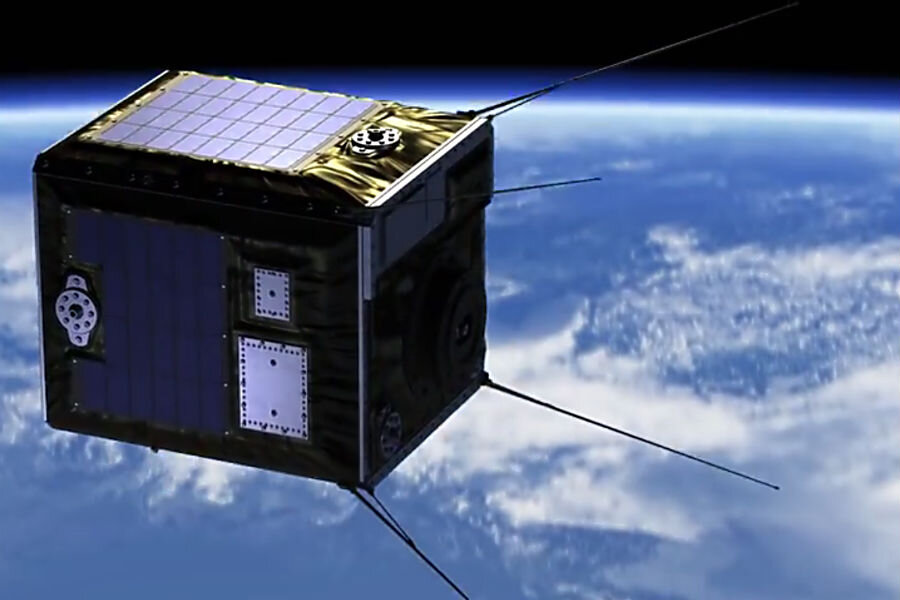

Star-ALE wants to create its Olympic show in more or less the same manner that natural showers occur. The Sky Canvas is designed around a satellite filled with hundreds of “source particles” that the company says will “become ingredients for a shooting star.” The particles would be launched around the world from the spacecraft before entering the atmosphere and beginning to burn at a height of around 40 to 50 miles.

If launched, the Sky Canvas particles would appear slightly dimmer than Sirius, the brightest star observable on Earth, and would be visible even from an urban viewpoint, given a relatively clear night sky. Star-ALE will also cover the particles with various materials that will react with heat to create a palette of colors as the meteors burn through the layers of the atmosphere. The company also noted that its shooting stars will travel slower and farther in the sky than naturally occurring showers, creating a longer-lasting pyrotechnics show than what ordinary meteors can offer.

The spectacle comes with a price tag – each meteor pellet will cost Japan $8,100, while the satellite’s construction and launch will also prove expensive. But Ms. Okajima says she hopes that the production will lead to further developments for Japanese astronomers and scientists.

“[A]stronomy in Japan is supported by large amounts of government assistance. By pouring large amounts of public funds into the creation of enormous equipments, we can aim to fly further into space, and conduct more accurate experiments and observations,” she said.

Tokyo Metropolitan University associate aerospace professor Hironori Sahara told Phys.org that the project could provide insight into environmental change and meteor compsition, as well as set a precedent for the blending of entertainment and experimentation for Japanese researchers.

Star-ALE says it hopes to begin testing the microsatellite’s capabilities outside of a laboratory setting by the end of next year, and that it should be ready for public display in time for Tokyo 2020.